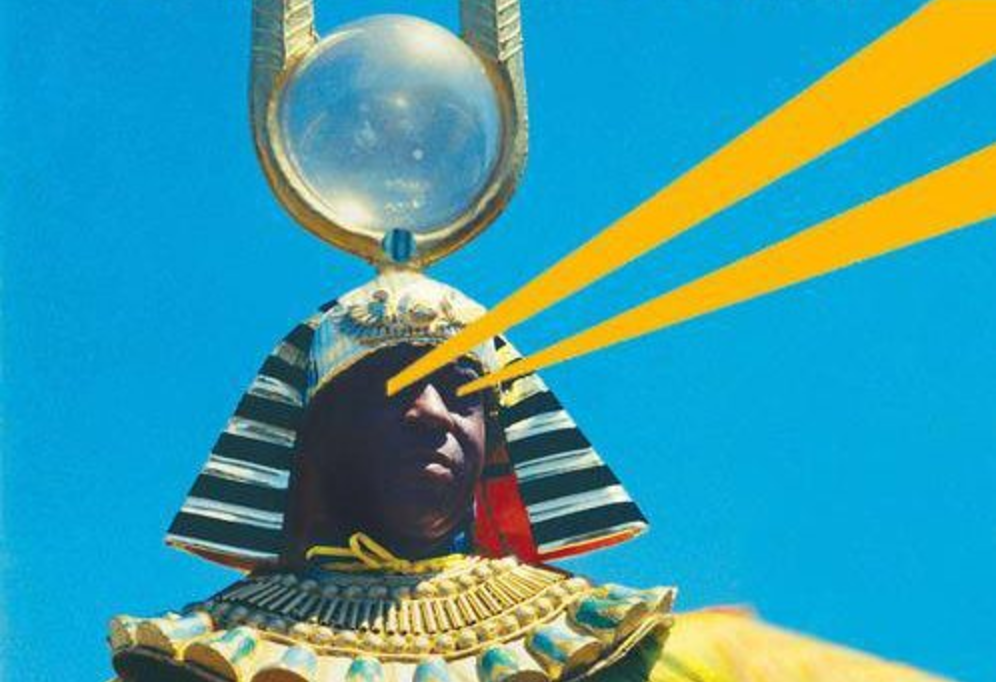

On a recent road trip through the Deep South, I made a pilgrimage to several sacred shrines of American music, including obligatory stops in Memphis at the garish Graceland and unassuming Sun Studios. But the highlight of the tour had to be that city’s Stax Museum of American Soul Music (“nothing against the Louvre, but you can’t dance to Da Vinci”). Housed in a re-creation of the original Stax Records, the museum mainly consists of aisles of glass cases, in which sit instruments, costumes, and other memorabilia from artists like Booker T. and the MGs, Sam & Dave, The Staples Singers, and Isaac Hayes. One particular relic caught my attention for its radiating aura of authenticity—a battered first pressing of James Brown’s 1956 “Please, Please, Please,” the song that built the house of Brown and his backing singer/dancers the Famous Flames—a song, wrote Philip Gourevitch, that “doesn’t tell a story so much as express a condition.”

“Please, Please, Please” was not a Stax release, but the museum rightly claims it as a seminal “precursor to soul.” Brown bequeathed to sixties soul much more than his over-the-top impassioned delivery—he brought to increasingly kinetic R&B music a theatricality and showmanship that dozens of artists would strive to emulate. But no group could work a stage like Brown and his band, with their machine-like precision breakdowns and elaborate dance routines. And while it seems like Chadwick Boseman does an admirable impression of the Godfather of Soul in the upcoming Brown biopic Get on Up, there’s no substitute for the real thing, nor will there ever be another. By 1964, Brown and the Flames had worked for almost a decade to hone their act, especially the centerpiece rendition of “Please, Please, Please.” And in the ’64 performance above at the T.A.M.I.—or Teenage Awards Music International—at the Santa Monica Civic Auditorium, you can see Brown and crew for the first time do the so-called “cape act” (around 7:50) during that signature number. David Remnick describes it in his New Yorker piece on this performance:

…in the midst of his own self-induced hysteria, his fit of longing and desire, he drops to his knees, seemingly unable to go on any longer, at the point of collapse, or worse. His backup singers, the Flames, move near, tenderly, as if to revive him, and an offstage aide, Danny Ray, comes on, draping a cape over the great man’s shoulders. Over and over again, Brown recovers, throws off the cape, defies his near-death collapse, goes back into the song, back into the dance, this absolute abandonment to passion.

It’s an act Brown distilled from both charismatic Baptist church services and professional wrestling, and it’s a hell of a performance, one he pulled out, with all his other shimmying, strutting, moonwalking stops, in order to best the night’s lineup of big names like the Beach Boys, Chuck Berry, Marvin Gaye, the Supremes, and the Rolling Stones, who had the misfortune of having to follow Brown’s act. Keith Richards later called it the biggest mistake of their career. You can see why. Though the Stones put on a decent show (below), next to Brown and the Flames, writes Remnick, they looked bland and compromising—“Unitarians making nice.”

via The New Yorker

Related Content:

Every Appearance James Brown Ever Made On Soul Train. So Nice, So Nice!

James Brown Saves Boston After MLK’s Assassination, Calls for Peace Across America (1968)

James Brown Gives You Dancing Lessons: From The Funky Chicken to The Boogaloo

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness