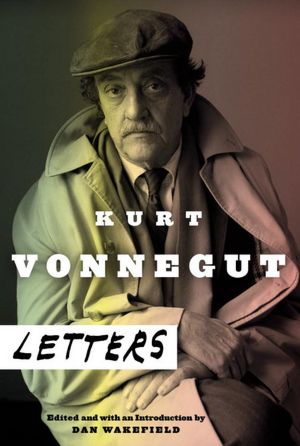

Kurt Vonnegut never did things the conventional way. He didn’t write particularly conventional novels. He certainly didn’t make very conventional speeches at universities. But he did make semi-conventional domestic agreements. Take, for example, this contract written on January 26, 1947. Posted on the Harper’s website in full, this odd little document, dubbed “The Chore List of Champions,” finds Vonnegut outlining all of the tasks he promised to do around the house — this while his young wife, Jane, prepared to give birth to their first child. The contract (the content is conventional, the form is not) will be published in Kurt Vonnegut: Letters next month. And it begins:

Kurt Vonnegut never did things the conventional way. He didn’t write particularly conventional novels. He certainly didn’t make very conventional speeches at universities. But he did make semi-conventional domestic agreements. Take, for example, this contract written on January 26, 1947. Posted on the Harper’s website in full, this odd little document, dubbed “The Chore List of Champions,” finds Vonnegut outlining all of the tasks he promised to do around the house — this while his young wife, Jane, prepared to give birth to their first child. The contract (the content is conventional, the form is not) will be published in Kurt Vonnegut: Letters next month. And it begins:

I, Kurt Vonnegut, Jr., that is, do hereby swear that I will be faithful to the commitments hereunder listed:

I. With the agreement that my wife will not nag, heckle, or otherwise disturb me on the subject, I promise to scrub the bathroom and kitchen floors once a week, on a day and hour of my own choosing. Not only that, but I will do a good and thorough job, and by that she means that I will get under the bathtub, behind the toilet, under the sink, under the icebox, into the corners; and I will pick up and put in some other location whatever movable objects happen to be on said floors at the time so as to get under them too, and not just around them. Furthermore, while I am undertaking these tasks I will refrain from indulging in such remarks as “Shit,” “Goddamn sonofabitch,” and similar vulgarities, as such language is nerve-wracking to have around the house when nothing more drastic is taking place than the facing of Necessity. If I do not live up to this agreement, my wife is to feel free to nag, heckle, and otherwise disturb me until I am driven to scrub the floors anyway—no matter how busy I am.

And then later continues:

g. When smoking I will make every effort to keep the ashtray I am using at the time upon a surface that does not slant, sag, slope, dip, wrinkle, or give way upon the slightest provocation; such surfaces may be understood to include stacks of books precariously mounted on the edge of a chair, the arms of the chair that has arms, and my own knees;

h. I will not put out cigarettes upon the sides of, or throw ashes into, either the red leather wastebasket or the stamp wastebasket that my loving wife made me for Christmas, 1945, as such practice noticeably impairs the beauty and ultimate practicability of said wastebaskets;

j. An exception to the above three-day time limit is the taking out of the garbage, which, as any fool knows, had better not wait that long; I will take out the garbage within three hours after the need for disposal has been pointed out to me by my wife. It would be nice, however, if, upon observing the need for disposal with my own two eyes, I should perform this particular task upon my own initiative, and thus not make it necessary for my wife to bring up a subject that is moderately distasteful to her;

l. The terms of this contract are understood to be binding up until that time after the arrival of our child (to be specified by the doctor) when my wife will once again be in full possession of all her faculties, and able to undertake more arduous pursuits than are now advisable.

You can read the complete “Chore List of Champions” at Harper’s.

via Metafilter

Related Content:

22-Year-Old P.O.W. Kurt Vonnegut Writes Home from World War II: “I’ll Be Damned If It Was Worth It”

Kurt Vonnegut Reads from Slaughterhouse-Five

Kurt Vonnegut’s Eight Tips on How to Write a Good Short Story