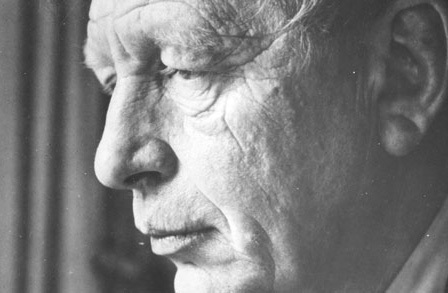

The tech-savviest among us may greet the news of a new BlackBerry phone with an exaggerated yawn, if that. But we have reasons not to dismiss the latest iteration of Research in Motion’s flagship product entirely. The Z10 launched to record early sales in the United Kindgom and Canada. Both the device and the fresh operating system that runs on it “represent a radical reinvention of the BlackBerry,” writes Wall Street Journal personal technology critc Walt Mossberg. “The hardware is decent and the user interface is logical and generally easy to use. I believe it has a chance of getting RIM back into the game.” Even so, building the product amounts to only half the battle; now the BlackBerry brand has to continue gaining, and manage to hold, customer interest. That’s where a certain master of gaining and holding interest named Neil Gaiman comes in.

Say what you will about their phones; Research in Motion’s marketing department has shown an uncommon degree of literary astuteness, at least by the standards of hardware makers. You may remember Douglas Coupland, for instance, turning up in advertisements for the BlackBerry Pearl back in 2006. But the company has recruited Gaiman—the English author of everything from novels like American Gods and Coraline to comic books like The Sandman to television series like Neverwhere to films like MirrorMask—for a more complicated undertaking than Coupland’s. Under the aegis of BlackBerry, Gaiman extends his collaboration-intensive work one domain further. A Calendar of Tales finds him sourcing ideas and visuals from the public in order to create “an amazing calendar showcasing your illustrations beside Neil’s stories.” The short video above recently appeared as the first in a series of episodes covering this storytelling project. Of this we’ll no doubt hear, see, and read much more before 2013’s actual calendar is out.

Related Content:

Download Free Short Stories by Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman Gives Graduates 10 Essential Tips for Working in the Arts

Neil Gaiman Gives Sage Advice to Aspiring Artists

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.