When I was a little boy, I thought the greatest thing in the world would be to be able to make records. — Fred Rogers

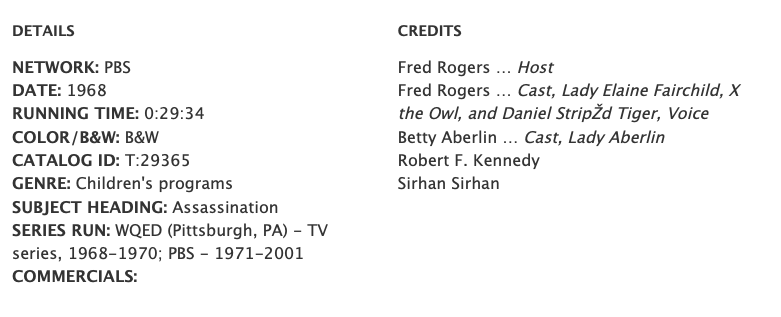

By 1972, when the above episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood aired, host Fred Rogers had already cut four records, including the hit-filled A Place of Our Own.

But a childlike curiosity compelled him to explore on camera how a virgin disc could become that most wondrous thing—a record.

So he borrowed a “special machine”—a Rek-O-Kut M12S overhead with an Audax mono head, for those keeping score at home—so he could show his friends, on camera, “how one makes records.”

This technology was already in decline, ousted by the vastly more portable home cassette recorder, but the record cutter held far more visual interest, yielding hair-like remnants that also became objects of fascination to Mister Rogers.

What we wouldn’t give to stumble across one of those machines and a stash of blank discs in a thrift store…

Wait, scratch that, imagine running across the actual platter Rogers cut that day!

Though we’d be remiss if we failed to mention that a member of The Secret Society of Lathe Trolls, a forum devoted to “record-cutting deviants, renegades, professionals & experimenters,” claims to have had an aunt who worked on the show, and according to her, the “reproduction” was faked in post.

(“It sounded like they recorded the repro on like an old Stenorette rim drive reel to reel or something and then piped that back in,” another commenter promptly responds.)

The Trolls’ episode discussion offers a lot of vintage audio nerd nitty gritty, as well as an interesting history of the one-off self-recoded disc craze.

The mid-century general public could go to a coin-operated portable sound booth to record a track or two. Spoken word messages were popular, though singers and bands also took the opportunity to lay down some grooves.

Radio stations and recording studios also kept machines similar to the one Rogers is seen using. Sun Records’ secretary, Marion Keisker, operated the cutting lathe the day an unknown named Elvis Presley showed up to cut a lacquered disc for a fee of $3.25.

The rest is history.

More recently, The Shins, The Kills, and Seasick Steve, below, recorded live direct-to-acetate records on a modified 1953 Scully Lathe at Nashville’s Third Man Records.

(Legend has it that James Brown’s “It’s A Man’s World” was cut on that same lathe… Cut a hit of your own during a tour of Third Man’s direct-to-acetate recording facilities.)

via @wfmu

Related Content:

How Old School Records Were Made, From Start to Finish: A 1937 Video Featuring Duke Ellington

Watch a Needle Ride Through LP Record Grooves Under an Electron Microscope

How Vinyl Records Are Made: A Primer from 1956

An Interactive Map of Every Record Shop in the World

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine, current issue the just-released #60. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.