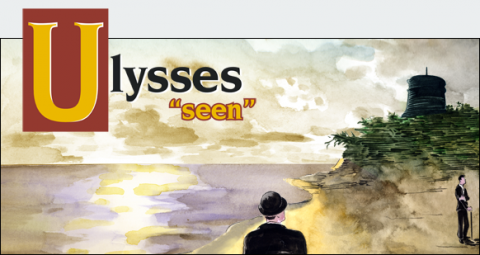

Looking back on the literary career of Leonard Cohen—in full flower in the mid-sixties before his second life as a folk singer/songwriter—one encounters many comparisons to Joyce. For example, in the National Film Board of Canada’s description of Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen, the 1965 documentary film about the 30-year-old Canadian poet, we find: “it truly is, after Joyce, a portrait of the artist as a young man.” On the back cover of Cohen’s second and final novel, the hallucinatory, postmodernist Beautiful Losers, we find a blurb from the Boston Sunday Herald: “James Joyce is not dead…. He lives in Montreal under the name of Cohen.”

Beautiful Losers’ dense system of historical references does put one in mind of Ulysses, but the language, the syntax, the eagle flights into the holy and dives into the profane, remind me somewhat of another Buddhist poet of Canadian extraction, Jack Kerouac. Cohen even sounds a bit like Kerouac, in the short 1967 film, “Poen” (above), an experimental piece that sets four readings of a prose-poem from Beautiful Losers to a montage of starkly provocative images from black-and-white film and photography, Goya, and various surrealists. Made by Josef Reeve for the National Film Board, the short reels out four different recorded takes of Cohen reading the poem. At the end of each reading, he says, “cut,” and the film fades to black.

Taken from the novel’s context, the poem becomes a personal meditation on meditation, or perhaps on writing: “My mind seems to go out on a path, the width of a thread,” begins Cohen and unfolds an image of mental discovery like that described by Donald Barthelme, who once said “writing is a process of dealing with not-knowing…. At best there’s a slender intuition, not much greater than an itch.”

In the animation above, from the NFB’s 1977 “Poets on Film No. 1,” Canadian actor Paul Hecht reads Cohen’s poem “A Kite is a Victim,” from his 1961 collection The Spice-Box of Earth. Like the poem from Beautiful Losers, “A Kite is a Victim” is also about process, but it’s a formal meditation, focused on the image of the kite, which flutters through each of the four stanzas in metaphors of taming, capturing and nurturing language, then letting it go, hoping to be made “worthy and lyric and pure.” The pace of Hecht’s reading, the piano score behind his voice, and the vibrant color of the hand-drawn animation makes this a very different experience of Cohen’s writing than “Poen.”

To see Leonard Cohen reading his poems as a young man, make sure you visit: Young Leonard Cohen Reads His Poetry in 1966 (Before His Days as a Musician Began)

Related Content:

Ladies and Gentlemen… Mr. Leonard Cohen

Street Artist Plays Leonard Cohen’s “Hallelujah” With Crystal Glasses

Leonard Cohen and U2 Perform ‘Tower of Song,’ a Meditation on Aging, Loss & Survival

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him at @jdmagness