When I first entered college in the mid-‘90s, the phenomenon of pop culture studies in academia seemed like an exciting novelty, bound to the ethos of the Clinton years. Often incisive, occasionally frivolous, pop culture studies made academia fun again, and reinvigorated the world of scholarly publishing and college life in general. All manner of fandom ruled the day: we took classes in hip hop videos and Buffy the Vampire Slayer, Alanis Morrissette redefined irony, and nearly everyone got hired right after graduation (see for reference the cult classic 1994 film PCU). These days I don’t need to tell you that the prospects for new grads are considerably reduced, but I’m very happy to find academic societies and journals still organized around TV shows, fantasy novels, and pop music. Today we bring you two examples from the world of Classic Rock & Roll Studies (to coin a term). First up we have BOSS, or “The Biannual Online-Journal of Springsteen Studies.”

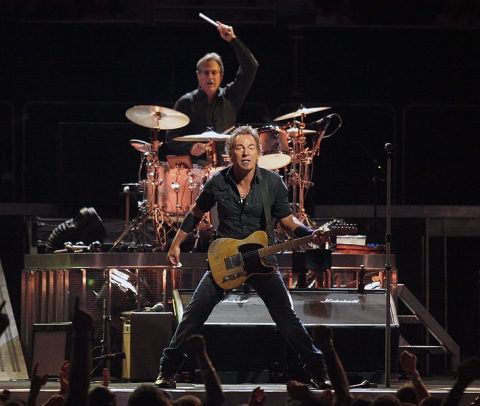

Springsteen Studies is not new. In fact, a massive Springsteen symposium called “Glory Days”—jointly sponsored by Virginia Tech, Penn State, and Monmouth University—has taken place twice in West Long Branch, New Jersey since 2005 and is currently preparing for its next event. BOSS, however, only just emerged, the first scholarly Springsteen journal ever published. The first issue will appear in June of this year, and the editors are now soliciting 15 to 25 page academic articles for their January, 2015 issue. Describing themselves as a “scholarly space for Springsteen Studies in the contemporary academy,” BOSS seeks “broad interdisciplinary and cross-disciplinary approaches to Springsteen’s songwriting, performance, and fan community.” Springsteen scholars: check the BOSS site for deadlines and contact info.

Unlike most scholarly journals, BOSS is open-access, so fans and admirers of all kinds can read the sure-to-be fascinating discussions it fosters as it works toward securing “a place for Springsteen Studies in the contemporary academy.” Springsteen Studies’ advocacy appears to be working—Rutgers University plans to add a Springsteen theology class, covering Springsteen’s entire discography, and other institutions like Princeton and the University of Rochester have offered Springsteen courses in the past.

In another first for a specialized pop culture field, the first-ever academic conference on the work of Pink Floyd will be held this coming April 13 at Princeton University. Called “Pink Floyd: Sound, Sight, and Structure,” the event promises to be a multi-media extravaganza, featuring as its keynote speaker Grammy-award winning Pink Floyd producer and engineer James Guthrie. (See Guthrie and others discuss the production of the surround-sound Super Audio CD of Wish You Were Here in the video above). In addition to Guthrie’s talk, and his surround sound mix of the band’s music, the conference will offer “live compositions and arrangements inspired by Pink Floyd’s music,” an “exhibition of Pink Floyd covers and art,” and a screening of The Wall. Papers include “The Visual Music of Pink Floyd,” “Space and Repetition in David Gilmour’s Guitar Solos,” and “Several Species of Small Furry Animals: The Genius of Early Floyd.” Admission is free, but you’ll need to RSVP to get in. The town of Princeton will join in the festivities with “Outside the Wall,” a series of events and specials on drinks, dining, art, and music.

While these events and publications may seem to locate pop culture studies squarely in New Jersey, those interested can find conferences all over the world, in fact. A good place to start is the site of the PCA (“Pop Culture Association”), which hosts its annual conference next month in Chicago, and the International Conference on Media and Popular Culture will be held this May in Vienna. Pop culture and media studies still seem to me to be particular products of the optimistic ‘90s (due to my own vintage, no doubt), but it appears these academic fields are thriving, despite the vastly different economic climate we now live in, with its no-fun, belt-tightening effects on higher ed across the board.

Related Content:

Heat Mapping the Rise of Bruce Springsteen: How the Boss Went Viral in a Pre-Internet Era

Watch Documentaries on the Making of Pink Floyd’s Dark Side of the Moon and Wish You Were Here

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness