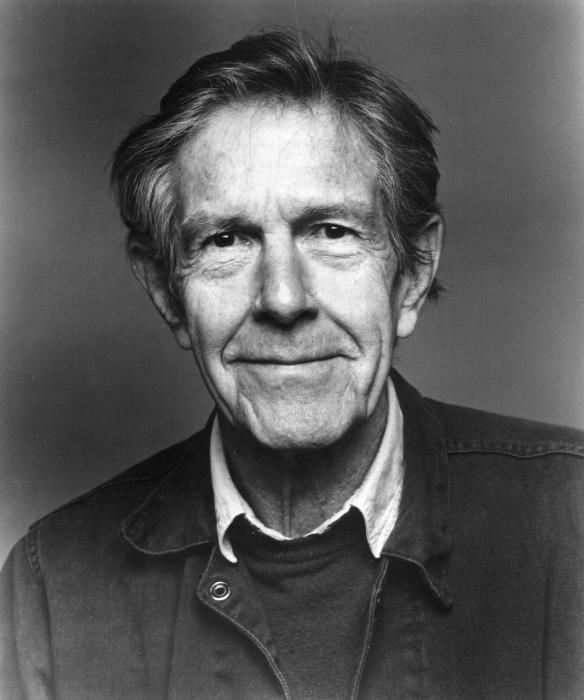

John Cage was born in 1915 and died in 1992. During that intervening time, he changed the face of avant-garde music and art.

An early disciple of Arnold Schoenberg, Cage made his biggest creative breakthrough by studying the I Ching, Zen Buddhism and the art of Marcel Duchamp. The composer decided to let elements of chance into his work. He started to write pieces for a “prepared piano” where things like thumbtacks, nails and forks were placed into the instrument’s strings to alter its sound in unexpected ways.

Cage’s most famous work, 4’33”, took conceptual music about as far as it could go. A musician walks out onto the stage, sits in front of a piano and does absolutely nothing for four minutes and thirty seconds. The sounds of the audience rustling, the traffic outside and any other ambient noise that might happen during that time period become a part of the piece. Watch a performance here.

The folks over at Ubu.com have placed online another one of Cage’s work, Diary: How To Improve The World (You Will Only Make Matters Worse) (1991). Clocking in at over 5 hours total, the piece is something of a Mount Everest of sound art.

Recorded in Switzerland a little over a year before his death, Diary features thoughts, observations and insights along with quotes from the likes of Buckminster Fuller, Henry David Thoreau and Mao Zedong. You can listen to Part 1 below, and click these links to listen to the remaining parts: Part 1, Part 2, Part 3, Part 4, Part 5, Part 6, Part 7, Part 8.

Cage’s diaries appeared previously in print as M: Writings, 1967–72. On the page, the text randomly changed both font and letter size. You can see what this looks like here. Cage and company reproduced this effect in the audio version by changing the position of the microphone and the recording volume. If you listen to Diary on headphones (which I recommend), you’ll hear Cage’s silken voice first behind your left ear, then in front of you and then, disconcertingly, inside your head.

Much of the time, Cage’s words will feel obscure and poetic. And then, as you’re lulled by the rhythm of his voice, he’ll hit you with something as profound as a Zen koan. (“The goal is not to have a goal.”) Just sit back and let the words flow over you.

Related Content:

Hear Joey Ramone Sing a Piece by John Cage Adapted from James Joyce’s Finnegans Wake

Watch a Surprisingly Moving Performance of John Cage’s 1948 “Suite for Toy Piano”

Woody Guthrie’s Fan Letter To John Cage and Alan Hovhaness (1947)

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.