Having seen Radiohead a few times since their post-2000 Kid A transformation, I can tell you firsthand that while their last several records have trended toward bedroom rock, the live show is still a full-on experience. No twiddling behind laptops and drum machines. And if you haven’t had the pleasure of seeing them perform since their break with noisy alt-rock, now you can, thanks to the fans who produced the above film, shot at NYC’s Roseland Ballroom and the second of only three shows the band played in 2011 in support of The King of Limbs.

Edited together from the YouTube footage of ten different fans, the video is a remarkable example of crowdsourced dedication. Radiohead generously donated the audio straight from the soundboard, providing stellar sound, and the fan-editors obtained at least two camera angles for every song, giving this production the look of a professional concert film. It’s quite an achievement overall (and not the first time this has been done).

The producers of the film have made it available for free download (via torrent). You can find more information on the film at the project coordinator’s blogspot. The band and fan filmmakers ask that you consider donating any funds you might have used to purchase the film to organizations benefitting the Haiti Earthquake Fund, or to those helping Hurricane Sandy victims, such as Doctors without Borders or the Red Cross. The film is dedicated to Scott Johnson, the Radiohead drum technician who died in a stage collapse at an outdoor concert in Toronto last June.

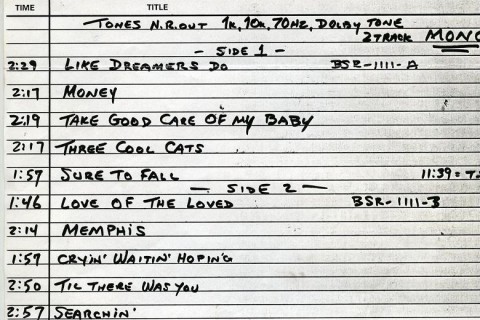

Finally, in the spirit of fan collaboration, YouTube user MountainMan1092 helpfully typed up and posted the tracklist below:

0:00:58 Bloom 0:07:23 Little By Little 0:12:07 Staircase 0:17:02 The National Anthem 0:22:03 Feral 0:26:20 Subterranean Homesick Alien 0:31:24 Like Spinning Plates 0:34:50 All I Need 0:39:06 True Love Waits/ Everything In Its Right Place 0:44:49 15 Step 0:49:04 Weird Fishes/ Arpeggi 0:55:08 Lotus Flower 1:00:55 Codex 1:06:43 The Daily Mail 1:10:33 Good Morning Mr. Magpie 1:16:22 Reckoner 1:24:00 Give Up The Ghost 1:29:19 Myxomatosis 01:33:24 Bodysnatchers 1:41:28 Supercollider 1:47:17 Nude

via Slate

Josh Jones is a doctoral candidate in English at Fordham University and a co-founder and former managing editor of Guernica / A Magazine of Arts and Politics.