Needless to say, before the development and widespread use of photography in mass publications, illustrations provided the only visual accompaniment to religious texts, novels, books of poetry, scientific studies, and magazines literary, lifestyle, and otherwise. The development of techniques like etching, engraving, and lithography enabled artists and printers to better collaborate on more detailed and colorful plates. But whatever the media, behind each of the millions of illustrations to appear in manuscript and print—before and after Gutenberg—there was an artist. And many of those artists’ names are now well known to us as exemplars of graphic art styles.

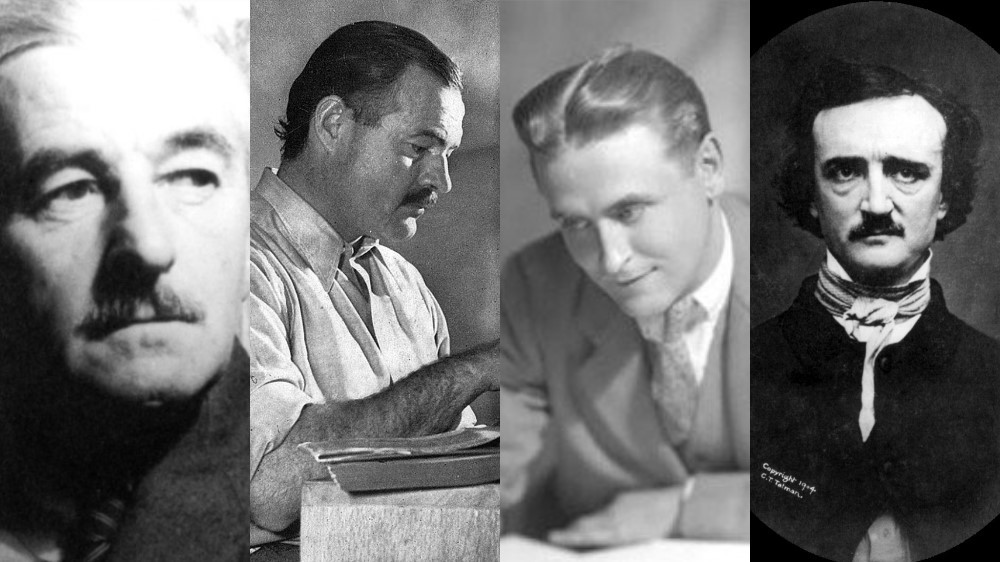

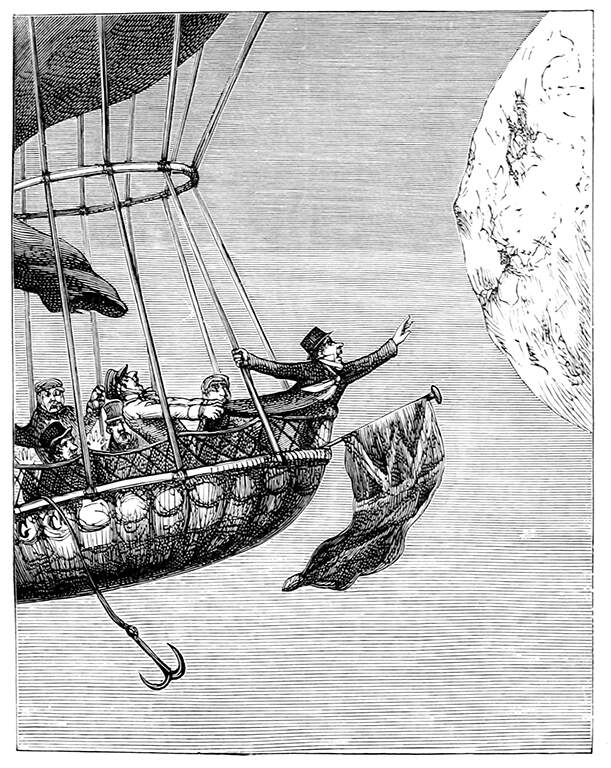

It was in the 19th century that book and magazine illustration began its golden age. Illustrations by artists like George Cruikshank (see his “’Monstre’ Balloon” above”) were so distinctive as to make their creators famous. The hugely influential English satire magazine Punch, founded in 1841, became the first to use the word “cartoon” to mean a humorous illustration, usually accompanied by a humorous caption. The drawings of Punch cartoons were generally more visually sophisticated than the average New Yorker cartoon, but their humor was often as pithy and oblique. And at times, it was narrative, as in the cartoon below by French artist George Du Maurier.

The lengthy caption beneath Du Maurier’s illustration, “Punch’s physiology of courtship,” introduces Edwin, a landscape painter, who “is now persuading Angelina to share with him the honours and profits of his glorious career, proposing they should marry on the proceeds of his first picture, now in progress (and which we have faithfully represented above).” The humor is representative of Punch’s brand, as is the work of Du Maurier, a frequent contributor until his death. You can find much more of Cruikshank and Du Maurier’s work at Old Book Illustrations, a public domain archive of illustrations from artists famous and not-so-famous. You’ll find there many other resources as well, such as biographical essays and a still-expanding online edition of William Savage’s 1832 compendium of printing terminology, A Dictionary of the Art of Printing.

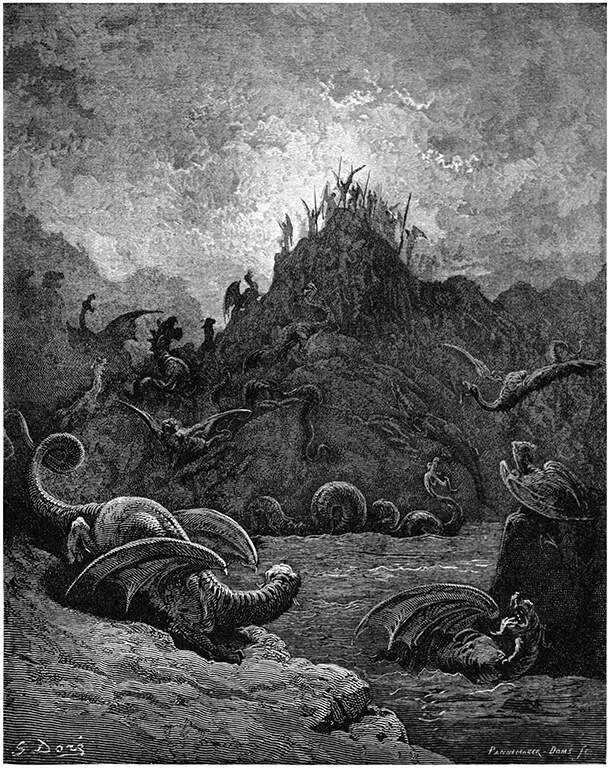

Old Book Illustrations allows you to download high resolution images of its hundreds of featured scans, “though it appears,” writes Boing Boing, “the scans are sometimes worse-for-wear.” Most of the illustrations also “come with lots of details about their original creation and printing.” You’ll find there many illustrations from an artist we’ve featured here several times before, Gustave Doré (see “Gorgons and Hydras” from his Paradise Lost edition, above). As much as artists like Cruikshank and Du Maurier can be said to have dominated the illustration of periodicals in the 19th century, Doré dominated the field of book illustration. In a laudatory biographical essay on the French artist, Elbert Hubbard writes, “He stands alone: he had no predecessors, and he left no successors.” You’ll find a beautifully, and morbidly, 19th century illustrated edition of 17th century poet Francis Quarles’ Emblems, with pages like that below, illustrating “The Body of This Death.”

Not all of the illustrations at Old Book Illustrations date from the Victorian era, though most do. Some of the more striking exceptions come from Arthur Rackham, known primarily as an early 20th century illustrator of fantasies and folk tales. See his “Pas de Deux” below from his edition of The Ingoldsby Legends. These are but a very few of the many hundreds of illustrations available, and not all of them literary or topical (see, for example, the “Science & Technology” category). Be sure also to check out the OBI Scrapbook Blog, a running log of illustrations from other collections and libraries.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Gustave Doré’s Dramatic Illustrations of Dante’s Divine Comedy

An Illustration of Every Page of Herman Melville’s Moby Dick

Harry Clarke’s 1926 Illustrations of Goethe’s Faust: Art That Inspired the Psychedelic 60s

William Blake’s Hallucinatory Illustrations of John Milton’s Paradise Lost

Aubrey Beardsley’s Macabre Illustrations of Edgar Allan Poe’s Short Stories (1894)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness