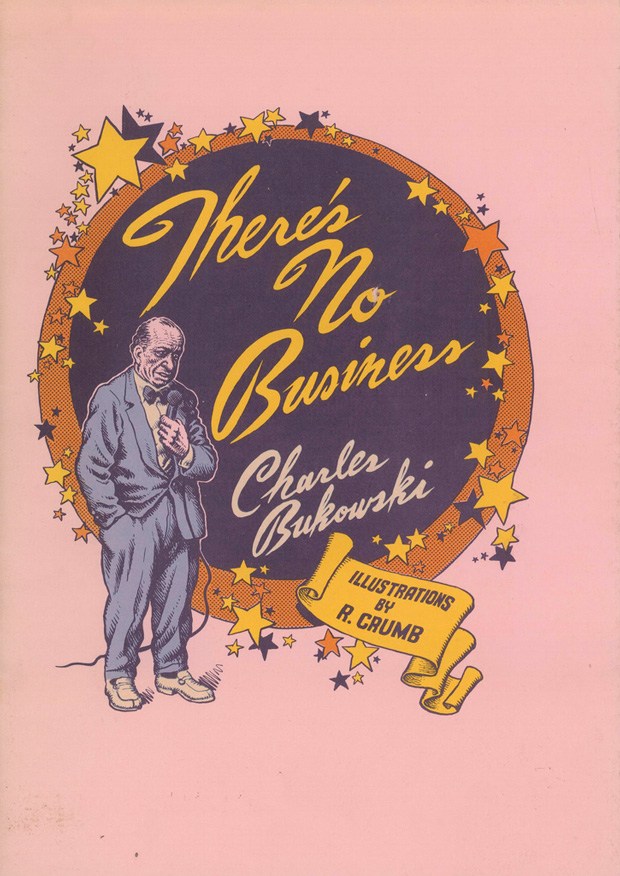

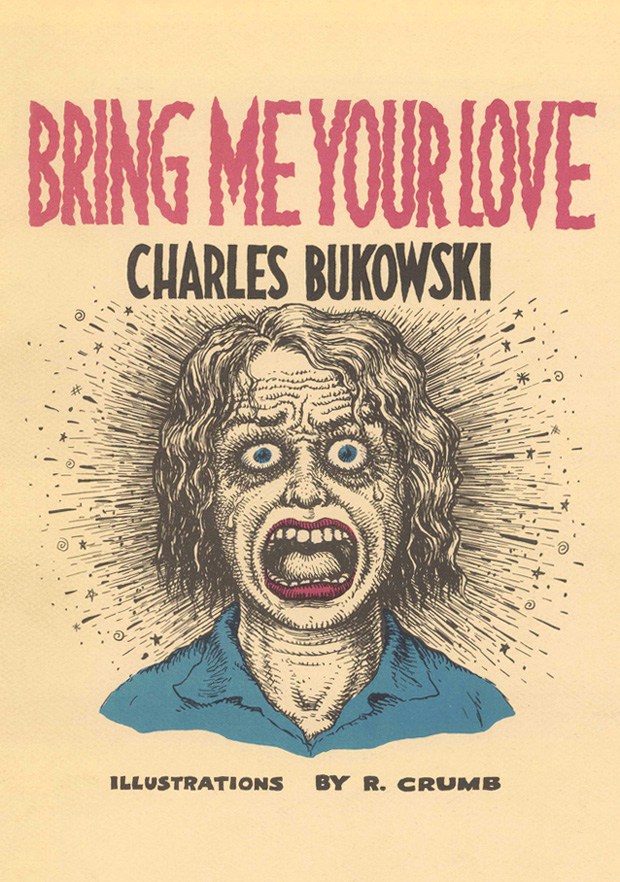

Think of the artists you know who, especially in the 1960s and 70s, portrayed an often sordid reality in detail, just as they saw it, garnering acclaim from enthusiasts, who perceived a high artistry in their seemingly rough-hewn work, and cries from countless detractors who objected to what they saw as the artists’ lazy crudity. In the realm of poetry and prose, Charles Bukowski should come to mind sooner or later; in that of comic art, who fits the bill better than Robert Crumb? It makes only good sense that the work of both men should intersect, and they did in the 1980s when Crumb illustrated two short books by Bukowski, Bring Me Your Love and There’s No Business.

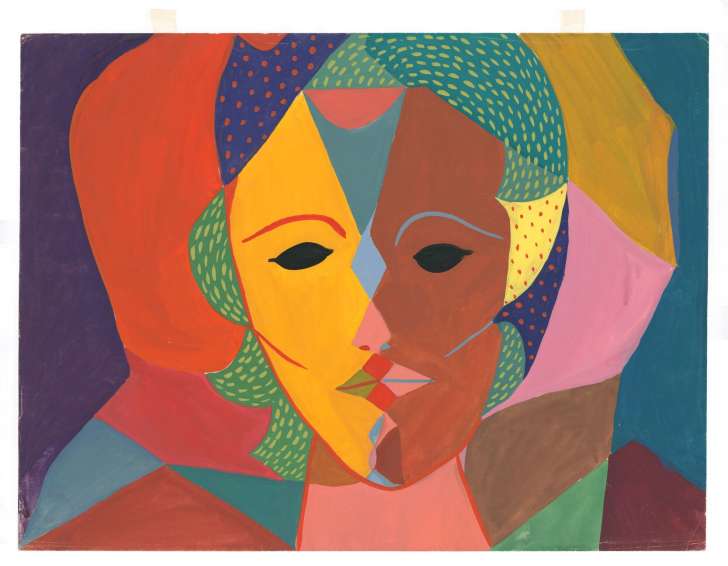

“Crumb’s signature underground comix aesthetic and Bukowski’s commentary on contemporary culture and the human condition by way of his familiar tropes — sex, alcohol, the drudgery of work — coalesce into the kind of fit that makes you wonder why it hadn’t happened sooner,” writes Brain Pickings’ Maria Popova.

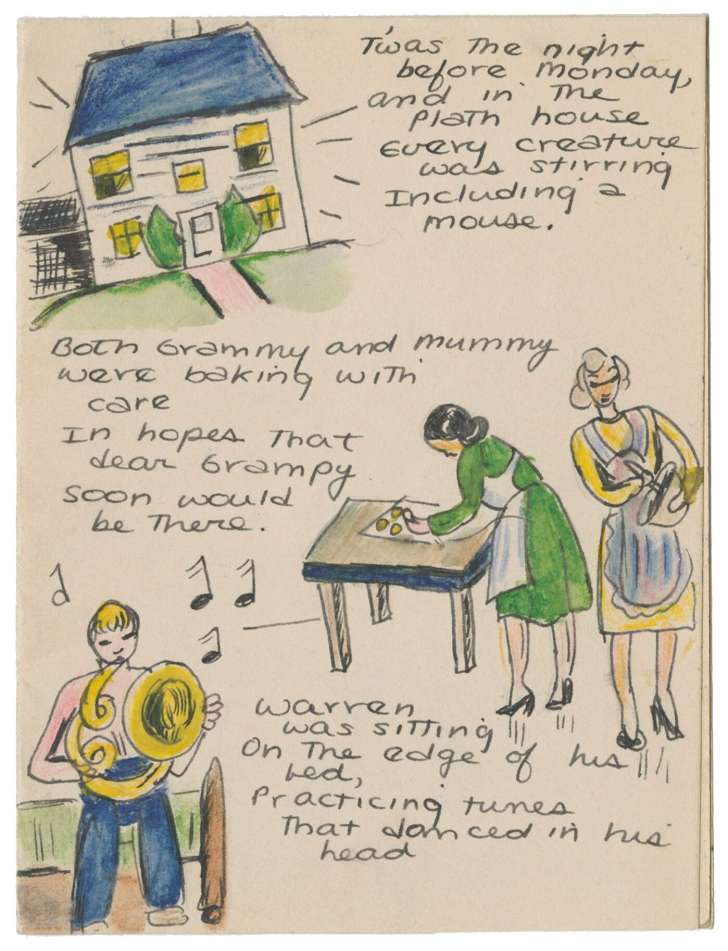

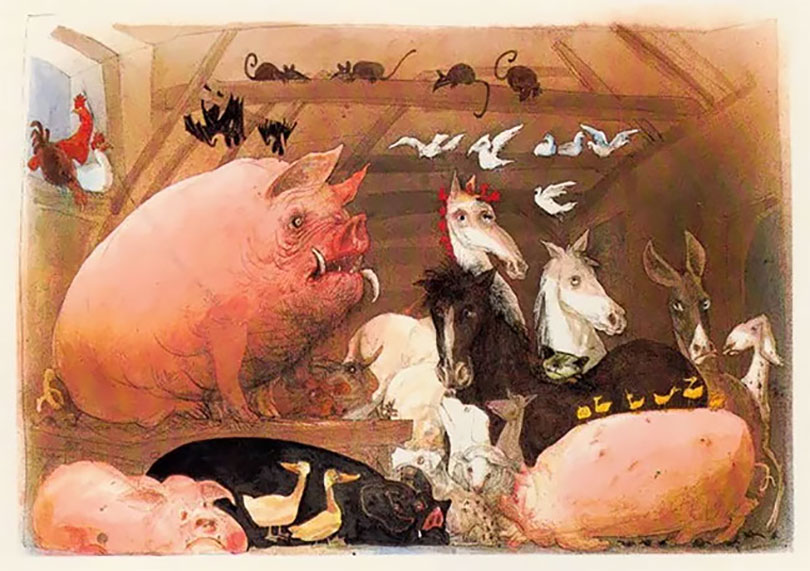

“In 1998, a final posthumous collaboration was released under the title The Captain Is Out to Lunch and the Sailors Have Taken Over the Ship — an illustrated selection from Buk’s previously unpublished diaries, capturing a year in his life shortly before his death in 1994.” As one student of the graphic novel summarizes Bring Me Your Love, “the main character is a man whose personality resembles the main character of most Bukowski stories. He goes through life rather aimlessly, killing time by drinking and having sex. His wife is in a mental hospital.”

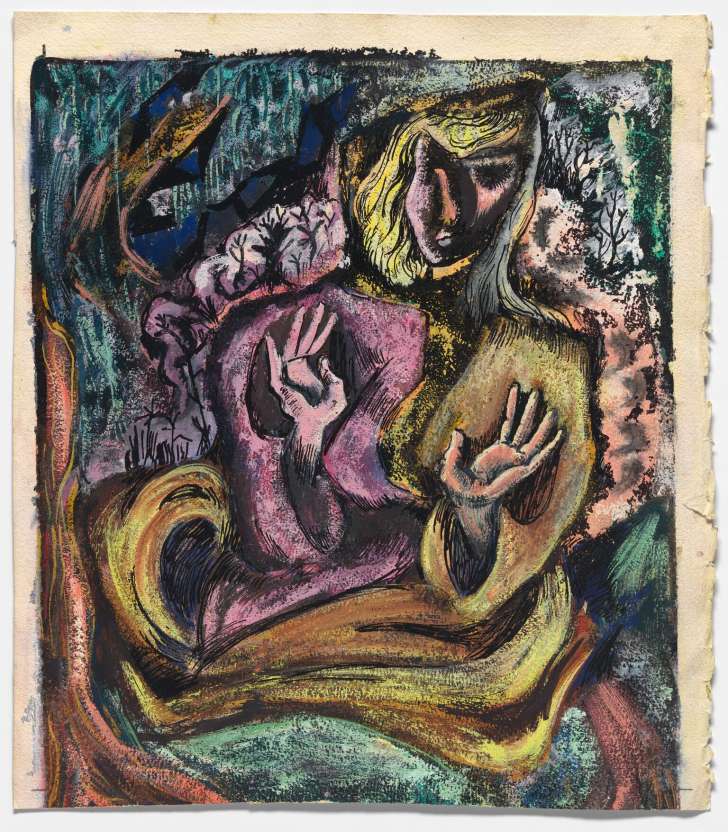

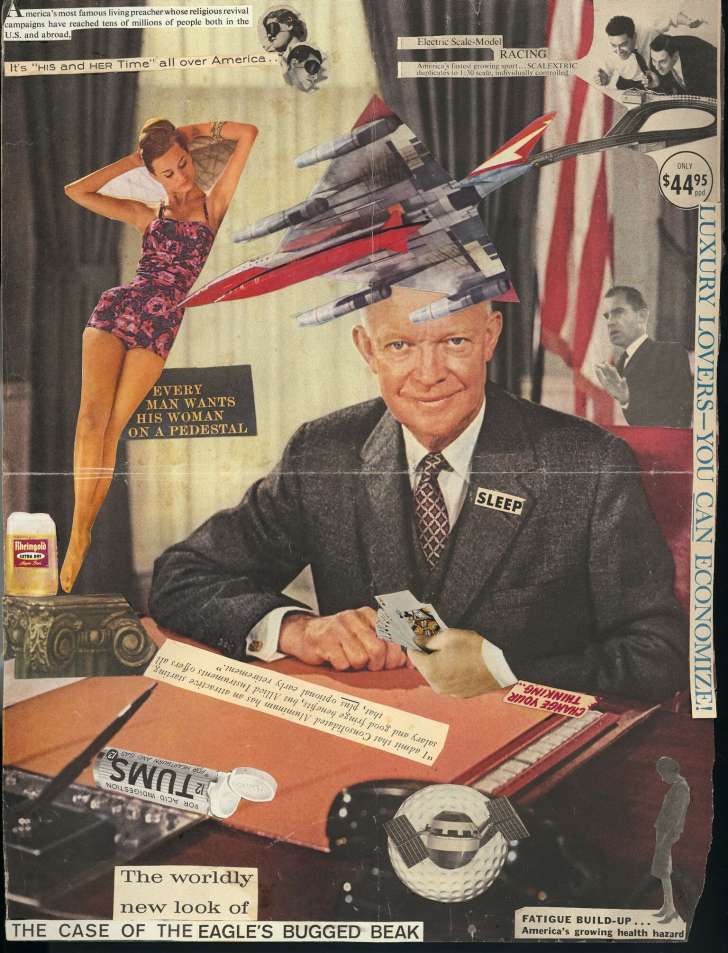

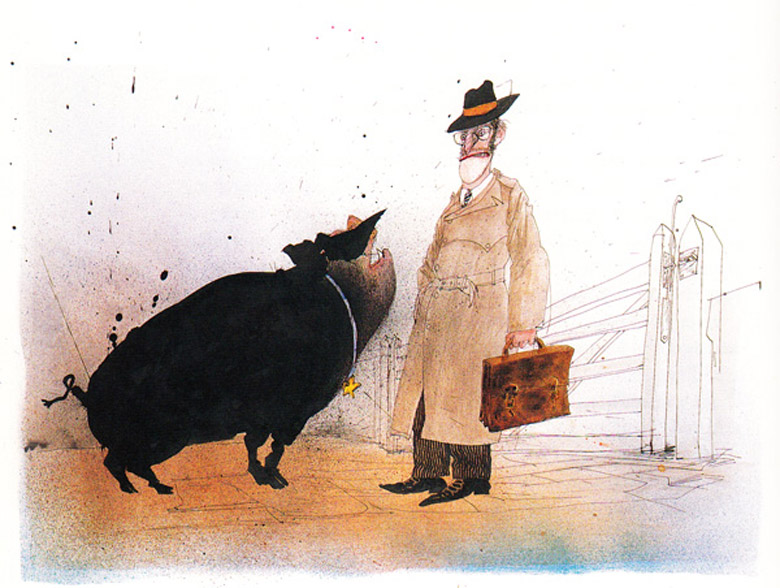

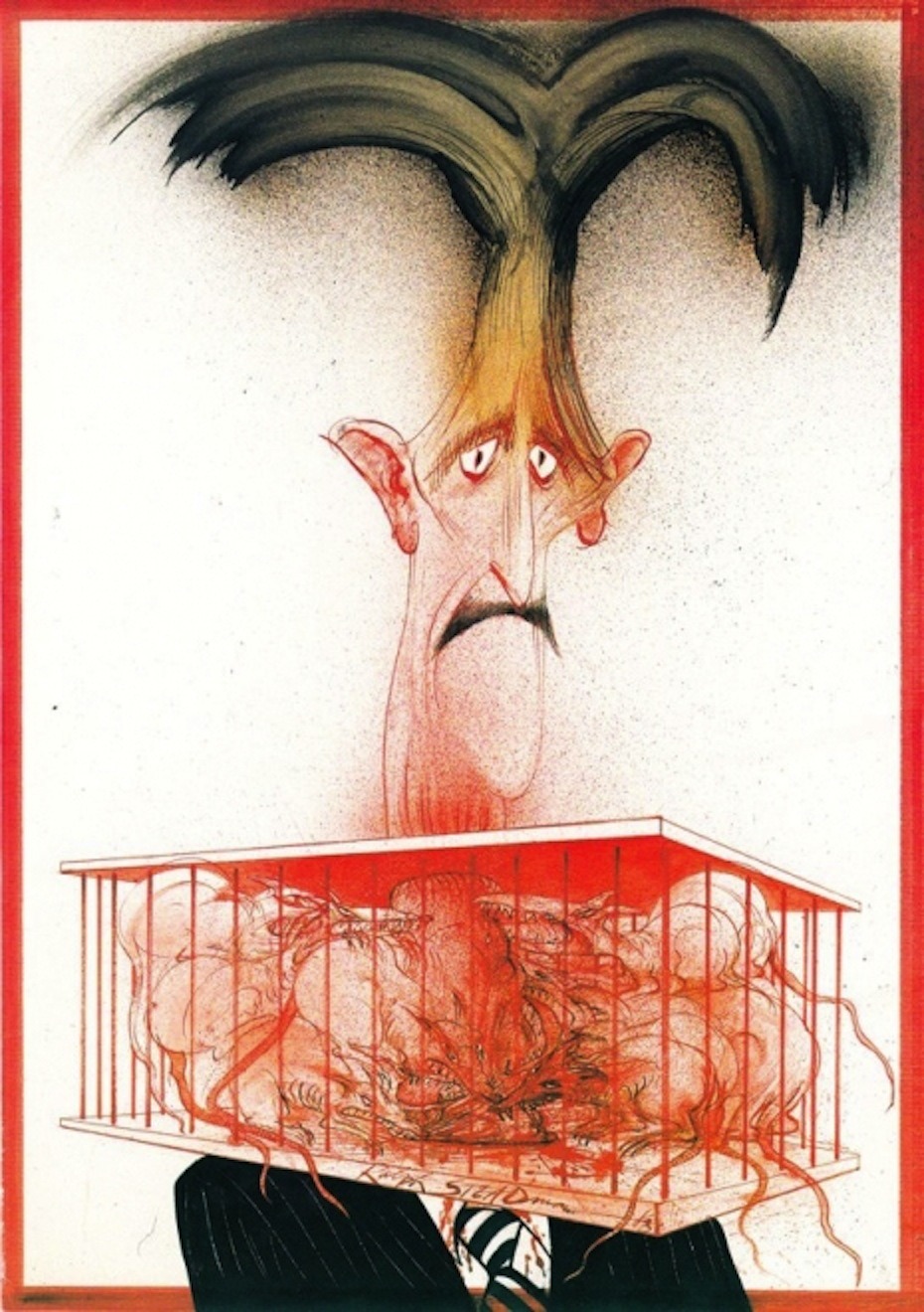

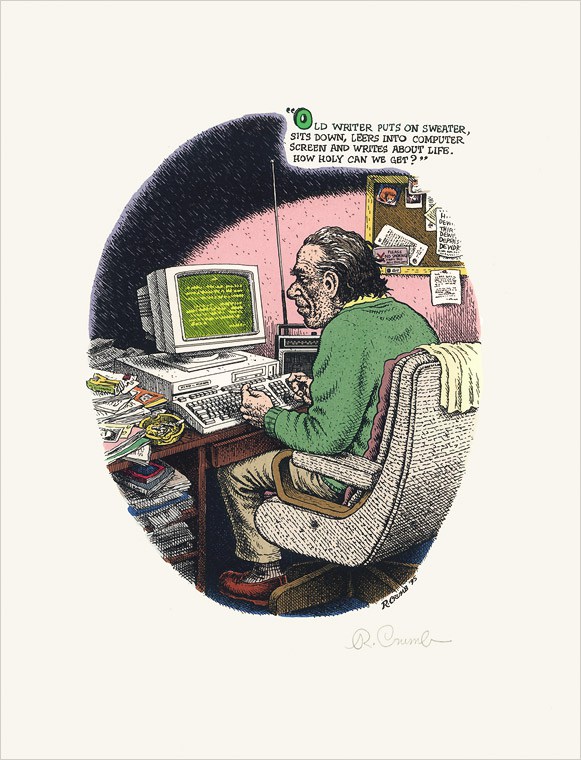

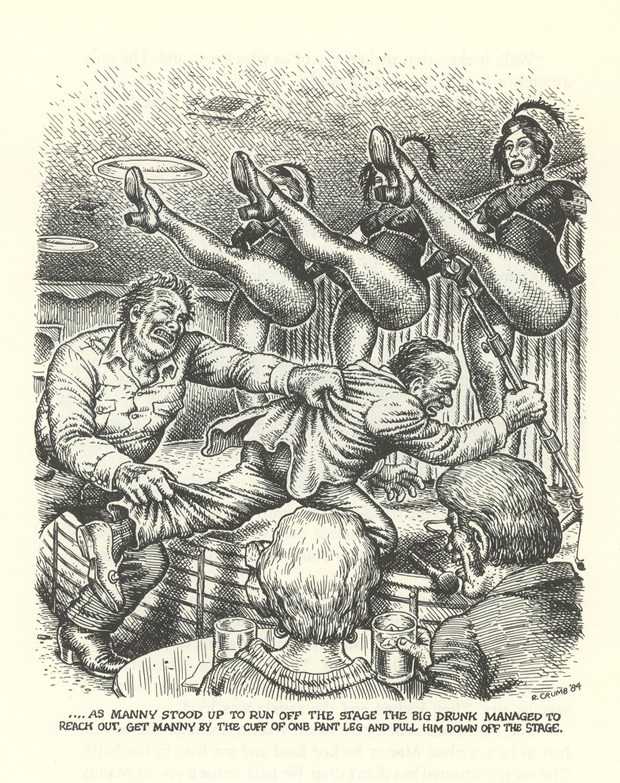

“Crumb’s illustrations give the already gritty storylines a visual context — such as a man who looks much like Buk wrestling on the floor with his ‘wife’ after a dispute involving answering the phone or various barroom skirmishes depicting a Bukowski-looking character running amok,” says Dangerous Minds. “He was a very difficult guy to hang out with in person, but on paper he was great,” Crumb once said of Bukowski, and his illustrations also reveal that he understands Bukowski’s own awareness of the difference between his page self and his real one. “Old writer puts on sweater, sits down, leers into computer screen, and writes about life,” Bukowski writes, in their third and final collaboration, above a Crumb illustration of just such a scene. “How holy can we get?”

See more Crumb illustrations of Bukowski at Brain Pickings.

Related Content:

Four Charles Bukowski Poems Animated

Robert Crumb Illustrates Philip K. Dick’s Infamous, Hallucinatory Meeting with God (1974)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles, the video series The City in Cinema, the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future?, and the Los Angeles Review of Books’ Korea Blog. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.