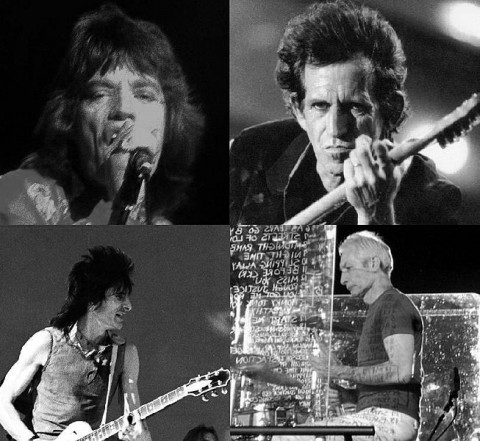

Image via Wikimedia Commons

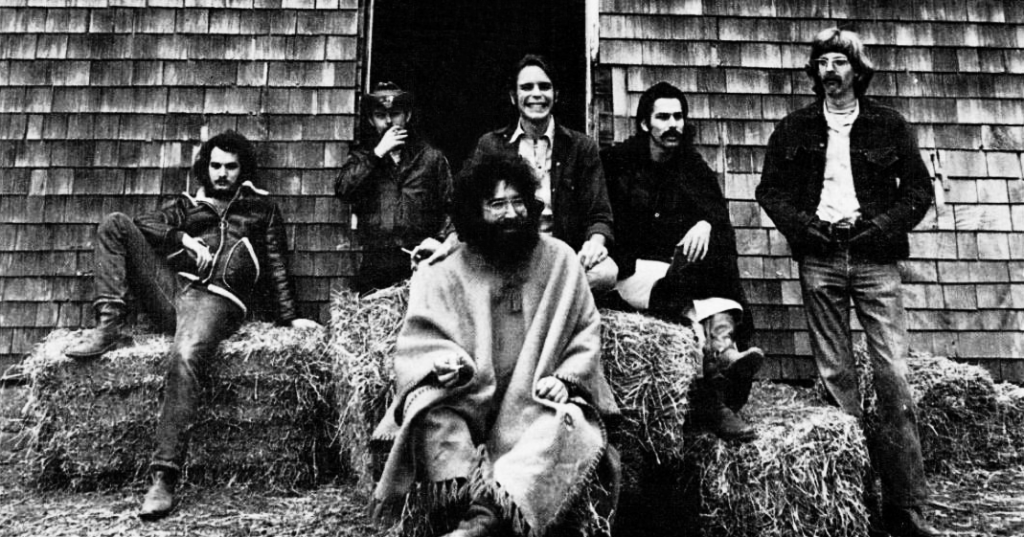

Even resolute non-Deadheads have been passing around “Deadhead,” Nick Paumgarten’s recent New Yorker piece on “the vast recorded legacy of the Grateful Dead.” Like much of the most interesting magazine journalism, the article digs deep into and provides a primer on a subculture that goes deep. Casual Dead listeners know there exists a large and dedicated body of fervently un-casual Dead listeners, the fans who may have followed the band around on its touring days but now collect every last one of its recorded performances, official, unofficial, or otherwise. “It was denser, feverish, otherworldly,” Paumgarten describes his first experience hearing a Dead bootleg. “If you took an interest, you’d copy a few tapes, listen to those over and over, until they began to make sense, and then copy some more. Before long, you might have a scattershot collection, with a couple of tapes from each year. It was all Grateful Dead, but because of the variability in sonic fidelity, and because the band had been at it for twenty years, there were many different flavors and moods. Even the compromised sound quality became a perverse part of the appeal. Each tape seemed to have its own particular note of decay, like the taste of the barnyard in a wine or a cheese.”

Do you aspire to join those Paumgarten calls “the tapeheads, the geeks, the throngs of workaday Phil Schaaps, who approach the band’s body of work with the intensity and the attention to detail that one might bring to birding, baseball, or the Talmud”? If so, the internet, and specifically the Internet Archive’s Grateful Dead collection, has cranked the barrier to entry way down. Its 11,215 free Grateful Dead recordings should keep you busy for some time. “You can browse the recordings by year, so if you click on, say, 1973 you will see links to two hundred and ninety-four recordings, beginning with four versions of a February 9th concert at Stanford and ending with several versions of December 19th in Tampa,” writes Paumgarten. “Most users merely stream the music; it’s a hundred cassette trays, in the Cloud.” If you need a break from these concerts, in all their variable-fidelity glory, listen to Paumgarten talk matters Dead with music critic Sasha Frere-Jones on the New Yorker Out Loud podcast (listen here). And if you find the Dead not quite to your taste — guitarist Jerry Garcia famously compared their dedicated niche audience to “people who like licorice” — why not move on to the Fugazi archive?

Related content:

Bob Dylan and The Grateful Dead Rehearse Together in Summer 1987. Listen to 74 Tracks.

NASA & Grateful Dead Drummer Mickey Hart Record Cosmic Sounds of the Universe on New Album

UC Santa Cruz Opens a Deadhead’s Delight: The Grateful Dead Archive is Now Online

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.