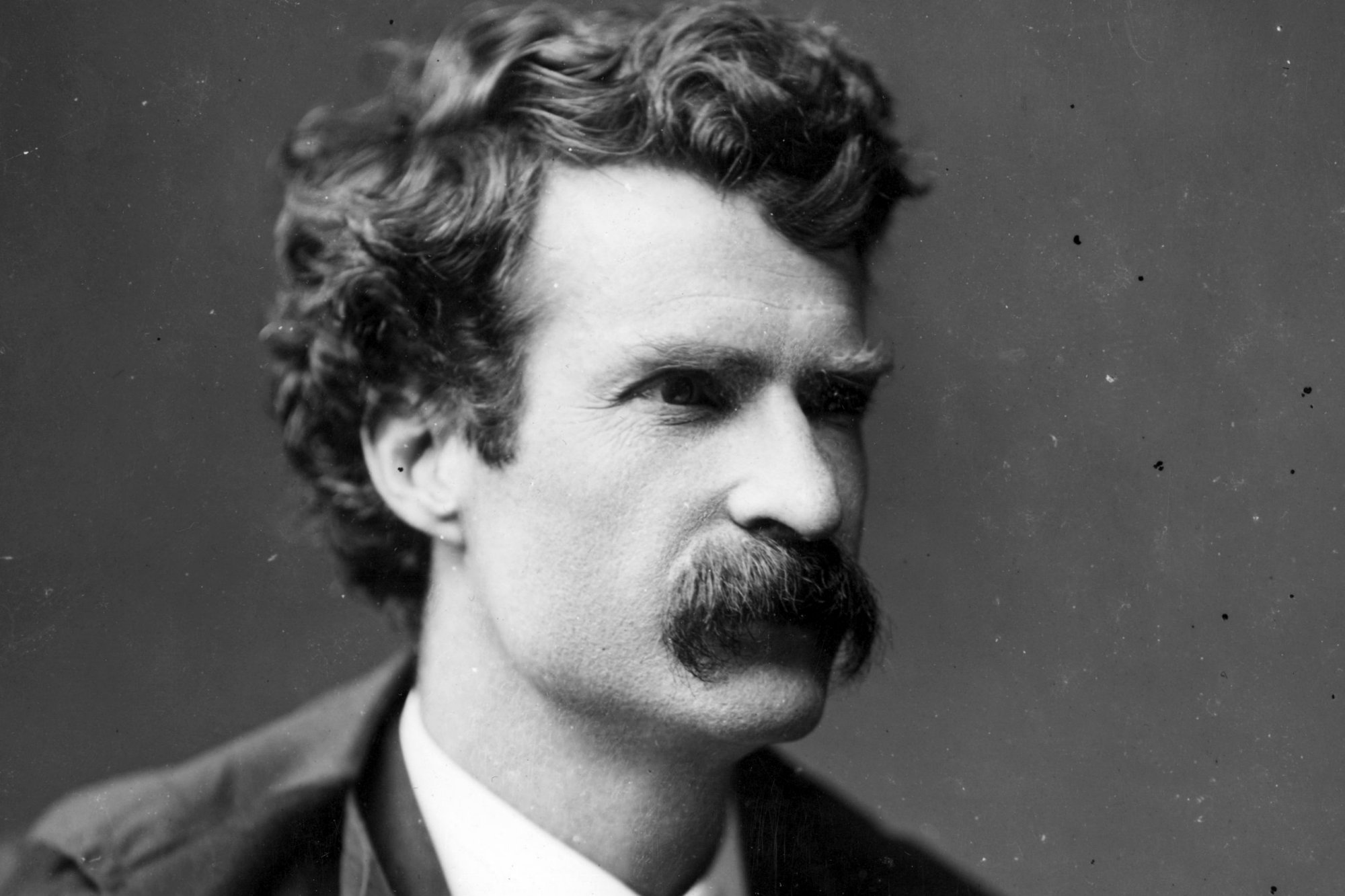

Image by Christiaan Tonnis, via Wikimedia Commons

I don’t have any data, but I think it’s close enough to fact to say that exponentially more people have heard of William S. Burroughs—have even come to revere Burroughs—than have read Burroughs. The phenomenon is unavoidable with a figure as hugely influential throughout the last half of 20th century counterculture. His close association with the Beats; his influence on the 60s through Frank Zappa, The Beatles, and more; his popularity among punks and 70s art rockers and experimentalists; his close affinity with 90s “alternative” bands, Queer writers, and postmodernists; his importance to the druggy rave subcultures of the 90s and oughties…. In almost any creative counterculture you wish to name from the 50s to today, you will find enshrined the name of Burroughs. He was “indeed a man of the 20th Century,” writes Chal Ravens at The Quietus, “he was alive for most of it, after all—and his life and works form the very fabric of the counterculture, seeping into literature, painting, film, theatre and most of all music like a drop of acid on a sugar cube.”

In Burroughs’ case, the life and work are inseparable. His “quixotic and shocking life story should not be dismissed when assessing his legacy,” writes Bearded magazine. That strange life, which did not include writing until he turned 40, “defined him to such a degree that it was many decades before his literary achievements were taken seriously” by the establishment. Nonetheless, in the 50s, “Burroughs opened the doors for sex, drugs, alternative lifestyles and radical politics to be palatable concerns in mainstream culture.” While such themes became palatable through the artists Burroughs influenced, his own writing continues to shock and surprise. Burroughs may have moved in and through so many of the cultures named above, but he was not of them.

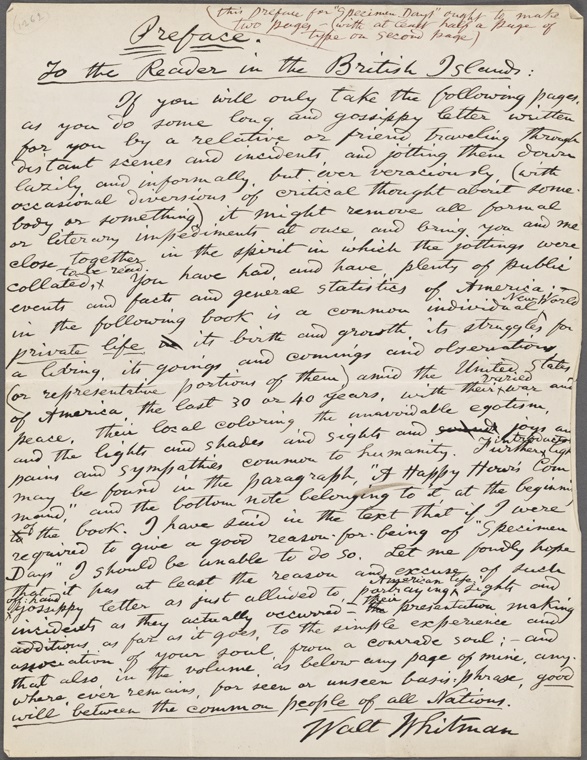

He appeared even to the Beats as a mentor, an “outlaw guru,” and he wrote like a man possessed. Burroughs, The New Yorker remarks, wrote in the “voice of an outlaw reveling in wickedness,” a voice that “bragged of occult power….. He always wrote in tones of spooky authority—a comic effect, given that most of his characters are, in addition to being gaudily depraved, more or less conspicuously insane.” Burroughs in fact described his impulse to write as a kind of insanity or possession. The most outrageous story about him—that he shot his wife Joan Vollmer in Mexico in a supposed William Tell-like stunt—is true. In the introduction to 1985’s Queer, Burroughs confessed:

I am forced to the appalling conclusion that I would never have become a writer but for Joan’s death, and to a realization of the extent to which this event has motivated and formulated my writing. I live with the constant threat of possession, and a constant need to escape from possession, from control. So the death of Joan brought me in contact with the invader, the Ugly Spirit, and maneuvered me into a life long struggle, in which I have had no choice except to write my way out.

Personal obsessions with death, addiction, legal and social control, the occult, and his troubled sexuality drove all of Burroughs’ work—and drove the themes of 20th Century cultural revolt against conformity and conservatism. But though he may have been “a man of the 20th Century,” Burroughs’ most immediate predecessors come largely from the 19th: in decadent poets like Arthur Rimbaud, troubled adventurers like Joseph Conrad, fearless satirists like Ambrose Bierce, and genuine outlaws like Jack Black (who wrote in the 20s of his criminal exploits in the 1880s and 90s). It is in part, perhaps, his transmission of these voices to postwar artists and writers and beyond that granted him such authority. Burroughs’ writing always carried with it the voices of the dead.

Burroughs was obsessed with voices—recorded, cut-up, rearranged; he believed in their power to disrupt, influence, and corrupt. Fittingly, he left us acres of tape of his own ominous monotone: reading his work, offering commentary on technique, spinning bizarre, half-serious conspiracy theories, and distorting literature beyond all recognition through his cut-up technique. Though we all know Burroughs’ name, we can now—no matter our level of familiarity with his writing—become equally familiar with his voice in the playlist above, featuring seven hours of Burroughs recordings from five spoken word albums available on Spotify: The Best of William Burroughs, Spare Ass Annie and Other Tales, Dead City Radio, Break Through in Grey Room, and Call Me Burroughs. (If you don’t already have it, download Spotify here to listen to the playlist.)

Though “we should not underestimate the direct influence of his writing” on counter- and pop culture, Bearded magazine points out (see this list for example), we should also not discount the spooky influence of Burroughs’ haunting recorded voice.

Related Content:

William S. Burroughs Reads Naked Lunch, His Controversial 1959 Novel

William S. Burroughs Teaches a Free Course on Creative Reading and Writing (1979)

How David Bowie, Kurt Cobain & Thom Yorke Write Songs With William Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness