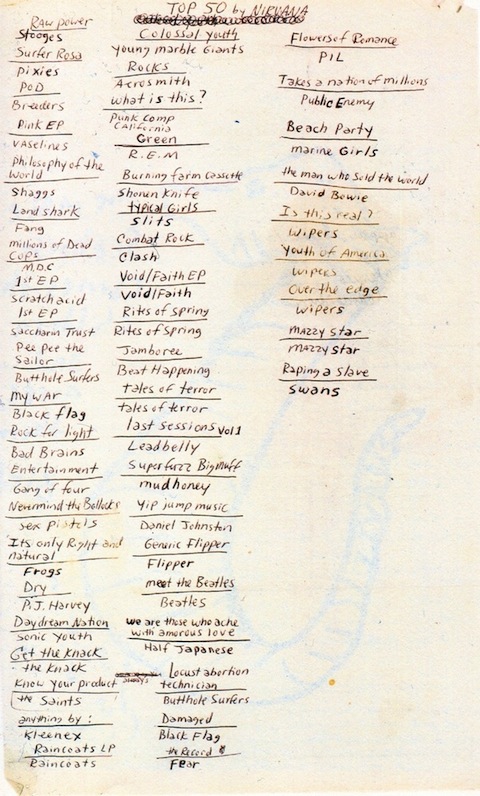

Circulating ‘round the internet recently is, wouldn’t you know it, yet another famous list of favorites. But it’s not a “listicle,” I’d say, one of those concocted clickbait hodgepodges that crop up in every corner with sometimes only the most tenuous, or lurid, of organizing principles. While we do have a tradition of showcasing lists here, they are generally on the order of those organically compiled by singular creative minds ranking and ordering their universes. I would say these things are true of Kurt Cobain’s list of albums above, which he titles “Top 50 by Nirvana” (see a full transcription at the bottom of the post, courtesy of Brooklyn Vegan). It not only presents a picture of the late Cobain and his bandmates’ musical heritage, it also offers us a genuine sampler of a generation’s protest music—plenty of classic angry ’80s hardcore punk and post-punk, lo-fi indie, a smattering of classic rock, some fringe outsiders like The Shaggs, and a rap album at #43, the fiercely political Public Enemy’s It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back, a record beloved of almost all children of the 80s.

Having had an almost identical musical education as Cobain, it seems from the list, I can’t say that I find any of the choices here particularly surprising. It almost looks to me like the ideal code for producing a 90s alternative star—just add talent, teen angst, and the look of a bedraggled homeless puppy. But a Flavorwire take on the list does call Public Enemy (see their “Fight the Power” video above) one of a handful of “fascinating surprises.” Other than this stylistic departure, many of the selections from the list are particularly significant as influences on Cobain’s songwriting, and some of the artists listed are those the band covered on occasion.

One of Cobain’s major influences can also be easily claimed by nearly every indie artist of the 90s: Austin, Texas’ Daniel Johnston, a savant songwriter who has weathered a lifelong struggle with bipolar disorder yet produced one of the most honest, touching, and funny bodies of work in the past few decades. Cobain namechecks Johnston’s 1983 Yip Jump Music, from which comes the song above, “Worried Shoes,” an almost perfect example of his poignant lyricism and deft handling of emotional disaffection. One can see the appeal of Johnston’s spare homemade folk-blues to a sensibility like Cobain’s: “I took my lucky break / And I broke it in two / Put on my worried shoes / My worried shoes.” Johnston’s reaction to the interest of artists like Nirvana, Mudhoney, Beck, the Butthole Surfers, and Wilco is typically understated. “Ah, it’s pretty cool,” he says, “The attention was nice, ya know. Sells a few records.”

Cobain’s debt to David Bowie is evident in his swiping of some of Bowie’s chord changes and melodic phrasing. A touchstone for the grunge star was “The Man Who Sold the World,” which of course the band covered (above, unplugged) and which many a naïve Nirvana fan assumes was a Cobain original. Cobain places the album, The Man Who Sold the World at #45. Bowie is quoted in rock bio Nirvana: The Chosen Rejects as saying he was “simply blown away” when he found out that Cobain liked his work. Bowie “always wanted to talk to him about his reasons for covering ‘The Man Who Sold the World’’ and said “it was a good straight forward rendition and sounded somehow very honest.” He also expressed surprise at being “part of America’s musical landscape.” However, when young fans would approach Bowie and compliment him on his cover of a “Nirvana song” after he played the tune, his reactions were less than polite. According to Nicholas Pegg, Bowie said, “kids that come up afterwards and say, ‘It’s cool you’re doing a Nirvana song.’ And I think, ‘Fuc& you, you little tosser!’”

No shortage of ’90s artists, like their ’60s folk-rock forebears, named Leadbelly as a primary influence. Cobain places the iconic bluesman’s Leadbelly’s Last Sessions Vol. 1 at number 33. Whether or not anyone can hear acoustic Delta blues in Nirvana, most people are familiar with their unplugged cover of the Leadbelly standard “In the Pines,” aka “Where Did You Sleep Last Night” (Cobain learned the song from Screaming Trees singer Mark Lanegan). Above is a rare, much darker, Nirvana cover of the song from a bootleg album of live recordings called Ultra Rare Trax, performed at Pachyderm Studios in Cannon Falls, MN in 1993. (We will never know, of course, what Leadbellly would have thought of Kurt Cobain, though your guesses are appreciated.)

If the Nirvana list did not include Black Flag, someone would have to add it. Cobain places the L.A. hardcore band’s My War at number 11 on the list (first place is reserved for Iggy and the Stooges Raw Power). Above, former Black Flag vocalist Henry Rollins explains in a 1992 segment of MTV’s late-night alternative video show 120 Minutes what he thought were the reasons for the band’s phenomenal success. “It doesn’t take an idiot to realize that the mass media continually underestimates the intelligence of their audience,” he says, “You know how dissatisfied you’ve been with a lot of mainstream rock and roll.” Rollins goes on: “When a band like Nirvana comes along who are kicking the real thing, you like it because it’s real.”

Not every one of the artists Cobain lists had such nice things to say about him in return, however. The Sex Pistols’ Never Mind the Bullocks gets slotted at #14 on the list. In his autobiography, former Pistols leader and infamous contrarian John Lydon apparently “reserved some venom for the likes of Nirvana,” writes reviewer Tim Kennedy, “comparing them to the clueless metal bands [the Sex Pistols] were up against in the seventies.” For all the millions of Nirvana fans during the band’s heyday, there was also a small contingent of kids who felt similarly, no matter how rarified or representative Cobain’s musical tastes. In some of those cases, no doubt, rival bands felt that way because, as Henry Rollins describes it, while they were still taking the bus, “the other guy is sneering at you from a block-long limo.”

Kurt Cobain’s Favorite Albums

1. Iggy and the Stooges, “Raw Power”

2. Pixies, “Surfer Rosa”

3. The Breeders, “Pod”

4. The Vaselines, “Pink EP”

5. The Shaggs, “Philosophy of the World”

6. Fang, “Landshark”

7. MDC, “Millions of Dead Cops”

8. Scratch Acid, “Scratch Acid EP”

9. Saccharine Trust, “Paganicons”

10. Butthole Surfers, “Pee Pee the Sailor” aka “Brown Reason to Live”

11. Black Flag, “My War”

12. Bad Brains, “Rock for Light”

13. Gang of Four, “Entertainment!”

14. Sex Pistols, “Never Mind the Bollocks”

15. The Frogs, “It’s Only Right and Natural”

16. PJ Harvey, “Dry”

17. Sonic Youth, “Daydream Nation”

18. The Knack, “Get the Knack”

19. The Saints, “Know Your Product”

20. anything by Kleenex

21. The Raincoats, “The Raincoats”

22. Young Marble Giants, “Colossal Youth”

23. Aerosmith, “Rocks”

24. Various Artists, “What Is It”

25. R.E.M., “Green”

26. Shonen Knife, “Burning Farm”

27. The Slits, “Typical Girls”

28. The Clash, “Combat Rock”

29. The Faith/Void, “Split EP”

30. Rites of Spring, “Rites of Spring”

31. Beat Happening, “Jamboree”

32. Tales of Terror, “Tales of Terror”

33. Leadbelly, “Leadbelly’s Last Sessions Vol. 1”

34. Mudhoney, “Superfuzz Bigmuff”

35. Daniel Johnston, “Yip/Jump Music”

36. Flipper, “Generic Flipper”

37. The Beatles, “Meet the Beatles”

38. Half Japanese, “We Are They Who Ache With Amorous Love”

39. Butthole Surfers, “Locust Abortion Technician”

40. Black Flag, “Damaged”

41. Fear, “The Record”

42. PiL, “Flowers of Romance”

43. Public Enemy, “It Takes a Nation of Millions to Hold Us Back”

44. Marine Girls, “Beach Party”

45. David Bowie, “The Man Who Sold the World”

46. Wipers, “Is This Real?”

47. Wipers, “Youth of America”

48. Wipers, “Over the Edge”

49. Mazzy Star, “She Hangs Brightly”

50. Swans, “Young God”

Related Content:

Animated Video: Kurt Cobain on Teenage Angst, Sexuality & Finding Salvation in Punk Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness