What does David Byrne know about the history of the world in his new book A History of the World (in Dingbats)? As much as he knows about psycho killers, burning down houses, and “non-rational logic,” the subject of a show at New York’s Pace Gallery this past February featuring elaborate doodles Byrne calls “dingbats.” That is to say, he knows quite a lot about the history of the world. Or maybe, it hardly matters. “Burning Down the House” is not really about arson.

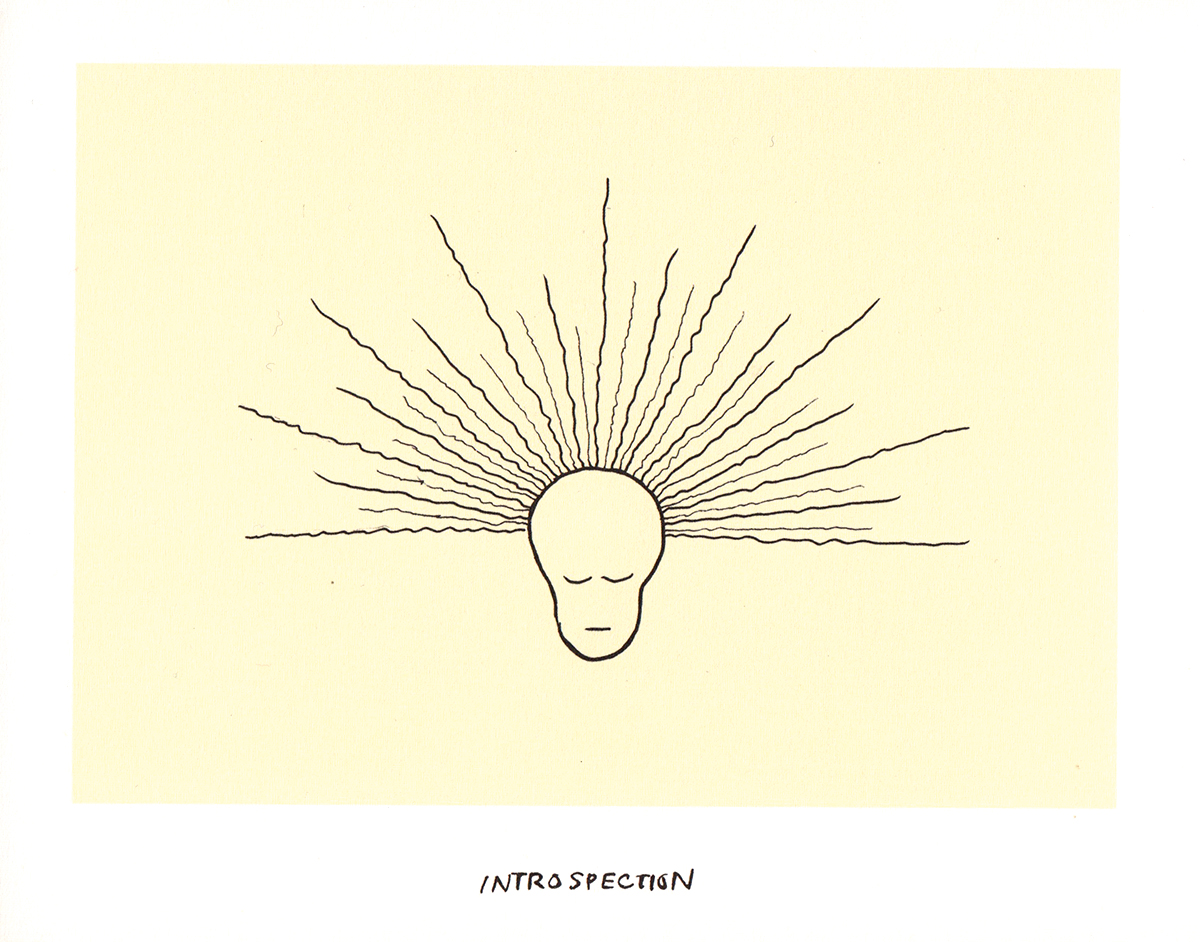

The new book presents us, instead of history, with a “cross between Codex Seraphinianus and E.E. Cumming’s little-known philosophical line drawings,” Maria Popova writes at The Marginalian. It is a work of the hopefulness of imagination; a statement about how “non-rational logic” can shape reality.

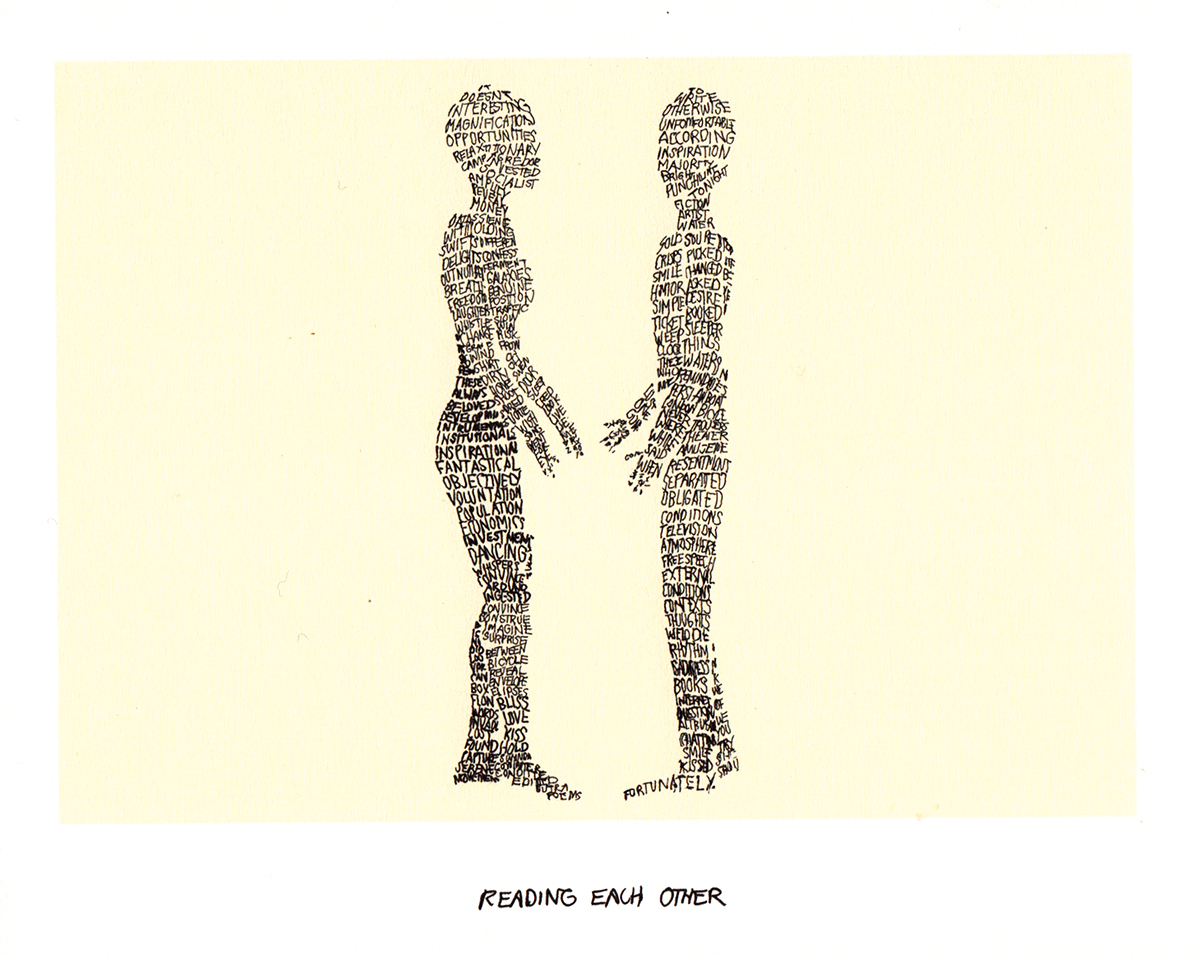

“The way things were,” Byrne writes, “the way we made things, it turns out, none of it was inevitable — none of it is the way things have to be.” Popova calls the project an “illustrated history of the possible future.”

“Created while under quarantine,” notes publisher Phaidon — the drawings “expand on the dingbat, a typographic ornament used to illuminate or break up blocks of text.” Byrne says he was inspired by the little illustrations in The New Yorker, though he took the concept much further. He writes text in each themed section that echoes the anxiety, contemplation, and strange excitement of life in lockdown: thoughts on what has been lost to us and on the life that might emerge in a world remade by a virus.

Byrne reminds us that history is “a story we tell ourselves.… These stories we tell ourselves about the world are not fixed.” Nor are the stories we each tell ourselves about who we are as individuals. These are ideas the artist has explored in projects ranging from his first book, 1995’s Strange Ritual, to his work with Luaka Bop, his world music label, to the album/Broadway show/feature film/picture book American Utopia — all projects concerned with expanding the boundaries of our shared human narrative.

Stories are lessons we send to ourselves — some remain vibrant and relevant while others are only useful for a moment. They serve myriad purposes that are often beyond our ken, for better or worse, and sometimes both at the same time.

How can we know when it’s time to let go, to move into a history of the future rather than the past? “Only you can find the way,” he writes, “in the city in your head.” It is our task to sift the stories that serve us from those that don’t, through critical reflection, the play of the imagination, and making new connections between our minds and bodies:

In the new world the rules have changed — or at least there is the possibility of change.

We can be different.

Order A History of the World (in Dingbats) here and see more of Byrne’s drawings at The Marginalian.

Related Content:

Watch a Very Nervous, 23-Year-Old David Byrne and Talking Heads Performing Live in NYC (1976)

David Byrne Answers the Internet’s Burning Questions About David Byrne

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness