As a lover of fantasy and science fiction, but by no means a know-it-all fanboy, I know what it’s like to come to a fictional universe late. It can seem like everyone else has already read the canon, seen the movies, and memorized the genealogies, origin stories, magical arcana, number of ancient blood feuds, etc. For example, I grew up steeped in Star Trek but never watched Dr. Who. Now that British sci-fi show is seemingly everywhere, and I find myself intrigued. But who has the time to catch up on several decades of missed episodes? Some people may have felt similarly in the last few years about The Lord of the Rings, what with the number of J.R.R. Tolkien adaptations besieging theaters. If you haven’t read any of those books, Middle Earth—for all its air of medieval legend and Norse myth—can be a very confusing place.

Thanks to Peter Jackson’s films, for better or worse, Tolkien’s books have even more cultural currency than they did in the 70s, when Led Zeppelin mined them for lyrical inspiration, and “Frodo lives” graffiti appeared on overpasses everywhere.

This brings us to the videos we feature here. Presented in a rapid fire style like that of motormouth YA novelist and video educator John Green, “The Lord of the Rings Mythology Explained” is exactly that–two very quick tours, with illustrations, through the complex mythological world of Middle Earth, the setting of The Lord of the Rings trilogy, The Hobbit, and other books you’ve maybe never heard of. These videos were made before the final installment of Jackson’s interminable Hobbit trilogy, but they cover most major developments before and after the events in short book on which he based those films.

I’ll say this for the effort—Tolkien’s world is one I thought I knew, but I didn’t know it nearly as well as I thought. Like most people, frankly, I haven’t read the sourcebook of so much of that world’s genesis, The Silmarillion, which gets a survey in the first video at the top of the post. I’m much more familiar, and you may be as well—through books or films—with the mythologies of The Lord of the Rings trilogy proper, covered in the video above. If these two thorough explainers don’t satisfy your curiosity, you can likely have further questions answered at one of the videos’ sources, Ask Middle Earth, a site that solicits “any question about Middle Earth.” Another source, the work of comparative mythologist Verlyn Flieger, who specializes in Tolkien, also promises to be highly illuminating.

Related Content:

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

“The Tolkien Professor” Presents Three Free Courses on The Lord of the Rings

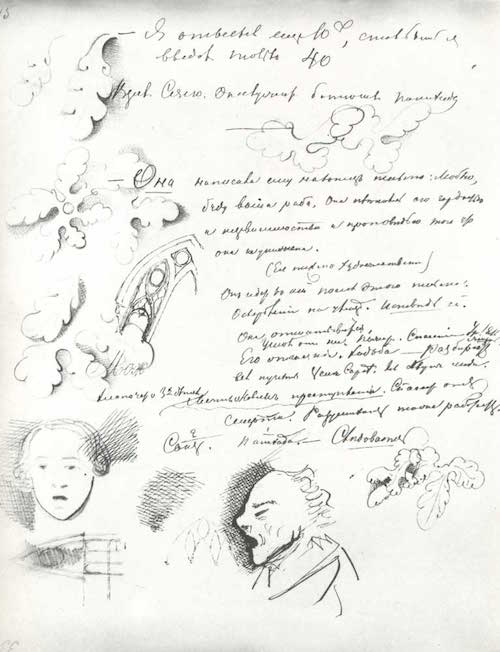

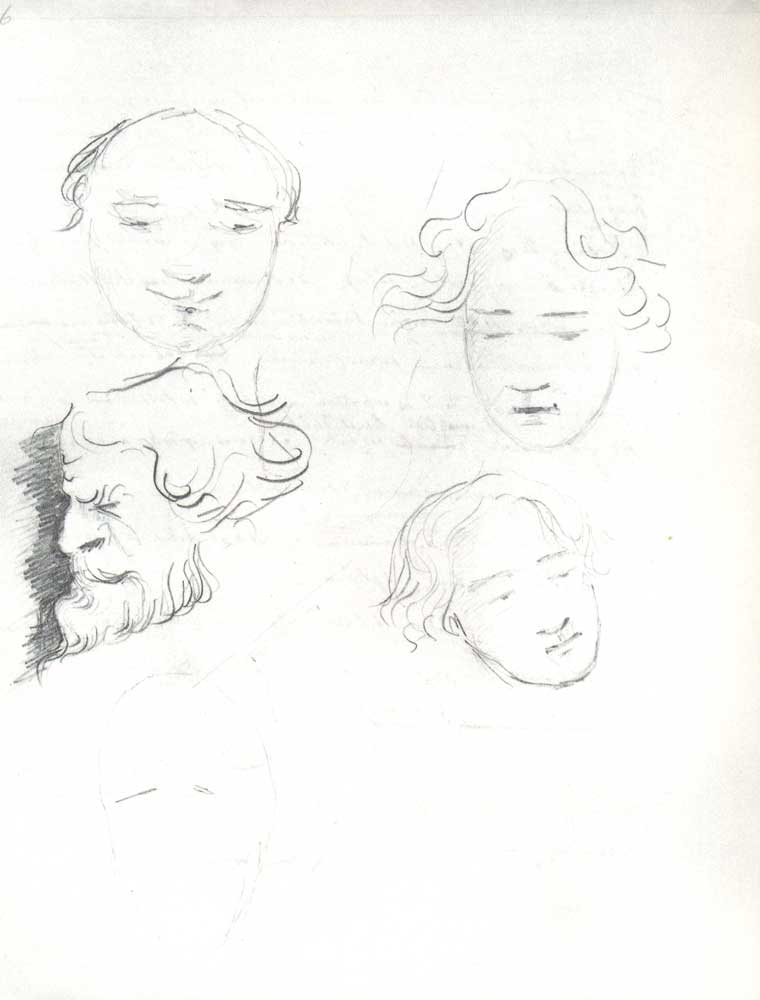

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

J.R.R. Tolkien Snubs a German Publisher Asking for Proof of His “Aryan Descent” (1938)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness