Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus and share intelligent media with your friends! They’ll thank you for it.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus and share intelligent media with your friends! They’ll thank you for it.

I haven’t frequented Starbucks for a long time, but when I did, I could never get into their lingo. Do you want a “grande,” the “barista” asked? No, just give me a medium, ok? And if I ever tired of the irritating lingo battles, I headed to an indie cafe where simple language made sense.

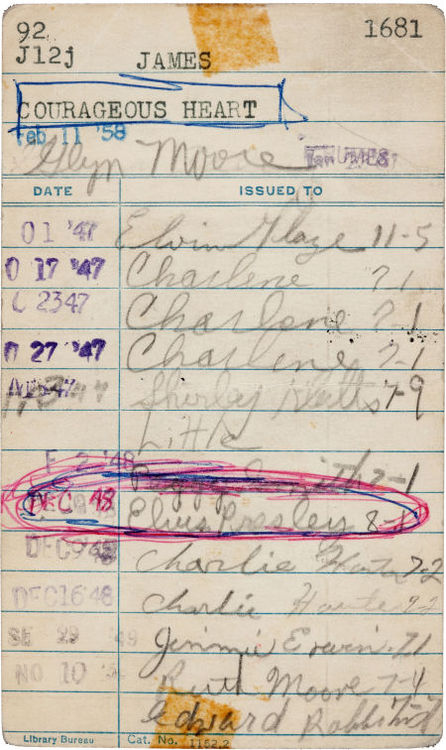

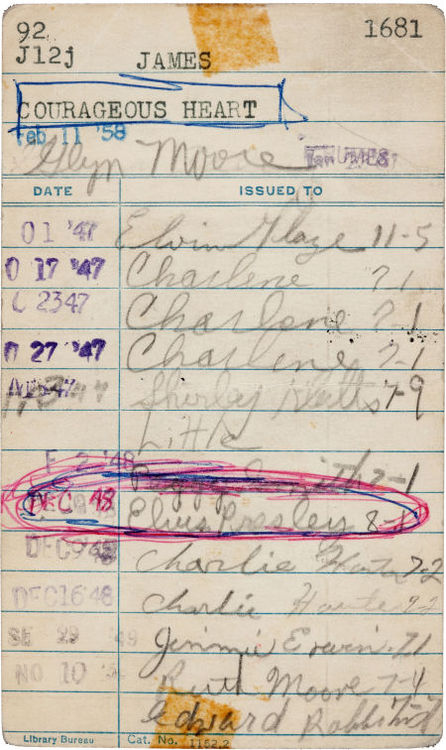

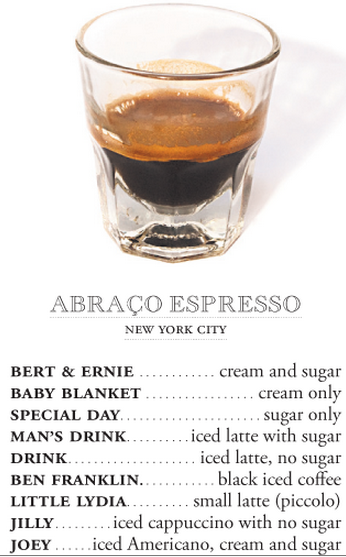

Nowadays, you apparently can’t bank on the indies for an escape. This weekend, The New York Times has a huge spread revealing the private vocabularies of America’s indie coffee bars, the places where you can now order “Cappuccigos,” “Jillys,” “Kanskis,” and a “Frankencaf,” along with some “Bert & Ernie,” apparently the new way of saying cream and sugar. If you care to speak Java Jive, you’ll want to spend time with this spread. It’s almost something we could add to our list of Free Foreign Language Lessons.

And now for some more coffee randomness:

Everything You Wanted to Know About Coffee in Three Minutes

“The Vertue of the COFFEE Drink”: London’s First Cafe Creates Ad for Coffee in the 1650s

The Physics of Coffee Rings Finally Explained

Jim Henson’s Violent Wilkins Coffee Commercials (1957–1961)

Vi Hart, the Khan Academy’s resident “Recreational Mathemusician” turns the space-time continuum into something that can be played forwards, backwards, upside down, in a circle, and on a Möbius strip.

How you ask?

Music. You know, that stuff that Shakespeare rhapsodized as the food of love?

The fast-talking Hart has way too much to prove in her less than eight minute video to waste time waxing poetic. To her, even the most elusive concepts are explainable, representable. She does manage to create some unintentionally lovely little melodies on a music box that reads holes punched through the notations on a tape printed with a musical stave.

It took several viewings for me to wrap my mind around what exactly was being demonstrated, but I think I’m beginning to grope my way toward whatever dimension she’s currently inhabiting. See if you can follow along and then weigh in as to what you think the mathematically-inclined Bach might be doing in his grave as Hart blithely feeds one of his compositions through her music box, upside down, and backwards.

Related Content:

How a Bach Canon Works. Brilliant.

85,000 Classical Music Scores (and Free MP3s) on the Web

A Big Bach Download – All Bach Organ Works for Free

Ayun Halliday took piano lessons for years. All that remains are the opening bars to Hello Dolly. Follow her @AyunHalliday

Living room, 2001:

In 1967, executives at CBS television made a bold move and changed the network’s long-running documentary series, The 20th Century, from a program looking back at the past to one looking ahead to the future. The 21st Century, as it was renamed, was hosted by Walter Cronkite and ran for three seasons. In one of the early episodes, “At Home, 2001,” which aired on March 12, 1967, Cronkite cites a government report predicting that by the year 2000, technology will have lowered the average American work week to 30 hours, with a one-month vacation. What will people do with all that free time? In the scene above, Cronkite makes a fairly accurate prediction of today’s state-of-the-art home entertainment systems. Although the knobs and dials look a bit archaic, the basic principle is there. But whatever happened to that 30-hour work week?

Home office, 2001:

“Now this is where a man might spend most of his time in the 21st century,” says Cronkite as he walks into the home office of the future, above. “This equipment will allow him to carry on normal business activities without ever going to an office away from home.”

In envisioning the office of the future as a masculine domain, Cronkite makes the same mistake as Stanley Kubrick and Arthur C. Clarke of imagining technological change without social change. (Remember the moon shuttle stewardess in 2001: A Space Odyssey?) But he otherwise offers a fairly prescient vision of some of the home computing, Internet and telecommunications advances that have indeed come to pass.

Kitchen, 2001:

Cronkite’s powers of prediction fail him when he reaches the Rube Goldbergian “kitchen of 2001,” which mistakes gratuitous automation for convenience. As one YouTube commentator said of the clip above, the only thing that resembles the kitchen of today is the microwave oven–and microwaves already existed in 1967.

But “At Home, 2001,” is much more thought-provoking than a few “gee whiz” predictions about the gadgets of the future. Cronkite interviews the architect Philip Johnson and other leading designers of his day for a deeper discussion about the tension that exists between our deep-seated, basically agrarian expectations for a home and the realities of urban congestion and suburban sprawl. You can watch the complete 25-minute program at A/V Geeks. And to read more about it, see Matt Novak’s piece at PaleoFuture. “Can we find a compromise between our increasingly urban way of living and the pride and privacy of the individual home?” asks Cronkite at the end of the program. “It will take decisions that go beyond technology, decisions about the quality of the life we want to lead, to answer the question ‘How will we live in the 21st century?’ ”

via Kottke

Related Content:

Arthur C. Clarke Predicts the Future in 1964 … And Kind of Nails It

The Internet Imagined in 1969

Marshall McLuhan: The World is a Global Village

1930s Fashion Designers Imagine How People Would Dress in the Year 2000

The White Stripes’ song “Little Room” is all about re-connecting with the space of creativity within you—the “little room” where emotions become ideas—when you’re feeling overwhelmed (by success? Or maybe just kids, bills and the IRS). Their garage-rock ditty is a nice marriage of form and content, the lyrical simplicity enacts the mental paring down Jack White recommends. No telling how often White goes to his “little room,” but he’s such a wellspring of songwriting ideas, solo and in a constellation of side projects, that I’d guess it’s pretty often. As a songwriter myself, I have found White’s advice utterly unimpeachable (which must be why I dutifully ignore it so often).

But the little room isn’t just a comforting place in the head, like Happy Gilmore’s happy place. It’s also a physical space—differently arranged for artists of different media. For the singer/songwriter, it’s generally a familiar, secluded place where you can put all of your focus on a guitar, a notepad, and a recording device (the simpler the better). That’s the space conjured up by The Acoustic Guitar Project, “created to help musicians reconnect to the original moment that inspired them to be singer-songwriters.” Conceived in April, 2012, the project’s stated mission is threefold:

If these goals sound a little too vague and pollyannaish to communicate much, listen to the wonderful simplicity of The Acoustic Guitar Project’s premise: 1) the project selects a musician, and provides him or her with an acoustic guitar and a handheld recorder. 2) the musician must produce an original song within one week, using only the equipment provided. 3) the musician, once finished, chooses the next musician for the project, and, I suppose, “pays it forward.”

It’s a really neat idea, and you can see the results on the site, which features over forty singer/songwriters so far who have been passed the guitar. Each musician has their own page with a profile, photo, and the audio and lyrics of their song. The first three stages of the project took place in New York City, Helsinki, Finland, and Bogota, Columbia, respectively, and the fourth stage moves to Port-au-Prince, Haiti. Joel Waldman of Bogota is one of these brave troubadours. You can see him perform his song, “Como Una Llama” (Like a Flame) live above. (See Joel’s page for the lyrics to his song, in both Spanish and English.) In the video below, Joel very thoughtfully discusses the feeling of writing a song—a process, he says, of combining information and inspiration.

Related Content:

James Taylor Gives Free Acoustic Guitar Lessons Online

The Best Music to Write By: Give Us Your Recommendations

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness

“Film found me,” says Spike Lee in the clip above from mediabistro’s “My First Big Break” series. We may now know him as one of his generation’s most outspoken, conviction-driven American filmmakers, but he says he only got into the game because he couldn’t land a job. Entering the long, hot, unemployed summer of 1977, the young Lee spied a Super‑8 movie camera in a friend’s house. Borrowing it, he roamed the streets of an unusually down-at-heel New York City, shooting the exuberant emergence of disco, the anxiety over the Son of Sam killings, the unrest that bubbled up during blackouts, and the countless other facets of urban life he’s continued to explore throughout his career. Encouraged by a film professor at Morehouse College, he then put in the hours to edit all this footage he’d simply grabbed for fun into a documentary called Last Hustle in Brooklyn. Nearly a decade later, he made his first feature, She’s Gotta Have It, an early entry in what would become the American indie film boom of the nineties.

Lee not only directed She’s Gotta Have It, but played one of its most memorable characters, a smooth-talking hustler of a b‑boy named Mars Blackmon. Mars cares about having the freshest gear, a trait he shares with the man who created him. This did not escape the notice of famous advertising agency Wieden+Kennedy; when a couple of their employees saw Lee’s performance as Mars, they knew they’d found the ideal pitchman for one of their client’s products. The company: Nike. The product: the Air Jordan. As surprised as anyone that such a major firm and the iconic athlete Michael Jordan would take a chance on a young director, Lee went ahead and shot the commercial above, which announced him as a new force in the late-1980s zeitgeist. To learn much more about this period of Lee’s career and its subsequent development, watch his episode of Inside the Actors Studio. Though considerably less of a motormouth than Mars Blackmon, Lee tells a compelling story, especially his own.

Related content:

40 Great Filmmakers Go Old School, Shoot Short Films with 100 Year Old Camera

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

If his goal is to be taken seriously, William Shatner hasn’t always been his own best friend. His covers of pop hits launched a whole mini-genre of unintentionally bad celebrity recordings.

To his credit, he made fun of himself to great effect on Boston Legal but followed that series up with a Broadway show It’s Shatner’s World, We Just Live In It, to mixed reviews.

But the man never quits. Earlier this month the Canadian Space Agency organized a Tweetup with Canadian astronaut Chris Hadfield, who is aboard the International Space Station orbiting the Earth. One space lover who participated was Shatner, who tweeted:

@Cmdr_Hadfield: “Are you tweeting from space? MBB”

A few hours later Hadfield, responded: “Yes, Standard Orbit, Captain. And we’re detecting signs of life on the surface.”

Shatner and Hadfield planned a longer conversation and it was hard to say who was more thrilled by the event: Trekkies the world over, Shatner, or Hadfield.

For about fifteen minutes today, with Houston Mission Control acting as galactic switchboard operator, the two chatted about the space program, the risks of living in space, and even some existential matters.

Right off the bat, Shatner asked Hadfield whether the fact that he had used a Russian vehicle to get up to the space station means that America is “falling behind” in its space program. The answer—long and upbeat—was, in a word, no.

Then Shatner asked Hadfield why he’d volunteered for the as-yet unscheduled mission to Mars.

“Isn’t that a fearful endeavor, fraught with enormous difficulty and danger?”

“Well you’ve taken a lot of risks in your life as well,” Hadfield replied.

He later went on to say that programs like Star Trek inspired him to study to become an astronaut.

“Going to Mars is inevitable,” Hadfield said, speaking into a floating, hand-held microphone, “just as sailing across the Atlantic or going to the moon. We take those visualized fantasies and turn them into realities.”

The view of Earth from his window on the Space Station, he added, is just like the view that Sulu and Chekhov had from the Starship Enterprise.

“It’s an enormous wonderful rolling Earth but all you have to do is flip yourself upside-down and the rest of the universe is under you.”

By the end of their chat, Hadfield had invited Shatner to visit him at his cabin and watch the satellites fly through the sky.

“You know those scenes in Boston Legal at the end of an episode when you were on the veranda drinking a whiskey and smoking a cigar, you ought to visit me in Northern Ontario. It’s a great place to talk about life.”

Related Content:

Leonard Nimoy Narrates Short Film About NASA’s Dawn: A Voyage to the Origins of the Solar System

William Shatner Narrates Space Shuttle Documentary

Star Trek Celebrities, William Shatner and Wil Wheaton, Narrate Mars Landing Videos for NASA

Kate Rix writes about digital media and education. Visit her at .

The tech-savviest among us may greet the news of a new BlackBerry phone with an exaggerated yawn, if that. But we have reasons not to dismiss the latest iteration of Research in Motion’s flagship product entirely. The Z10 launched to record early sales in the United Kindgom and Canada. Both the device and the fresh operating system that runs on it “represent a radical reinvention of the BlackBerry,” writes Wall Street Journal personal technology critc Walt Mossberg. “The hardware is decent and the user interface is logical and generally easy to use. I believe it has a chance of getting RIM back into the game.” Even so, building the product amounts to only half the battle; now the BlackBerry brand has to continue gaining, and manage to hold, customer interest. That’s where a certain master of gaining and holding interest named Neil Gaiman comes in.

Say what you will about their phones; Research in Motion’s marketing department has shown an uncommon degree of literary astuteness, at least by the standards of hardware makers. You may remember Douglas Coupland, for instance, turning up in advertisements for the BlackBerry Pearl back in 2006. But the company has recruited Gaiman—the English author of everything from novels like American Gods and Coraline to comic books like The Sandman to television series like Neverwhere to films like MirrorMask—for a more complicated undertaking than Coupland’s. Under the aegis of BlackBerry, Gaiman extends his collaboration-intensive work one domain further. A Calendar of Tales finds him sourcing ideas and visuals from the public in order to create “an amazing calendar showcasing your illustrations beside Neil’s stories.” The short video above recently appeared as the first in a series of episodes covering this storytelling project. Of this we’ll no doubt hear, see, and read much more before 2013’s actual calendar is out.

Related Content:

Download Free Short Stories by Neil Gaiman

Neil Gaiman Gives Graduates 10 Essential Tips for Working in the Arts

Neil Gaiman Gives Sage Advice to Aspiring Artists

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on literature, film, cities, Asia, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall.

For better or worse, Alain de Botton is the face of pop philosophy. He has advocated “religion for atheists” in a book of the same name (to the deep consternation of some atheists and the eloquent interest of others); he has distilled selected philosophical nuggets into self-help in his The Consolations of Philosophy; and most recently, he’s tackled a subject close to everybody’s heart (to put it charitably) in How to Think More About Sex. As a corollary to his intellectual interests in human betterment, de Botton also oversees The School of Life, a “cultural enterprise offering good ideas for everyday life” with a base in Central London and a colorful online presence. Many critics disdain de Botton’s shotgun approach to philosophy, but it gets people reading (not just his own books), and gets them talking, rather than just shouting at each other.

In addition to his publishing, de Botton is an accomplished and engaging speaker. Although himself a committed secularist, in his TED talks, he has posed some formidable challenges to the smug certainties of liberal secularism and the often brutal certainties of libertarian meritocracy. Apropos of the latter, in the talk above, de Botton takes on what he calls “job snobbery,” the dominant form of snobbery today, he says, and a global phenomenon. Certainly, we can all remember any number of times when the question “What do you do?” has either made us exhale with pride or feel like we might shrivel up and blow away. De Botton takes this common experience and draws from it some interesting inferences: for example, against the idea that we (one assumes he means Westerners) live in a materialistic society, de Botton posits that we primarily use material goods and career status not as ends in themselves but as the means to receive emotional rewards from those who choose how much love or respect to “spend” on us based on where we land in any social hierarchy.

Accordingly, de Botton asks us to see someone in a Ferrari not as greedy but as “incredibly vulnerable and in need of love” (he does not address other possible compensations of middle-aged men in overly-expensive cars). For de Botton, modern society turns the whole world into a school, where equals compete with each other relentlessly. But the problem with the analogy is that in the wider world, the admirable spirit of equality runs up against the realities of increasingly entrenched inequities. Our inability to see this is nurturned, de Botton points out, by an industry that sells us all the fiction that, with just enough know-how and gumption, anyone can become the next Mark Zuckerberg or Steve Jobs. But if this were true, of course, there would be hundreds of thousands of Zuckerbergs and Jobs.

For de Botton, when we believe that those who make it to the top do so only on merit, we also, in a callous way, believe those at the bottom deserve their place and should stay there—a belief that takes no account of the accidents of birth and the enormity of factors outside anyone’s control. This shift in thinking, he says—especially in the United States—gets reflected in a shift in language. Where in former times someone in tough circumstances might be called “unfortunate” or “down on their luck,” they are now more likely to be called “a loser,” a social condition that exacerbates feelings of personal failure and increases the numbers of suicides. The rest of de Botton’s richly observed talk lays out his philosophical and psychological alternatives to the irrational reasoning that makes everyone responsible for everything that happens to them. As a consequence of softening the harsh binary logic of success/failure, de Botton concludes, we can find greater meaning and happiness in the work we choose to do—because we love it, not because it buys us love.

Related Content:

Alain De Botton Turns His Philosophical Mind To Developing “Better Porn”

Alain de Botton’s Quest for The Perfect Home and Architectural Happiness

Socrates on TV, Courtesy of Alain de Botton (2000)

Josh Jones is a writer, editor, and musician based in Washington, DC. Follow him @jdmagness

What if the very thing that made you feel crazy happy also made you smarter? That’s the question underlying the work of the Institute for Centrifugal Research, where scientists believe that spinning people around at a sufficiently high G‑force will solve “even the trickiest challenges confronting mankind.”

We follow Dr. Nick Laslowicz, chief engineer, as he strolls through amusement parks, wearing a hard hat and taking notes, and describes the liberating power of spinning and the “mistake” of gravity.

The actor is terrific. Yes, The Centrifuge Brain Project is a joke. Laslowicz is just zany enough to be believable as a scientist whose research began in the 1970s. The sketches on the project’s website are fun too and director Till Nowak’s CGR rendering of the ride concepts are hilarious.

The culminating experiment features a ride that resembles a giant tropical plant. Riders enter a round car that rises slowly up, up, up and then takes off suddenly at incredibly high speed along one of the “branches.”

“Unpredictability is a key part of our work,” says Laslowicz. After the ride, he says, people described experiencing a “readjustment of key goals and life aspirations.” Though he later adds that he wouldn’t put his own children on one of his rides.

“These machines provide total freedom,” Laslowicz says, “cutting all connection to the world we live in: communication responsibility, weight. Everything is on hold when you’re being centrifuged.”

Related Content:

Miracle Mushrooms Power the Slums of Mumbai

Dark Side of the Moon: A Mockumentary on Stanley Kubrick and the Moon Landing Hoax

Kate Rix writes about digital media and education. Visit her work at .

Reg Presley, lead singer of the Sixties rock group The Troggs, died Monday at the age of 71. The Troggs (short for Troglodytes) are often mentioned as a major influence on the punk rock movement of the 1970s. They recorded a string of hits between 1966 and 1968, most notably “Wild Thing.” The Troggs are also remembered—much to the band’s chagrin—for one of the most notorious bootlegs ever: “The Troggs Tapes,” described by Uncut magazine as a “hilarious, 12-minute swearathon.”

The Troggs Tapes were recorded in London in 1970. The band was working on a song called “Tranquility,” but things weren’t going well, and the session degenerated into a foul-mouthed orgy of acrimony and recrimination. A copy of the recording somehow made it onto the bootleg market and became legendary. Saturday Night Live parodied the Troggs Tapes in a sketch with Bill Murray, John Belushi and others playing a group of frustrated medieval musicians who say the word “flogging” over and over. The tapes are also parodied in This is Spinal Tap, during the recording scene at the “Rainbow Trout Studios.” In a piece this week paying tribute to Reg Presley, the Telegraph music critic Neil McCormick writes:

Before the internet, The Troggs Tapes were hard to find, yet everyone seemed to know about them, an elusiveness that only added to their allure. I remember getting my hands on a copy in a Dublin flea market, then sitting aroud late at night with friends laughing ourselves silly at the inanity and palpable sense of frustration as the musicians fail to find a way to articulate and capture some sound idea, beyond the reach of either their language or their technical abilities.… In truth, it is the kind of conversation you can hear every day in recording studios all around the world, but there was something liberating and myth-busting about the experience of eavesdropping on these unguarded musicians at work.

You can listen to an abridged version of The Troggs Tapes above. To learn more about Reg Presley, you can read his fittingly unconventional obituary in The Telegraph. And to end things off on a positive note, we offer a glimpse of The Troggs when things were going considerably more smoothly, with the band performing “Wild Thing” in 1966:

Related Content:

8,976 Free Grateful Dead Concert Recordings in the Internet Archive, Explored by the New Yorker