Images via Wikimedia Commons

Flannery O’Connor’s surgical satire has the ability to strip away the pretensions of not only those characters we are already predisposed to dislike, but also those with whom we may sympathize—that is, educated people with broadly humanist views who think they see right through the self-important prejudices and provincialism of people like Mrs. Hopewell in “Good Country People” or Mrs. Chestny in “Everything that Rises Must Converge.” Both stories dramatize generational tensions in the form of mother/child pairs at odds. In the former, superficial, condescending Mrs. Hopewell and her daughter Joy—a miserable, graduate-educated amputee who prefers to call herself Hulga—battle over their conflicting moral philosophies, only to both be taken in by a devious bumpkin posing as a Bible salesman.

In the latter story—also the title of O’Connor’s most widely read collection, published posthumously in 1965—a mother and son pair present us with two kinds of intolerance. Mrs. Chestny is an overt bigot whose self-importance depends on her sense of herself as a descendent of a proud, if decayed, Southern aristocracy. Julian, her unemployed son, a despairing recent college-grad with designs of becoming a writer but with no real prospects, thinks himself above his mother’s ugly racism and desires nothing more than that she learn her lesson: “The old world is gone,” he says, “You aren’t who you think you are.” When she finally gets her comeuppance at the end of the story (on the way, comically, to a “reducing class”) it may have come, to Julian’s dismay, at the cost of her life. Though we are inclined to sympathize at first with the bitterly ironic son, as the story progresses, the narrator reveals his motivations as hardly more elevated than his mother’s hate and fear.

These are not characters we fall in love with, but we never forget them either. Through them we come to see that none of us is who we think we are, that the human capacity for self-deception is boundless. This is the lesson common to each of O’Connor’s stories, one she offers anew with wit and variety each time, and each time through a kind of revelation. Her stories draw us into points of view that reveal themselves—through sudden epiphanies and gradual unfoldings—to be inadequate, deluded, profoundly limited. And though O’Connor’s Southern Catholic pessimism has astonishingly universal reach, the regional grounding of her stories and novels present us with particularly American versions of the petty meanness and conceit common to the human species.

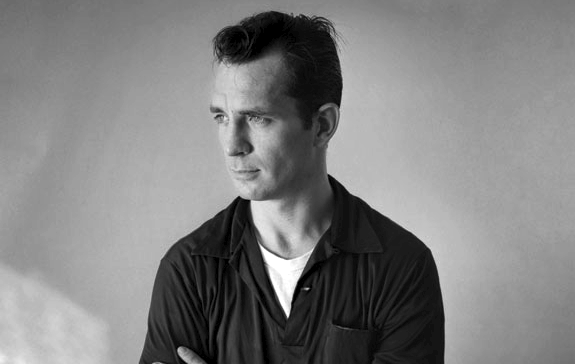

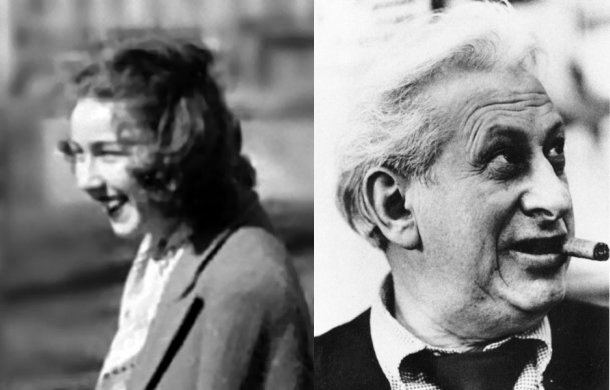

In “Revelation,” another story from Everything Rises Must Converge—read above by Studs Terkel—O’Connor lays bare some particularly American race and class biases in the character of Mrs. Turpin, another older Southern lady whose prejudices are more vicious and spiteful than both Mrs. Hopewell and Mrs. Chestny put together. The story achieves a subtle examination of some very unsubtle attitudes, and the reading by Terkel, in his Chicago-accented radio voice, does it justice indeed. Terkel read the story on his radio show, The Studs Terkel Program, in 1965, the year of its publication and a little over a year after O’Connor’s death. See a complete transcript of the broadcast at the Terkel show’s Pop Up Archive. The audio above has been kindly enhanced for us by sound designer Berrak Nil.

As an added treat, hear “Everything that Rises Must Converge” read above by Academy Award-winning actress Estelle Parsons, who became known in her later years for playing an overbearing mother like the story’s Mrs. Chestny in the TV sitcom Roseanne. Despite the quaintness of O’Connor’s characterizations, we are not far at all from the world she depicted, given the stubborn persistence of human bigotry, selfishness, and blind self-regard. For more classic O’Connor, hear the sharp-tongued writer, who died too soon of complications from her lupus at age 39, read her story “A Good Man is Hard to Find” here.

The reading above can be found in our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

Studs Terkel Interviews Bob Dylan, Shel Silverstein, Maya Angelou & More in New Audio Trove

Rare 1959 Audio: Flannery O’Connor Reads ‘A Good Man is Hard to Find’

Flannery O’Connor’s Satirical Cartoons: 1942–1945

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness