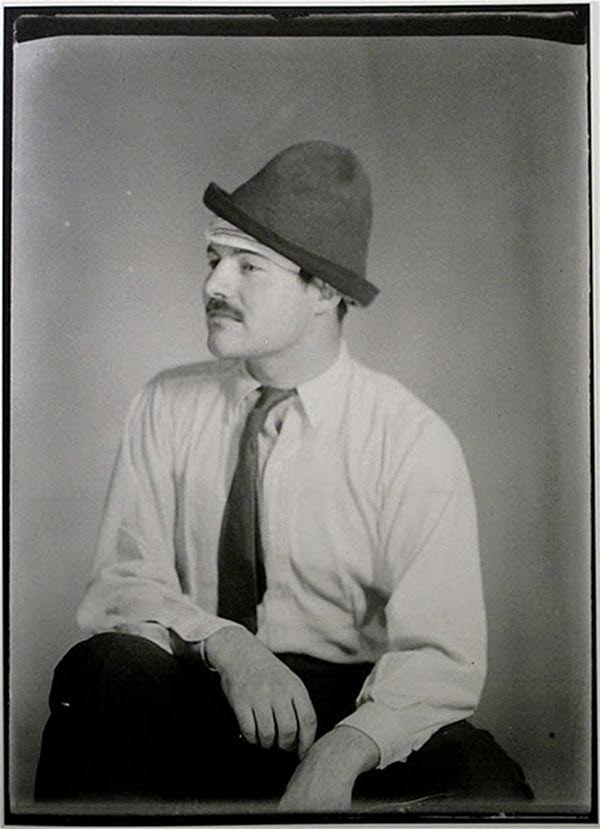

When photographers specialize in portraits of famous people, they often speak of finding a visual way to reveal their oft-photographed subject’s rarely exposed nature; to bring their depths, in other words, to the surface. Man Ray (1890–1976), the Surrealist photographer and artist, had his own way of doing most everything, and he certainly had his own approach to celebrity portraiture. Take, for example, his 1923 shot of Ernest Hemingway above, taken just a couple years after both the writer and photographer joined the moveable feast of Paris, which Man Ray would call home for most of his career.

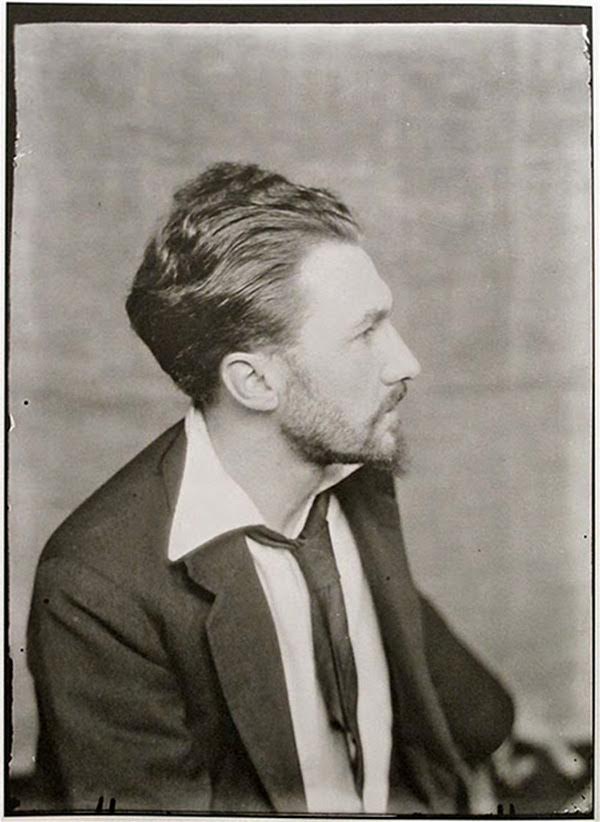

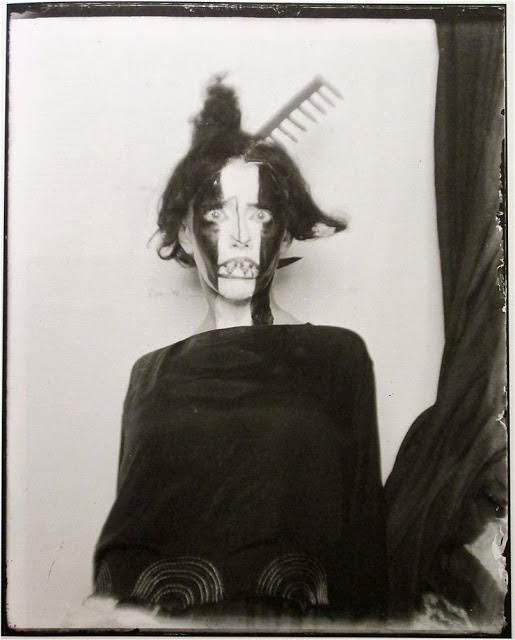

That same year and in that same urban bohemia, Man Ray photographed another famed man of letters, the modernist poet Ezra Pound. You can see the somewhat more conventional-looking result of that encounter just above. Below, we have a far less conventional-looking portrait from 1922, which takes as its subject the dancer Bronislava Nijinska, who perhaps only counts as famous to you if you know the history of 20th-century ballet — but I say anyone willing to appear in a portrait looking that frightening has earned all the fame they can get.

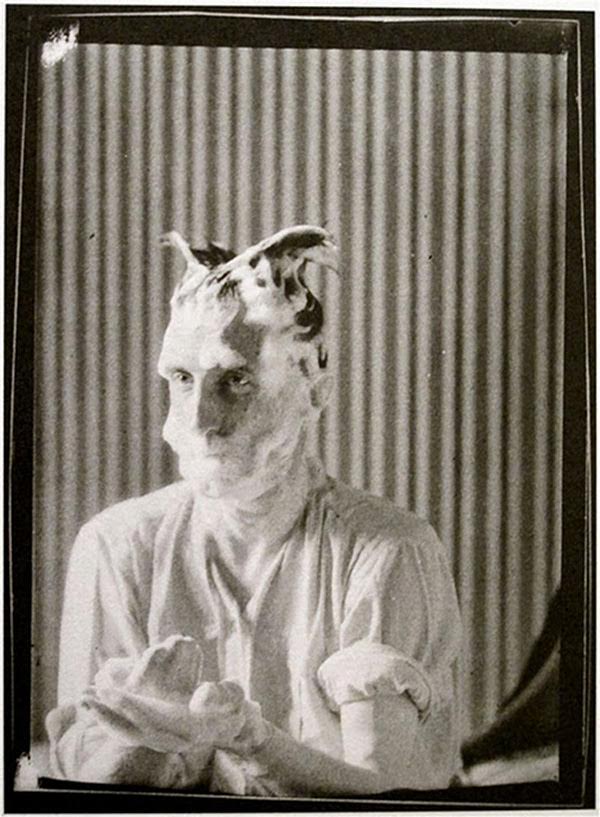

Marcel Duchamp, who appears below, sat for Man Ray in 1921 looking less scary than silly, but as one of the wittiest and most artistically forward-thinking figures of the era, he surely got the joke. These appear in the book Man Ray: Paris — Hollywood — Paris, which collects 500 of the portraits Man Ray left in his archives when he died in 1976, all of “members of Dadaist and Surrealist circles, of artists and painters, of writers and US emigrants of the Lost Generation, of aristocrats, and paragons of the worlds of fashion and theater.”

You can sample more such works, which capture as only Man Ray would the natures of such icons as André Breton, Salvador Dalí, and Lee Miller, at Mondo Blogo. You can also find many more works, in general, by Man Ray on the MoMA’s website.

via Flavorwire

Related Content:

Three Essential Dadaist Films: Groundbreaking Works by Hans Richter, Man Ray & Marcel Duchamp

Philosopher Portraits: Famous Philosophers Painted in the Style of Influential Artists

Coffee Portraits of John Lennon, Albert Einstein, Marilyn Monroe & Other Icons

Colin Marshall writes elsewhere on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.