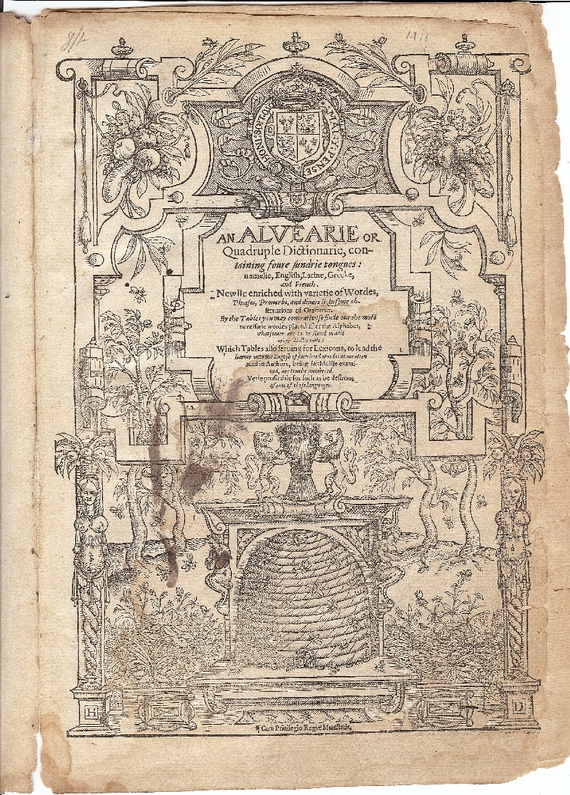

You surely heard plenty about Shakespeare’s birthday yesterday. But did you hear about Shakespeare’s beehive? No, the Bard didn’t moonlight as an apiarist, though in his main line of work as a poet and dramatist he surely had to consult his dictionary fairly often. The question of whether humanity has an identifiable copy of such an illustrious reference volume gets explored in the new book Shakespeare’s Beehive: An Annotated Elizabethan Dictionary Comes to Light by bookseller-scholars George Koppelman and Daniel Wechsler. In their study, they reveal that they may have come into possession of Shakespeare’s very own copy of Baret’s Alvearie, a popular classical quote-laden English-Latin-Greek-French dictionary the man who wrote King Lear would have found “the perfect tool, a honey-combed beehive of possibilities that may not have formed his way of thinking, but certainly fed his appetite and nourished his selection.” He would have, at least, if indeed he owned it. Some solid Shakespeare scholarship points toward his owning a copy of Baret’s Alvearie, but did he own this one, the richly annotated one these guys found on eBay?

Experts haven’t exactly stepped forward in force to back up their claim. Plausible objections include, as Adam Gopnik puts it in a (subscribers-only) New Yorker piece on this Alvearie in particular and humanity’s desire for Shakespearean artifacts in general: “the handwriting just doesn’t look like Shakespeare’s,” “since Shakespeare wrote Elizabethan English, any work of Elizabethan English is going to contain echoes of Shakespeare,” and, of all possible annotators of this particular physical book, Shakespeare “is a prime candidate only because we don’t know the names of all the other bird-loving, inquisitive readers who also liked their dabchicks and their French verbs.” Still, in a striking act of openness, Koppelman and Wechsler have made their — and Shakespeare’s? — Alvearie available for your digital perusal on their site. You have to register as a member first, but then you can draw your own conclusions about Koppelman and Weschler’s discovery — or, as even they call it, their “leap of faith.” Overenthusiastic words, perhaps, but seldom do either successful antiquarian book dealers or dedicated Shakespeare fans lack enthusiasm.

via The Atlantic

Related Content:

Discover What Shakespeare’s Handwriting Looked Like, and How It Solved a Mystery of Authorship

Read All of Shakespeare’s Plays Free Online, Courtesy of the Folger Shakespeare Library

Free Online Shakespeare Courses: Primers on the Bard from Oxford, Harvard, Berkeley & More

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.