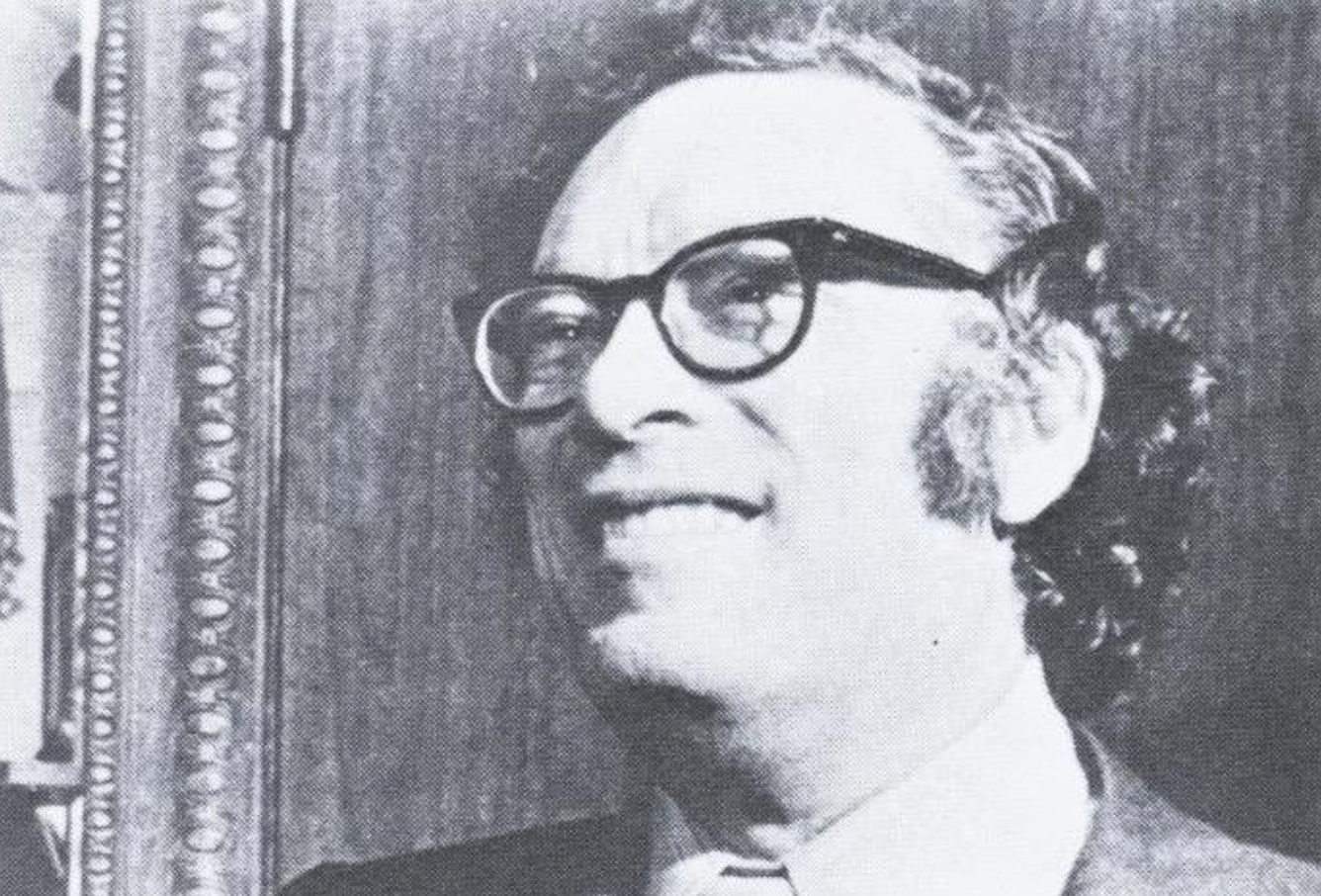

Rochester Institute of Technology, via Wikimedia Commons

Isaac Asimov’s hugely influential science fiction classic The Foundation Trilogy will soon, it seems, become an HBO series, reaching the same audiences who were won over by the Game of Thrones adaptations. We can expect favorite character arcs to emerge, perhaps distorting the original narrative; we can expect plenty of internet memes and new ripples of influence through successive generations. In fact, if the series becomes a reality, and catches on the way most HBO shows do—either with a mass audience or a later devoted cult following—I think we can expect much renewed interest in the field of “psychohistory,” the futuristic science practiced by the novels’ hero Hari Seldon.

?si=Xfh61enLrJbhctd_

This is no small thing. Foundation has inspired a great many science fiction writers, from Douglas Adams to George Lucas. But it has also guided the careers of people whose work has more immediate real-world consequences, like economist Paul Krugman and fervent advocate of positive psychology Martin Seligman. “The trilogy really is a unique masterpiece,” writes Krugman,” there has never been anything quite like it.” The fictional science of psychohistory inspired the experimental predictive techniques Seligman developed and described in his book Learned Optimism:

In his impossible-to-put-down Foundation Trilogy—I read it in one thirty-hour burst of adolescent excitement—Asimov invents a great hero for pimply, intellectual kids…. “Wow!” thought this impressionable adolescent…. That “Wow!” has stayed with me all my life.

If you’re thinking that the epic scale of Asimov’s sprawling trilogy—one he explicitly modeled after Edward Gibbon’s multi-volume History of the Decline and Fall of the Roman Empire—will prove impossible to realize on the screen, you may be right. On the other hand, Asimov’s prose has lent itself particularly well to an older dramatic medium: the radio play. As we noted in an earlier post on a popular 1973 BBC adaptation of the trilogy, Ender’s Game author Orson Scott Card once described the books as “all talk, no action.” This may sound like a disparagement, except, Card went on to say, “Asimov’s talk is action.”

Today, we bring you several different radio adaptations of Asimov’s fiction, and you can hear the many ways his fascinating concepts, translated into equally fascinating, and yes, talky, fiction, have inspired writers, scientists, filmmakers, and “pimply, intellectual kids” alike for decades. At the top of the post, hear the entire, eight-hour BBC adaptation of Foundation from start to finish. You can also stream and download individual episodes on Spotify and at Youtube and the Internet Archive. Below it, we have classic sci-fi radio drama series Dimension X’s dramatizations of “Pebble in the Sky” and “Nightfall,” both from 1951.

Also hear two Asimov’s stories “The ‘C’ Chute” and “Hostess”—both produced by Dimension X successor X Minus One. These series, wrote Colin Marshall in a previous post, “showcase American culture at its mid-20th-century finest: forward-looking, temperamentally bold, technologically adept, and saturated with earnestness but for the occasional surprisingly knowing irony or bleak edge of darkness.”

Not to be outdone by these two programs, Mutual Broadcasting System created Exploring Tomorrow, a “science fiction show of science-fictioneers, by science-fictioneers and for science-fictioneers” that ran briefly from 1957 to 1958. Below, they adapt Asimov’s story “The Liar.”

These old-time radio dramas will certainly appeal to the nostalgia of people who were alive to hear them when they first aired. But while their production values will never come close to matching those of HBO, they offer something for younger listeners as well—an opportunity to get lost in Asimov’s complex ideas, and to engage the imagination in ways television doesn’t allow. Whether or not Foundation ever successfully makes it to the small screen, I would love to see Asimov’s fiction—in print, on the radio, on screen, or on the internet—continue to inspire new scientific and social visionaries for generations to come.

Related Content:

Isaac Asimov’s Favorite Story “The Last Question” Read by Isaac Asimov— and by Leonard Nimoy

Isaac Asimov’s Foundation Trilogy: Hear the 1973 Radio Dramatization

X Minus One: More Classic 1950s Sci-Fi Radio from Asimov, Heinlein, Bradbury & Dick

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness