As the mourning period for David Bowie continues this week, for which I am very much taking part (my favorite Bowie is the Berlin trilogy Bowie in case you’re interested), the Internet continues through its own stages of grief. First brief news stories and anecdotes from fellow artists, then long think-pieces (some very good), then to best-of lists, and now to interesting ephemera.

For an artist who saw both sides of commercial success, Bowie’s television commercial appearances number less than a dozen over his life. Part of that comes from his mastery and control over his image–he knew when to go out, and when to stay in, to get things done, you might say–and part may come from his early history behind the scenes where the commercial sausage gets made.

In 1963, Bowie left school to go work at Nevin D. Hirst Advertising on London’s Bond Street, where he worked as a storyboard artist for about a year, a job he took to please his father. Although he was dismissive of that time doing his 9‑to‑5, it was later clear to friends, band mates, and biographers that he had picked up a lot from advertising–how to package himself, how to manipulate feeling, the power of image and words.

Jump forward to 1967 and a long haired Davy Jones makes one of his earliest appearances in this ice cream ad for Luv “The Pop Ice Cream,” directed by another up-and-comer, Ridley Scott, who had recently made his first short film, “A Boy and a Bicycle.” It’s groovy, but, as Luv’s not around any more, apparently didn’t move enough units.

And then Davy Jones turns into Major Tom and the ‘70s belonged to him. He finally agrees in 1980 to do a commercial, but only in Japan. In this minimal ad for Crystal Jun Rock Sake, Bowie looks beautiful, handsome, and sleek, right at the height of his sophisticated Lodger-era glamour. He plays a piano, gazes at a post-modern Mt. Fuji, and utters one word: “Crystal.” Bowie wrote the music, an outtake from the Lodger sessions, and it was released as a single in Japan, and a b‑side in the West. Bowie commented that “the money is a useful thing” for doing ads like this, out of sight from the West.

The next time Bowie appears is in 1983, calling out for Americans to demand their MTV in a series of rotoscoped and colorized ads near the dawn of the network. (This is a badly edited compilation of Bowie’s spots).

If Bowie had yet to “sell out” it was only four years later, during the Glass Spider Tour, that he did, with this re-worded, re-recorded version of “Modern Love,” duetting with Tina Turner. At the time it felt like the end of a career that had turned Bowie into an overly coiffed parody of himself. In retrospect, if you can look past the soda, it’s a cute commercial, with the star looking a bit like “Blinded by Science”-era Thomas Dolby.

Then more silence and, by the time Bowie reappears in 2001, it is literally as the man who falls to earth in an ad for XM satellite radio. (Bowie made yet another appearance in an XM ad in 2005.)

In 2004, he appears again, shilling Vittel water. Here Bowie’s in full career retrospective mode, making peace with his chameleon self and appreciating it all. Set to the Reality track “Never Get Old” (our dear wish that was not to be), it features Bowie tribute performer David Brighton trying on every outfit from the Starman’s crowded wardrobe in a house filled with incarnations.

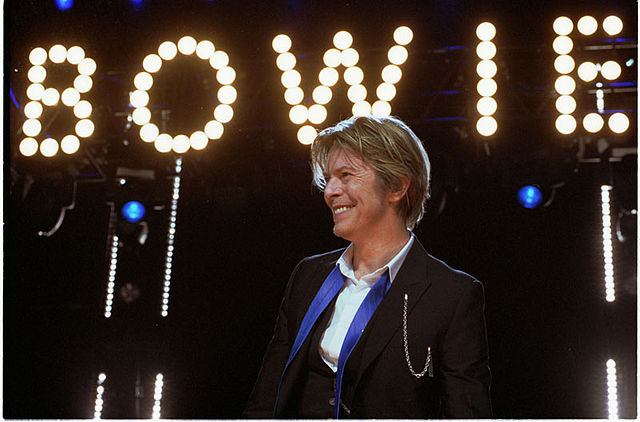

That leaves us with his final television ad appearance in 2013, seen at the top of this post, still looking fit, and performing a baroque version of The Next Day track “I’d Rather Be High” for a Venetian ball-set ad for Louis Vuitton. Fitting to go out surrounded by beauty and glamor, but check those lyrics:

I stumble to the graveyard and I

Lay down by my parents, whisper

Just remember duckies

Everybody gets got

Related Content:

How David Bowie, Kurt Cobain & Thom Yorke Write Songs With William Burroughs’ Cut-Up Technique

David Bowie Paper Dolls Recreate Some of the Style Icon’s Most Famous Looks

The Making of Queen and David Bowie’s 1981 Hit “Under Pressure”: Demos, Studio Sessions & More

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.