The successes of the Freedman’s Bureau, initiated by Abraham Lincoln in 1865 and first administered under Oliver Howard’s War Department, are all the more remarkable considering the intense popular and political opposition to the agency. Under Lincoln’s successor, impeached Southern Democrat Andrew Johnson, the Bureau at times became a hostile entity to the very people it was meant to aid and protect—the formerly enslaved, especially, but also poor whites devastated by the war. After years of defunding, understaffing, and violent insurgency the Freedman’s Bureau was officially dissolved in 1872.

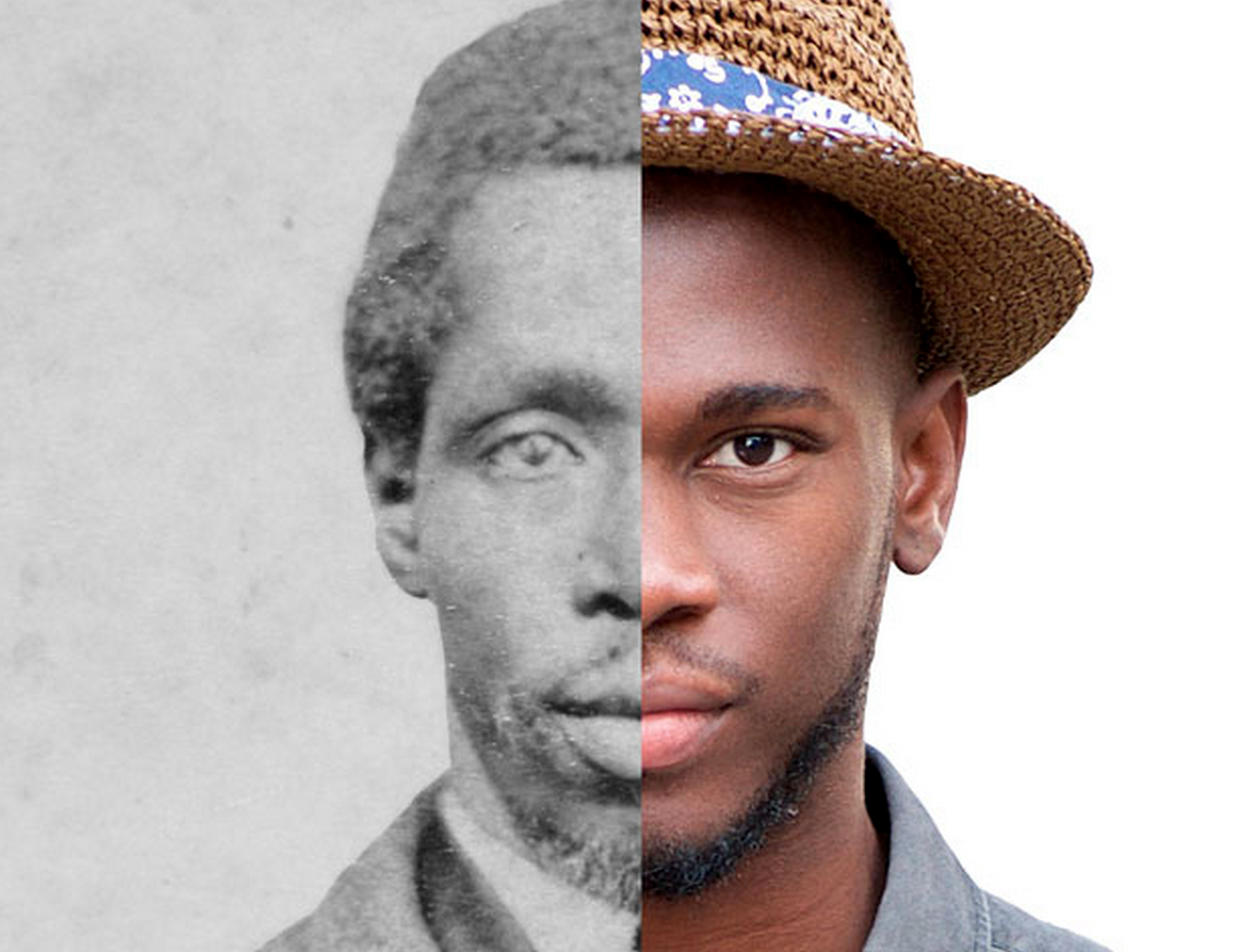

In those first few years after emancipation, however, the Bureau built several hospitals and over a thousand rural schools in the South, established the Historically Black College and University system, and “created millions of records,” notes the National Museum of African American History and Culture (NMAAHC), “that contain the names of hundreds of thousands of formerly enslaved individuals and Southern white refugees.” Those records have enabled historians to reconstruct the lives of people who might otherwise have disappeared from the record and helped genealogists trace family connections that might have been irrevocably broken.

As we noted back in 2015, those records have become part of a digitization project named for the Bureau and spearheaded by the Smithsonian, the National Archives, the Afro-American Historical and Genealogical Society, and the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter Day Saints, whose FamilySearch is the largest genealogy organization in the world. “Using modern, digital and web-based technology and the power of [over 25,000!] volunteers,” says Hollis Gentry, a genealogical specialist at the NMAAHC, the Freedman’s Bureau Project “is unlocking information from a transformative era in the history of African American families and the American nation.”

That information is now available to the general public, “globally via the web” here, as of June 20th, 2016, allowing “all of us to enlarge our understanding of the past.” More specifically, the Freedman’s Bureau Project and FamilySearch allows African Americans to recover their family history in a database that now includes “the names of nearly 1.8 million men, women and children” recorded by Freedman’s Bureau workers and entered by Freedman’s Bureau Project volunteers 150 years later. This incredible database will give millions of people descended from both former slaves and white Civil War refugees the ability to find their ancestors.

There’s still more work to be done. In collaboration with the NMAAHC, the Smithsonian Transcription Center is currently relying on volunteers to transcribe all of the digital scans provided by FamilySearch. “When completed, the papers will be keyword searchable. This joint effort will help increase access to the Freedmen’s Bureau collection and help the public learn more about the United States in the Reconstruction Era,” a critical time in U.S. history that is woefully underrepresented or deliberately whitewashed in textbooks and curricula.

“The records left by the Freedmen’s Bureau through its work between 1865 and 1872 constitute the richest and most extensive documentary source available for investigating the African American experience in the post-Civil War and Reconstruction eras,” writes the National Archives. Soon, all of those documents will be publicly available for everyone to read. For now, those with roots in the U.S. South can search the Freedman’s Bureau Project database to discover more about their family heritage and history.

And while the Smithsonian’s transcription project is underway, those who want to learn more can visit the Freedman’s Bureau Online, which has transcribed hundreds of documents, including labor records, narratives of “outrages committed on freedmen,” and marriage registers.

Related Content:

Visualizing Slavery: The Map Abraham Lincoln Spent Hours Studying During the Civil War

The Civil War and Reconstruction: A Free Course

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness