“Everyone helplessly watching something beautiful burn is 2019 in a nutshell,” wrote TV critic Ryan McGee on Twitter the day a significant portion of Notre Dame burned to the ground. He might have included 2018 in his metaphor, when Brazil’s National Museum was totally destroyed by fire. Before the Parisian monument caught flame, people watched helplessly as historic black churches burned in the U.S., and while the museum and cathedral fire were not the direct result of evil intent, in all of these events we witnessed the loss of sanctuaries, a word with both a religious meaning and a secular one, as columnist Jarvis DeBerry points out.

Sanctuaries are places where people, priceless artifacts, and knowledge should be “safe and protected,” supposedly institutional bulwarks against disorder and violence. They are both havens and potent symbols—and they are also physical spaces that can be rebuilt, if not replaced.

And 21st-century technology has made their rebuilding a far more collaborative and more precise affair. The reconstruction of churches in Louisiana can be funded through social media. The contents of the National Museum of Brazil can be recollected, virtually at least, through crowdsourcing and digital archives.

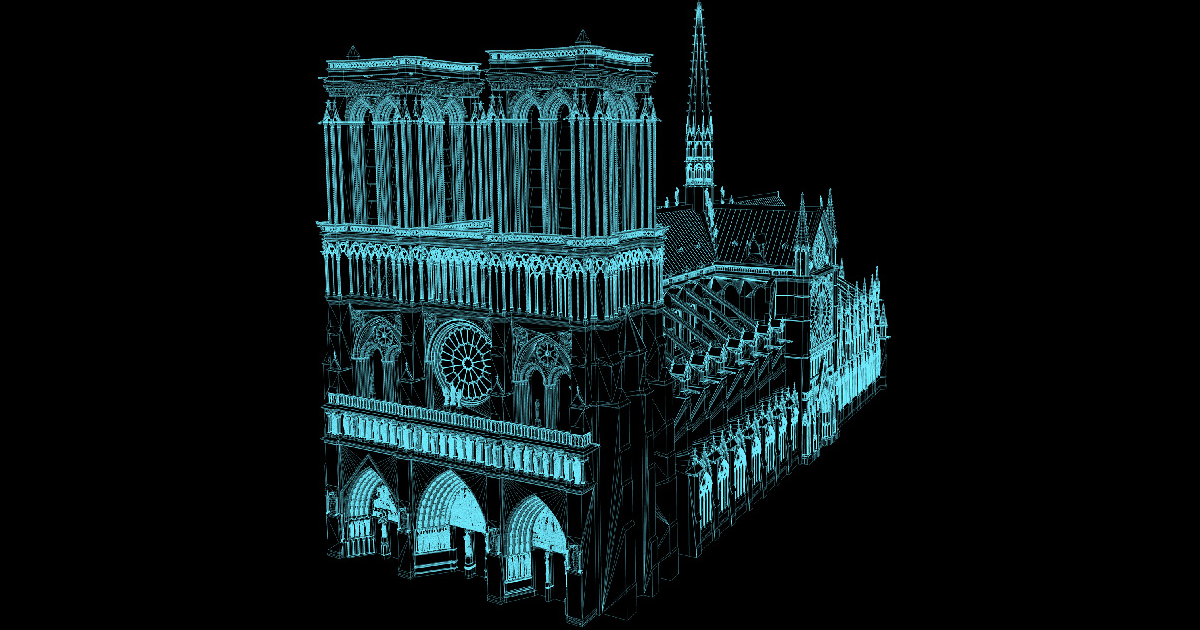

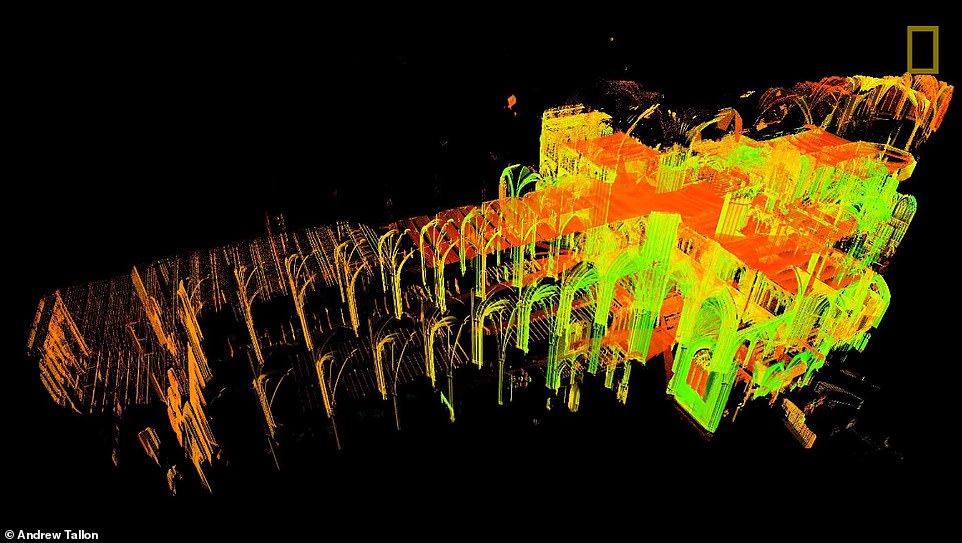

And the ravaged wood frame, roof, and spire of Notre Dame can be rebuilt, though never replaced, not only with millions in funding from Apple and fashion’s biggest houses, but with an exact 3D digital scan of the cathedral made in 2015 by Vassar art historian Andrew Tallon, who passed away last year from brain cancer. In the video at the top, see Tallon, then a professor at Vassar, describe his process, one driven by a lifelong passion for Gothic architecture, and especially for Notre Dame. A “former composer, would-be monk, and self-described gearhead,” wrote National Geographic in a 2015 profile of his work, Tallon brought a unique sensibility to the project.

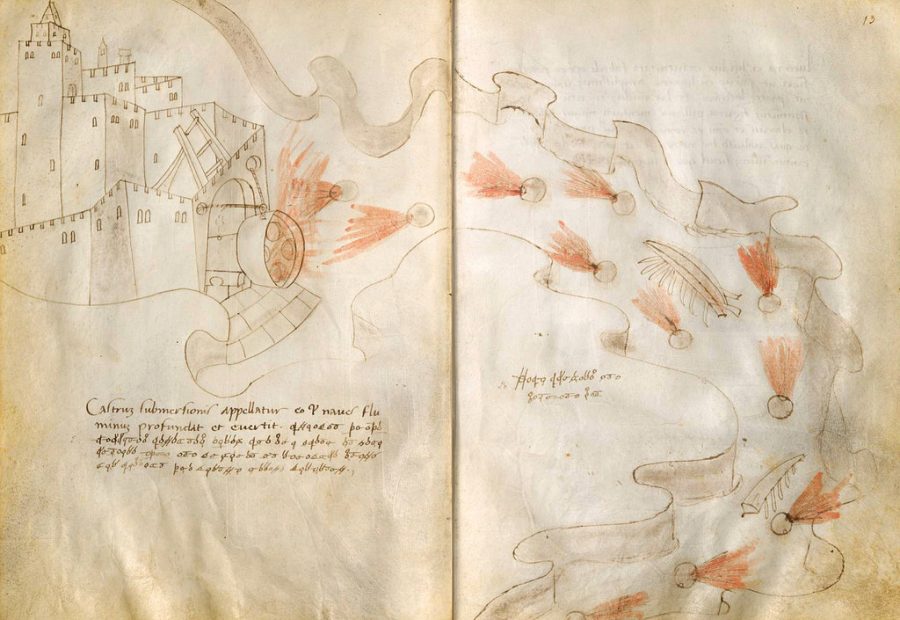

His fascination with the spaces of Gothic cathedrals began with an investigation into their acoustic properties. He developed the idea of using laser scanners to create a digital replica of Notre Dame after studying at Columbia under art historian Stephen Murray, who tried and failed in 2001 to make a laser scan of a cathedral north of Paris. Fourteen years later, the technology finally caught up with the idea, which Tallon also improved on by attempting to reconstruct not only the structure, but also the methods the builders used to build it yet did not record in writing.

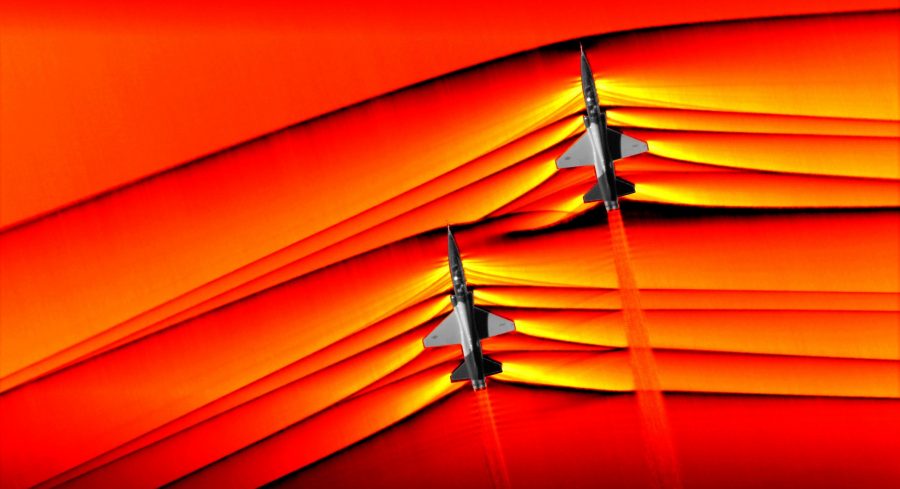

By examining how the cathedral moved when its foundations shifted or how it heated up or cooled down, Tallon could reveal “its original design and the choices that the master builder had to make when construction didn’t go as planned.” He took scans from “more than 50 locations around the cathedral—collecting more than one billion points of data.” All of the scans were knit together “to make them manageable and beautiful.” They are accurate to the millimeter, and as Wired reports, “architects now hope that Tallon’s scans may provide a map for keeping on track whatever rebuilding will have to take place.”

To learn even more about Tallon’s meticulous process than he reveals in the National Geographic video at the top, read his paper “Divining Proportions in the Information Age” in the open access journal Architectural Histories. We may not typically think of the digital world as much of a sanctuary, and maybe for good reason, but Tallon’s masterwork poignantly shows the importance of using its tools to record, document, and, if necessary, reconstruct the real-life spaces that meet our definitions of the term.

via the MIT Technology Review

Related Content:

Notre Dame Captured in an Early Photograph, 1838

A Virtual Time-Lapse Recreation of the Building of Notre Dame (1160)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness