In English-speaking countries where Christmas is celebrated, A Christmas Carol, Charles Dickens’ secular Victorian tale of a Grinch restored to holiday cheer, usually plays some part.

How many children have been traumatized by Marley’s Ghost in the annual rebroadcast of the half hour, 1971 animated version, featuring the voices of Alistair Sim and Michael Redgrave as Scrooge and Bob Cratchit?

Personally, I lived in mortal fear of the cowled Ghost of Christmas Yet to Come from Scrooge, a movie musical version starring Albert Finney.

Adaptations have been built around everyone from the Muppets to Bill Murray.

And in some lucky families, an older relative with a flair for the theatrical reads the story aloud, preferably on the actual day.

It’s a tradition that Charles Dickens himself observed. It must’ve been a very picturesque scene, with his wife and all ten of their children gathered around. (Presumably his mistress was not included in the festivities).

Eventually, the torch was passed to the next generation, who mimicked and preserved the cadences favored by the master.

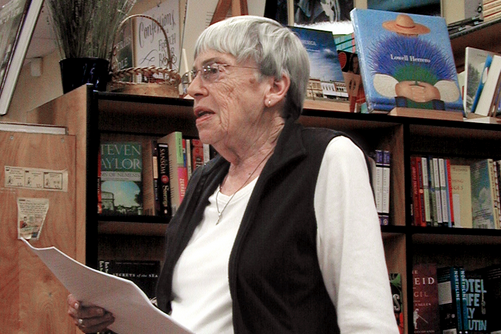

Dickens great-granddaughter, novelist Monica Dickens, who narrated a condensed version of the classic tale in 1984, above, was schooled in the family interpretation by her grandfather, Henry Fielding Dickens, who said of his famous father:

I remember him as being at his best either at Christmas time or at other times when Gad’s Hill was full of guests, for he loved social intercourse and was a perfect host. At such times he rose to the very height of the occasion, and it is quite impossible to express in words his geniality and brilliancy amid a brilliant circle.

Before the reading, Ms. Dickens shares some charming anecdotes about the original publication, but those with limited time and/or a Scrooge-like aversion to jolly intros can skip ahead to 7:59, when Big Ben chimes to signal the start of the story proper.

Her reading originally aired on Cape Cod’s radio station, 99.9 the Q. The reading will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

Related Content:

Charles Dickens’ Hand-Edited Copy of His Classic Holiday Tale, A Christmas Carol

A Christmas Carol, A Vintage Radio Broadcast by Orson Welles and Lionel Barrymore (1939)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday