One can only tolerate so many educational videos in self-isolation before the brain begins to rebel.

Hands-on learning. That’s what we’re craving.

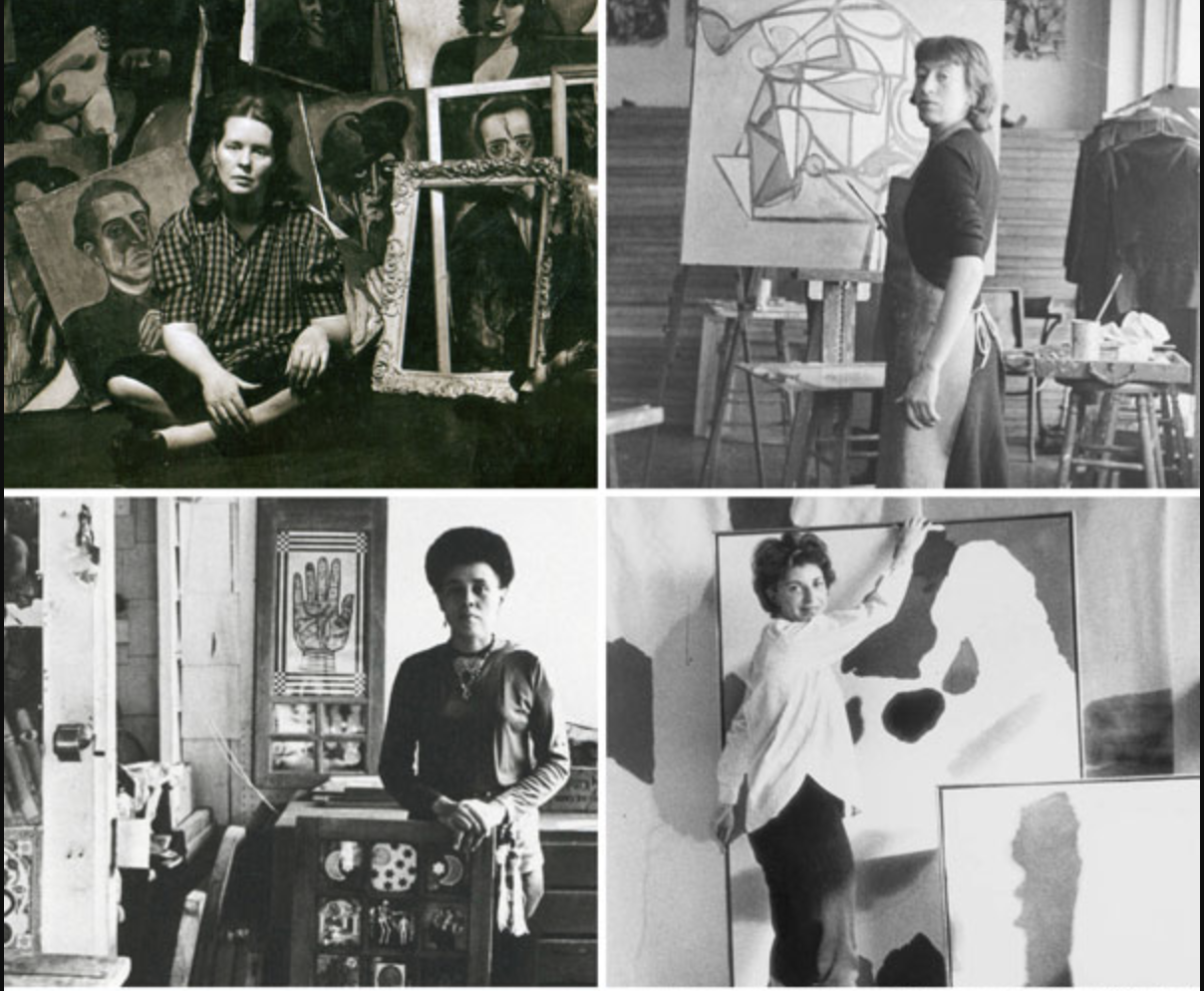

And ultimately, that’s what the Getty provides with an addictive challenge to captive audiences on Twitter, Facebook, and Instagram to re-create iconic artworks using three household objects.

Participants are encouraged to look at the Getty’s downloadable, digitized collection and beyond for a piece that speaks to them, possibly because of their ability to match it by dint of hair color, physique or perfect prop.)

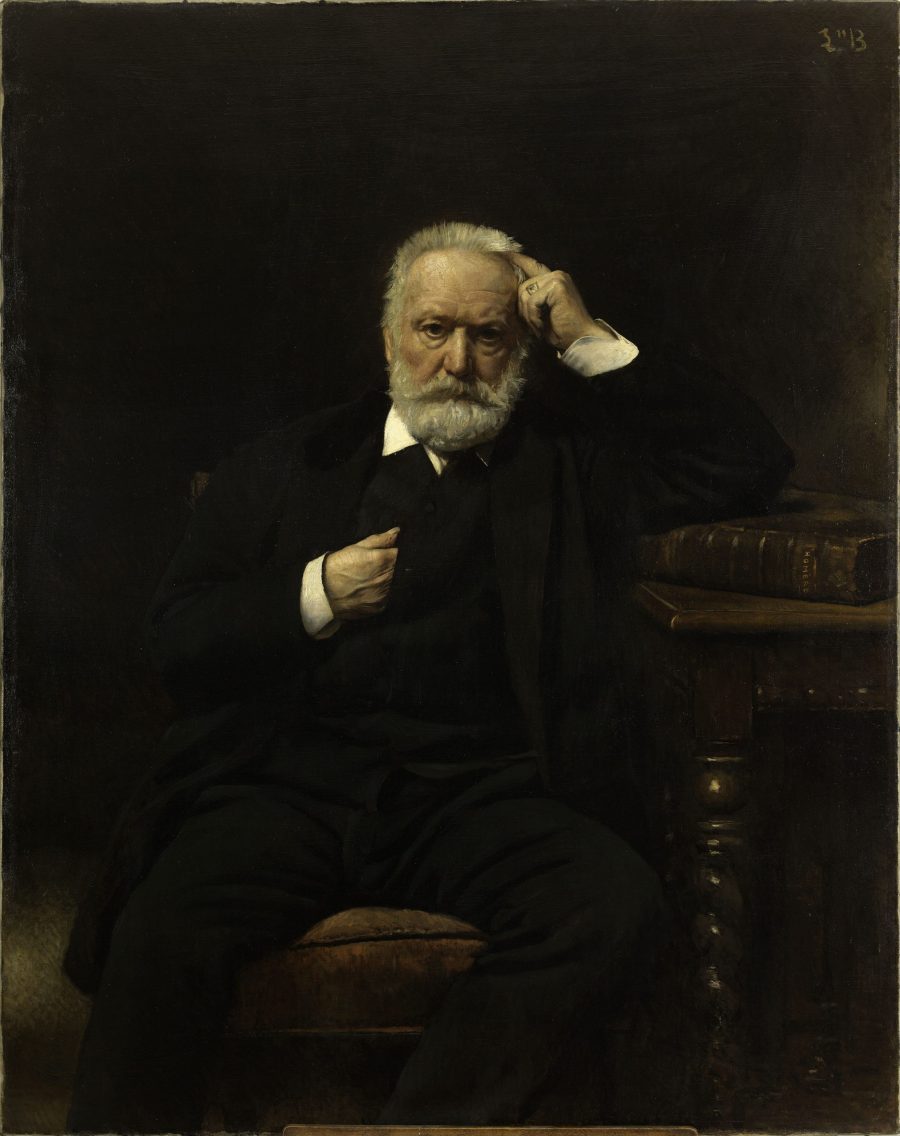

Certain works quickly emerged as favorites, with Johannes Vermeer’s Girl with a Pearl Earring (c. 1665) the clear front runner.

The Mauritshuis, where Girl with a Pearl Earring is quarantined, along with other Hague-dwellers such as Rembrandt’s The Anatomy Lesson of Dr Nicolaes Tulp and Fabritius’ The Goldfinch, describes it thusly:

Girl with a Pearl Earring is Vermeer’s most famous painting. It is not a portrait, but a ‘tronie’ – a painting of an imaginary figure. Tronies depict a certain type or character; in this case a girl in exotic dress, wearing an oriental turban and an improbably large pearl in her ear.

Johannes Vermeer was the master of light. This is shown here in the softness of the girl’s face and the glimmers of light on her moist lips. And of course, the shining pearl.

Let’s have a look, shall we?

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Vermeer’s extraordinary application of light and shadow is a tall order for most amateurs, but it’s wonderful to see how much careful consideration has been given to the original subject’s expression, the cant of her head, the arrangement of her garments.

It seems the best way to study a work of art is to become that work of art… especially when one is trapped at home, seeking distraction, and forced to improvise with available objects.

Let us pray we’ll be set loose long before Halloween, but also that the challenge takers won’t forget how ingenious, easily sourced, and cost-effective their costumes were: a pillowcase, a button, an inverted party dress, the hem of a sibling’s blue t‑shirt, rescued from the rag bag still smelling faintly of vinegar from pre-coronavirus household cleaning.

That off-the-rack “sexy cat” won’t stand a chance.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

No one’s disqualified if the number of items used in service of these recreations exceeds the originally stiuplated 3. As long as the participants are having (educational!) fun, this is one of those challenges where everybody wins… especially the baby, the dog, the guy with the mustache and the lady with the turkey on her head, even though the baby and the guy with the mustache forgot their earrings.

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

View this post on Instagram

Some tips for participants accompany a handful of memorable entries on the Getty’s behind-the-scenes blog, The Iris. We’ve got links to a number of world class museums’ and libraries’ digital collections here and can’t wait to see what you come up with.

Meanwhile, enjoy even more recreations by searching for #gettychallenge or having a look at the Instagram of Tussen Kunst & Quarantaine, whose attempt to conjure Girl With A Pearl Earring using a placemat, a towel and a garlic bulb, launched the project that prompted the Getty and the Rijksmuseum to follow suit.

Extra points if you accept the #neckruffchallenge inspired by our history-loving artist friend, Tyler Gunther’s take on the #gettychallenge, below.

View this post on Instagram

Related Content:

Flashmob Recreates Rembrandt’s “The Night Watch” in a Dutch Shopping Mall

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. She has been crowdsourcing art in isolation, most recently a hastily assembled tribute to the classic 60s social line dance, The Madison. Follow her @AyunHalliday.