Five years ago Polaroid announced that they would no longer make analog instamatic film. At that moment, if one listened carefully, one could almost hear some of the 20th century’s most famous artists wail in despair, even from the grave. Ansel Adams loved Polaroid and shot some of his famous Yosemite images in that format first.

But a technique with that kind of following doesn’t die off easily. Two ardent Polaroid fans—ardent enough to actually attend the closure of a Polaroid factory in the Netherlands—met and came up with a plan to save the factory and Polaroid instant film. They called their plan the Impossible Project. They leased one of the Dutch factory buildings and eventually fired up the machines again, turning out new instant film.

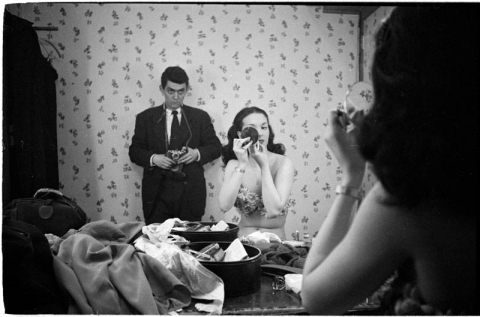

Lucky for us. Artists like David Hockney have long made beautiful use of Polaroid instant photos to construct cubist collages. One of the best at this is the Italian photographer Maurizio Galimberti who creates terrific celebrity portraits using a Polaroid.

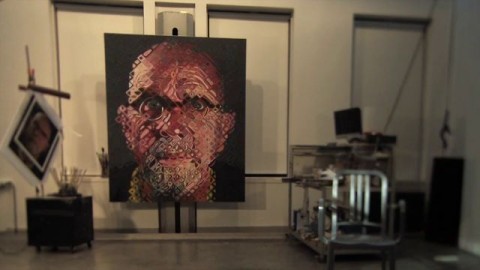

Galimberti considers himself a painter who uses a camera. Watching the video of his photo shoot with painter Chuck Close, it’s interesting to observe how similar Galimberti’s photo collage (above) is to Close’s own painted self-portraits.

Galimberti also has pretty good access to celebrities, having shot the portrait of Johnny Depp and this one of George Clooney at the 2003 Venice Film Festival.

Galimberti posts a number of more recent celebrity portraits on his website, where he also displays his abstract city photo collages.

Kate Rix writes about digital media and education. Visit her website: .