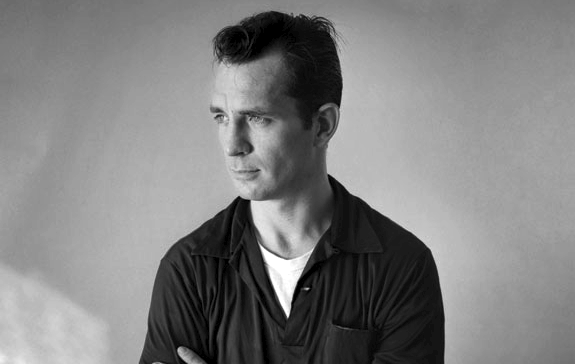

What makes Pablo Picasso such a representative 20th-century artist? Most of it has to do with his particular achievements, such as the visual ground he broke with his Cubist painting, sure, but some of it also has to do with the fact that his interests extended so far beyond painting. We think of creators who could create across various domains as “Renaissance men,” but conditions a few centuries on from the Renaissance enabled such artists to exert their will across an even wider range of forms. Picasso, for instance, worked in not just painting but sculpture, printmaking, ceramics, and letters.

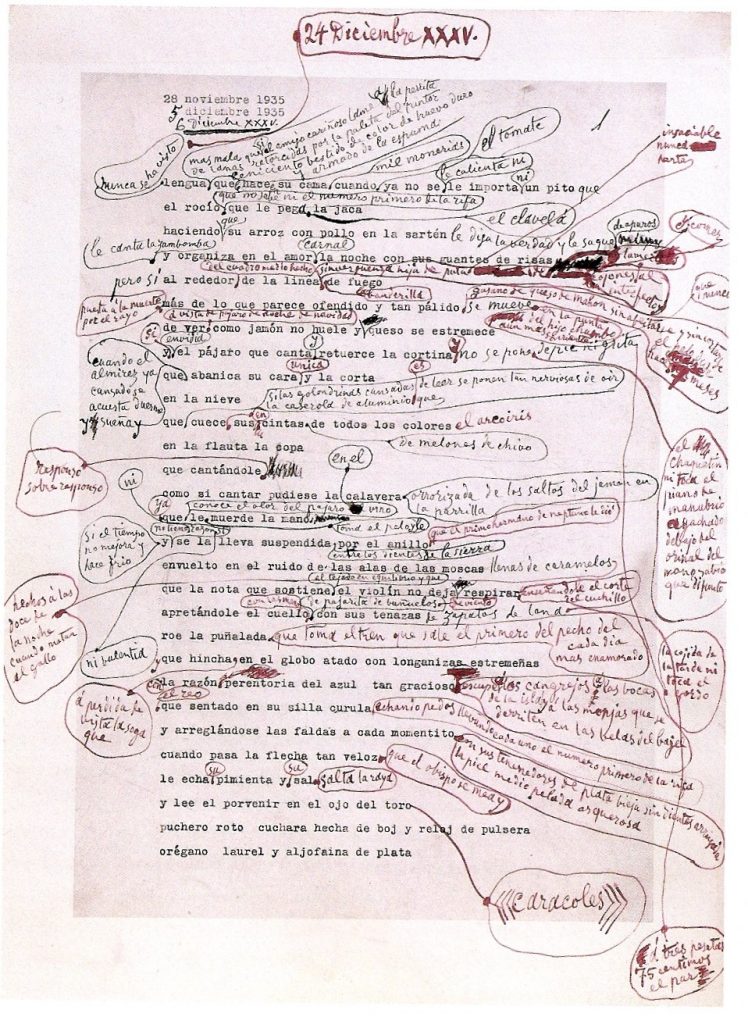

That last even includes poetry, to which Picasso announced his commitment in 1935, at the age of 53. At that point, writes Dangerous Minds’ Paul Gallagher, “he began writing poems almost every day until the summer of 1959,” beginning “by daubing colors for words in a notebook before moving on to using words to sketch images,” ultimately producing hundreds of poems composed primarily of “stream of consciousness, unpunctuated word association with startling juxtaposition of images and at times an obsession with sex, death and excrement.”

If this sounds like your cup of tea, you can find plenty of Picasso poetry over at Ubuweb, which offers A Picasso Sampler: Excerpts from the Burial of the Count of Orgaz & Other Poems free for the viewing. “Picasso, like any poet of consequence, is a man fully into his time and into the terrors that his time presents,” writes the collection’s editor Jerome Rothenberg. His words reflect “the state of things between the two world wars — the first one still fresh in mind and the rumblings of the second starting up,” a time and place “where poetry becomes — for him as for us — the only language that makes sense.”

Before diving into that collection, you can also get a sense of Picasso’s poetry by having a look at some of his shorter poems collected at the site of artist Jef Borgeau, such as “the artist & his model”:

turn your back

but stay in view at the same time

(now look away,

anything else confuses)stand still without saying a word

you can’t see but this is how

i separate day from nightand the starless sky

from the empty heart

“dogs”:

dogs eat at the night

buried in the yard

they chase the moon in a pack

the white of their teeth

compared to starsthe windows close against them

iron bars in transparencylife closes against them

the morning will crush them to dust

with only the wind left

to stir them up

And “the morning of the world”:

i have a face cut from ice

a heart pierced in a thousand places

so to remember

always the same voice

the same gestures

and my laughter

heavy

as a wall

between you and methe ones who are most alive

seem the most stillbehind the milky way

a shadow dancesour gaze climbs toward the stars

Related Content:

Pablo Picasso’s Two Favorite Recipes: Eel Stew & Omelette Tortilla Niçoise

The Postcards That Picasso Illustrated and Sent to Jean Cocteau, Apollinaire & Gertrude Stein

Colin Marshall writes on cities, language, Asia, and men’s style. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.