Stephen Hawking died last night at age of 76. I can think of no better, brief social media tribute than that from the @thetweetofgod: “It’s only been a few hours and Stephen Hawking already mathematically proved, to My face, that I don’t exist.” Hawking was an atheist, but he didn’t claim to have eliminated the idea with pure mathematics. But if he had, it would have been brilliantly elegant, even—as he used the phrase in his popular 1988 cosmology A Brief History of Time—to a theoretical “mind of God.”

Hawking himself used the word “elegant,” with modesty, to describe his discovery that “general relativity can be combined with quantum theory,” that is, “if one replaces ordinary time with so-called imaginary time.” In the bestselling A Brief History of Time, he described how one might possibly reconcile the two. His search for this “Grand Unified Theory of Everything,” writes his editor Peter Guzzardi, represented “the quest for the holy grail of science—one theory that could unite two separate fields that worked individually but wholly independently of each other.”

The physicist had to help Guzzardi translate rarified concepts into readable prose for bookbuyers at “drugstores, supermarkets, and airport shops.” But this is not to say A Brief History of Time is an easy read. (In the midst of that process, Hawking also had to learn how to translate his own thoughts again, as a tracheotomy ended his speech, and he transitioned to the computer devices we came to know as his only voice.) Most who read Hawking’s book, or just skimmed it, might remember it for its take on the big bang. It’s an aspect of his theory that piqued the usual creationist suspects, and thus generated innumerable headlines.

But it was the other term in Hawking’s subtitle, “from the Big Bang to Black Holes,” that really occupied the central place in his extensive body of less accessible scientific work. He wrote his thesis on the expanding universe, but gave his final lectures on black holes. The discoveries in Hawking’s cosmology came from his intensive focus on black holes, beginning in 1970 with his innovation of the second law of black hole dynamics and continuing through groundbreaking work in the mid-70s that his former dissertation advisor, eminent physicist Dennis Sciama, pronounced “a new revolution in our understanding.”

Hawking continued to revolutionize theoretical physics through the study of black holes into the last years of his life. In January 2016, he published a paper on arXiv.org called “Soft Hair on Black Holes,” proposing “a possible solution to his black hole information paradox,” as Fiona MacDonald writes at Science Alert. Hawking’s final contributions show that black holes have what he calls “soft hair” around them—or waves of zero-energy particles. Contrary to his previous conclusion that nothing can escape from a black hole, Hawking believed that this quantum “hair” could store information previously thought lost forever.

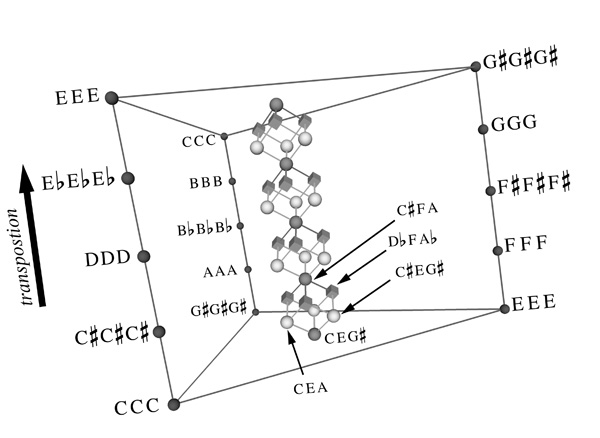

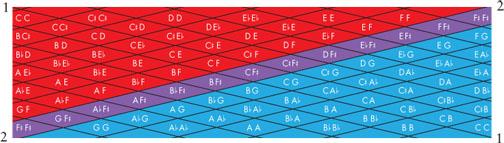

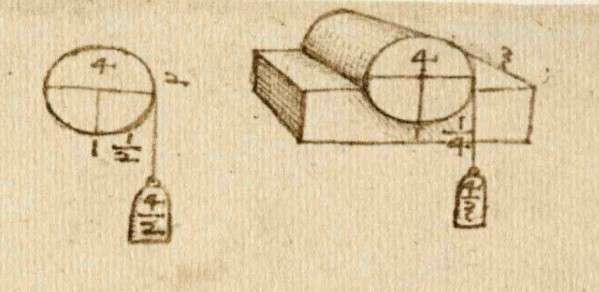

Hawking followed up these intriguing, but exceptionally dense, findings with a much more approachable text, his talks for the BBC’s Reith Lectures, which artist Andrew Park illustrated with the chalkboard drawings you see above. The first talk, “Do Black Holes Have No Hair?” walks us briskly through the formation of black holes and the big names in black hole science before moving on to the heavy quantum theory. The second talk continues to sketch its way through the theory, using striking metaphors and witticisms to get the point across.

Hawking’s explanations of phenomena are as profound, verging on mystical, as they are thorough. He doesn’t forget the human dimension or the emotional resonance of science, occasionally suggesting metaphysical—or meta-psychological—implications. Thanks in part to his work, we first thought of black holes as nihilistic voids from which nothing could escape. He left us, however with a radical new view, which he sums up cheerfully as “if you feel you are in a black hole, don’t give up, There’s a way out.” Or, even more Zen-like, as he proclaimed in a 2014 paper, “there are no black holes.”

Related Content:

Watch A Brief History of Time, Errol Morris’ Film About the Life & Work of Stephen Hawking

The Big Ideas of Stephen Hawking Explained with Simple Animation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness