Photo by Sebastiaan term Burg via Wikimedia Commons

At the lower range of hearing, it’s said humans can hear sound down to about 20 Hz, beneath which we encounter a murky sonic realm called “infrasound,” the world of elephant and mole hearing. But while we may not hear those lowest frequencies, we feel them in our bodies, as we do many sounds in the lower frequency ranges—those that tend to disappear when pumped through tinny earbuds or shopping mall speakers. Since bass sounds don’t reach our ears with the same excited energy as the high frequency sounds of, say, trumpets or wailing guitars, we’ve tended to dismiss the instruments—and players—who hold down the low end (know any famous tuba players?).

In most popular music, bass players don’t get nearly enough credit—even when the bass provides a song’s essential hook. As Led Zeppelin’s John Paul Jones joked at his Rock and Roll Hall of Fame induction ceremony in 1995, “thank you to my friends for remembering my phone number.” And yet, writes Tom Barnes at Mic, “there’s scientific proof that bassists are actually one of the most vital members of any band…. It’s time we started treating bassists with the respect they deserve.” Research into the critical importance of low frequency sound explains why bass instruments mostly play rhythm parts and leave the fancy melodic noodling to instruments in the upper range. The phenomenon is not specific to rock, funk, jazz, dance, or hip hop. “Music in diverse cultures is composed this way,” says psychologist Laurel Trainor, director of the McMaster University Institute for Music and the Mind, “from classical East Indian music to Gamelan music of Java and Bali, suggesting an innate origin.”

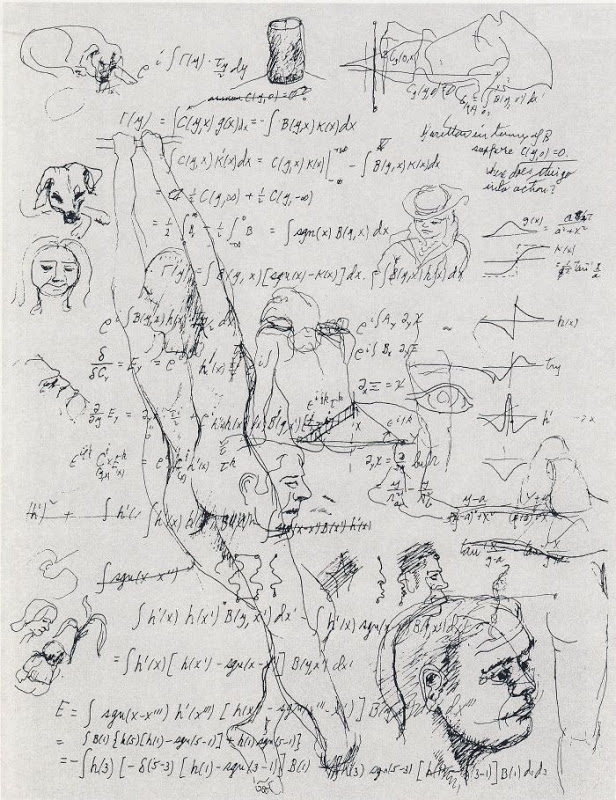

Trainor and her colleagues have recently published a study in the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences suggesting that perceptions of time are much more acute at lower registers, while our ability to distinguish changes in pitch gets much better in the upper ranges, which is why, writes Nature, “saxophonists and lead guitarists often have solos at a squealing register,” and why bassists tend to play fewer notes. (These findings seem consistent with the physics of sound waves.) To reach their conclusions, Trainer and her team “played people high and low pitched notes at the same time.” Participants were hooked up to an electroencephalogram that measured brain activity in response to the sounds. The psychologists “found that the brain was better at detecting when the lower tone occurred 50 MS too soon compared to when the higher tone occurred 50 MS too soon.”

The study’s title perfectly summarizes the team’s findings: “Superior time perception for lower musical pitch explains why bass-ranged instruments lay down musical rhythms.” In other words, “there is a psychological basis,” says Trainor, “for why we create music the way we do. Virtually all people will respond more to the beat when it is carried by lower-pitched instruments.” University of Vienna cognitive scientist Tecumseh Fitch has pronounced Trainor and her co-authors’ study a “plausible hypothesis for why bass parts play such a crucial role in rhythm perception.” He also adds, writes Nature:

For louder, deeper bass notes than those used in these tests, people might also feel the resonance in their bodies, not just hear it in their ears, helping us to keep rhythm. For example, when deaf people dance they might turn up the bass and play it very loud, he says, so that “they can literally ‘feel the beat’ via torso-based resonance.”

Painfully awkward revelers at weddings, on cruise ships, at high school reunions—they just can’t help it. Maybe even this dancing owl can’t help it. Some of us keep time better than others, but most of us feel and respond physically to low-frequency rhythms.

Bass instruments don’t only keep time; they also play a key role in a song’s harmonic and melodic structure. In 1880, an academic music textbook informed its readers that “the bass part… is, in fact, the foundation upon which the melody rests and without which there could be no melody.” As true as this was at the time—-when acoustic precursors to electric bass, synthesizers, and sub-bass amplification provided the low end—it’s just as true now. And bass parts often define the root note of a chord, regardless of what other instruments are doing. As a bass player, notes Sting, “you control the harmony,” as well as anchoring the melody. It seems the importance of rhythm players, though overlooked in much popular appreciation of music, cannot be overstated.

Related Content:

Hear Isolated Tracks From Five Great Rock Bassists: McCartney, Sting, Deacon, Jones & Lee

The Story of the Bass: New Video Gives Us 500 Years of Music History in 8 Minutes

7 Female Bass Players Who Helped Shape Modern Music: Kim Gordon, Tina Weymouth, Kim Deal & More

The Neuroscience of Drumming: Researchers Discover the Secrets of Drumming & The Human Brain

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness