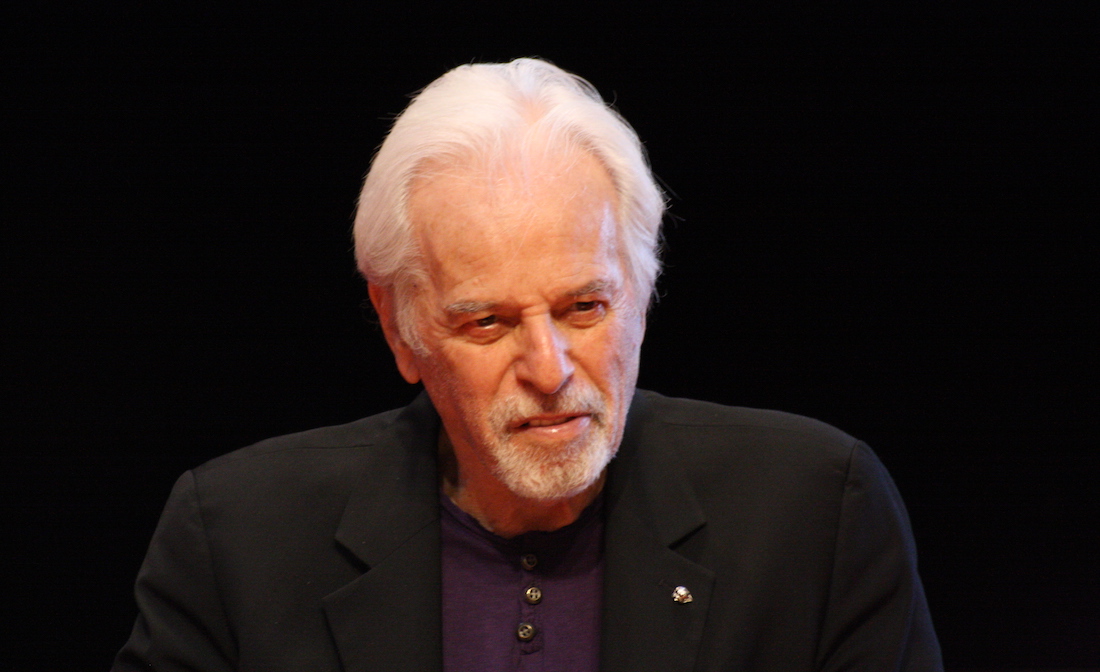

Creative Commons photo by Lionel Allorge

If you’re a fan of science fiction or the films of David Lynch, you’ve surely seen the 1984 film adaptation of Frank Herbert’s cult classic sci-fi novel, Dune (though Lynch himself may prefer that you didn’t). And indeed, it’s very likely that, by now, you’ve heard the incredible story of what Dune might have been, had it been directed ten years earlier by psychedelic Chilean filmmaker, writer, composer, and psychotherapist Alejandro Jodorowsky. Perhaps you even caught Jonathan Crow’s post on this site featuring Jodorowsky’s proposed storyboards—drawn by French artist Moebius—for what would most certainly would have been “a mind-bogglingly grand epic” of a movie. Alas, Jodorowsky’s Dune never came about, though it did later lead to the documentary Jodorowsky’s Dune, which Matt Zoller Seitz pronounced “a call to arms for dreamers everywhere.”

That description applies not only to the film about a film that could have been, but also to the entirety of Jodorowsky’s work, including his—thoroughly bizarre and captivating—early features, El Topo and The Holy Mountain, and the creation of a comic book universe like no other. Called “The Jodoverse,” the world of his comic books is, as writer Warren Ellis says, “astonishingly beautiful and totally mad”—again, a succinct description of Jodorowsky’s every artistic endeavor. Witness below, for example, the stunning trailer for his most recent feature film, 2014’s The Dance of Reality. You may find the visual excesses so overwhelming that you only half-hear the narration.

Listen (or read) carefully, however. Jodorowsky has as much to tell us with his cryptically poetic pronouncements as he does with his visionary imagery. Do you find his epigrams platitudinous, sententious, Pollyannaish, or naïve? Jodorowsky doesn’t mind. He calls, remember, to the dreamers, not the hard-bitten, cynical realists. And if you’re one of the dreamers who hears that call, you’ll find much to love in the list below of Jodorowsky’s 82 Commandments for living. But so too, I think, will the realists. These come from Jodorowsky’s memoir The Spiritual Journey of Alejandro Jodorowsky, and the list comes via Dangerous Minds, who adapted it from “the better part of three pages” of text.

As Jodorowsky frames these maxims in his book, they originated with influential Russian mystic George Gurdjieff, and were told to him by Gurdjieff’s daughter, Reyna d’Assia. Perhaps that’s so. But you’ll note, if you know Jodorowsky’s writing—or simply took a couple minutes time to watch the trailer above—that they sound enough like the author’s own words to have been brought forth from his personal storehouse of accumulated wisdom. In any case, Jodorowsky has always been quick to acknowledge his spiritual teachers, and whether these are his second-hand accounts of Gurdjieff or his own inventions has no bearing on the substance therein.

Often sounding very much like Biblical proverbs or Buddhist precepts, the commandments are intended, d’Assia says in Jodorowsky’s account, to help us “change [our] habits, conquer laziness, and become… morally sound human being[s].” As she remarks in the book, before she delivers the below in a lengthy monologue, “to be strong in the great things, we must also be strong in the small ones.” Therefore…

- Ground your attention on yourself. Be conscious at every moment of what you are thinking, sensing, feeling, desiring, and doing.

- Always finish what you have begun.

- Whatever you are doing, do it as well as possible.

- Do not become attached to anything that can destroy you in the course of time.

- Develop your generosity ‒ but secretly.

- Treat everyone as if he or she was a close relative.

- Organize what you have disorganized.

- Learn to receive and give thanks for every gift.

- Stop defining yourself.

- Do not lie or steal, for you lie to yourself and steal from yourself.

- Help your neighbor, but do not make him dependent.

- Do not encourage others to imitate you.

- Make work plans and accomplish them.

- Do not take up too much space.

- Make no useless movements or sounds.

- If you lack faith, pretend to have it.

- Do not allow yourself to be impressed by strong personalities.

- Do not regard anyone or anything as your possession.

- Share fairly.

- Do not seduce.

- Sleep and eat only as much as necessary.

- Do not speak of your personal problems.

- Do not express judgment or criticism when you are ignorant of most of the factors involved.

- Do not establish useless friendships.

- Do not follow fashions.

- Do not sell yourself.

- Respect contracts you have signed.

- Be on time.

- Never envy the luck or success of anyone.

- Say no more than necessary.

- Do not think of the profits your work will engender.

- Never threaten anyone.

- Keep your promises.

- In any discussion, put yourself in the other person’s place.

- Admit that someone else may be superior to you.

- Do not eliminate, but transmute.

- Conquer your fears, for each of them represents a camouflaged desire.

- Help others to help themselves.

- Conquer your aversions and come closer to those who inspire rejection in you.

- Do not react to what others say about you, whether praise or blame.

- Transform your pride into dignity.

- Transform your anger into creativity.

- Transform your greed into respect for beauty.

- Transform your envy into admiration for the values of the other.

- Transform your hate into charity.

- Neither praise nor insult yourself.

- Regard what does not belong to you as if it did belong to you.

- Do not complain.

- Develop your imagination.

- Never give orders to gain the satisfaction of being obeyed.

- Pay for services performed for you.

- Do not proselytize your work or ideas.

- Do not try to make others feel for you emotions such as pity, admiration, sympathy, or complicity.

- Do not try to distinguish yourself by your appearance.

- Never contradict; instead, be silent.

- Do not contract debts; acquire and pay immediately.

- If you offend someone, ask his or her pardon; if you have offended a person publicly, apologize publicly.

- When you realize you have said something that is mistaken, do not persist in error through pride; instead, immediately retract it.

- Never defend your old ideas simply because you are the one who expressed them.

- Do not keep useless objects.

- Do not adorn yourself with exotic ideas.

- Do not have your photograph taken with famous people.

- Justify yourself to no one, and keep your own counsel.

- Never define yourself by what you possess.

- Never speak of yourself without considering that you might change.

- Accept that nothing belongs to you.

- When someone asks your opinion about something or someone, speak only of his or her qualities.

- When you become ill, regard your illness as your teacher, not as something to be hated.

- Look directly, and do not hide yourself.

- Do not forget your dead, but accord them a limited place and do not allow them to invade your life.

- Wherever you live, always find a space that you devote to the sacred.

- When you perform a service, make your effort inconspicuous.

- If you decide to work to help others, do it with pleasure.

- If you are hesitating between doing and not doing, take the risk of doing.

- Do not try to be everything to your spouse; accept that there are things that you cannot give him or her but which others can.

- When someone is speaking to an interested audience, do not contradict that person and steal his or her audience.

- Live on money you have earned.

- Never brag about amorous adventures.

- Never glorify your weaknesses.

- Never visit someone only to pass the time.

- Obtain things in order to share them.

- If you are meditating and a devil appears, make the devil meditate too.

Related Content:

Moebius’ Storyboards & Concept Art for Jodorowsky’s Dune

Moebius Gives 18 Wisdom-Filled Tips to Aspiring Artists (1996)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness