Jazz instrumentalists who “play the changes” have learned to make improvisation look easy. In live performance, the audience shouldn’t see the years of study and practice behind what Willie Thomas calls at Jazz Everyone, “a system that combines the basic jazz language with the important music theory concepts” and at the same time “allows a player to focus on how the music fits the tune and not the chord symbols and scales that often incumber performance.”

That may seem like a wordy explanation, but Thomas is careful to explicate the cliché “play the changes” for maximum meaning, drawing on over forty years of experience himself learning the principle as a “useful tool for self expression through jazz music.” The idea of playing to the tune may seem fundamentally obvious, but the more one develops as a student, the farther away one can get from lived experience.

How might musicians apply ideals about ensemble playing to actual ensemble playing? For answers to this question, we might turn to jazz legend Chick Corea, member of Miles Davis’s band during the pathbreaking In a Silent Way and Bitches Brew sessions; player in and leader of more Grammy-winning ensembles than perhaps anyone else (he’s collected 23 awards so far); and “one of the jazz world’s most thoughtful and lucid champions.”

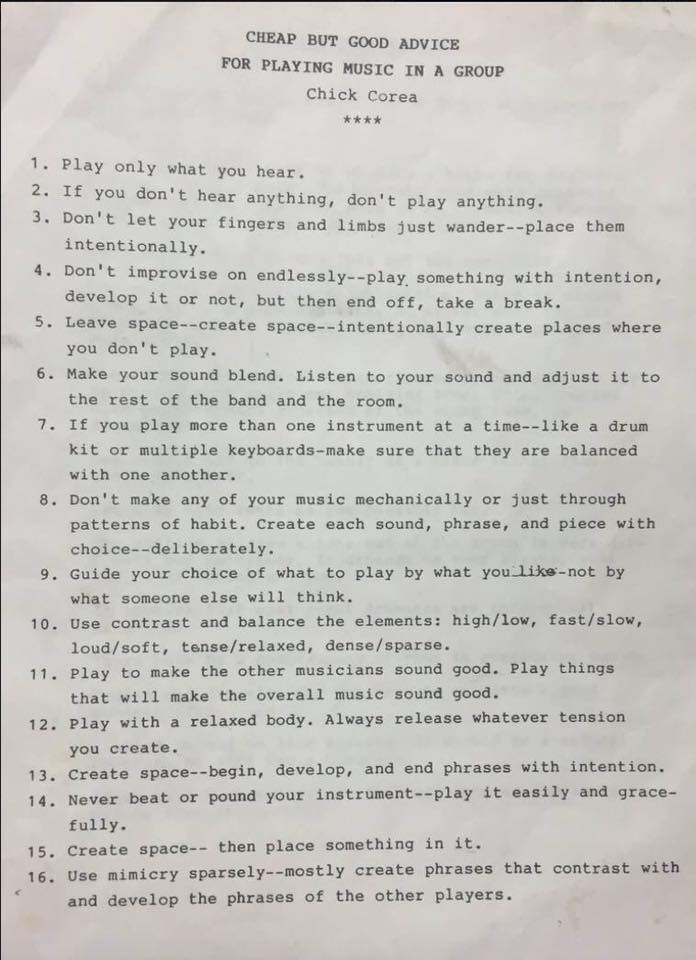

This description comes from a Christian Science Monitor write-up of Corea’s appearance in a two-hour Q&A session at Berklee College of Music in 1985, where the pianist and jazz fusion keyboard master had students pick up the typed handout above at the door. He begins with the simplest, but most important advice, “Play only what you hear,” then elaborates in 16 rules which you can read in full below.

Corea’s primary metaphor is architectural—performance, he says, is about creating spaces and tastefully filling them. Doing this well requires serious study and practice. Then it requires remembering some basic rules, or Chick Corea’s “Cheap But Good Advice for Playing Music in a Group.” My favorite: “always release whatever tension you create.” Like much of you we find here, it’s good all-around advice for every endeavor.

- Play only what you hear.

- If you don’t hear anything, don’t play anything.

- Don’t let your fingers and limbs just wander—place these intentionally.

- Don’t improvise on endlessly—play something with intention, develop it or not, but then end off, take a break.

- Leave space—create space—intentionally create places where you don’t play.

- Make your sound blend. Listen to your sound and adjust it to the rest of the band and the room.

- If you play more than one instrument at a time—like a drum kit or multiple keyboards—make sure that they are balanced with one another.

- Don’t make any of your music mechanically or just through patterns of habit. Create each sound, phrase, and piece with choice—deliberately.

- Guide your choice of what to play by what you like—not by what someone else will think.

- Use contrast and balance the elements: high/low, fast/slow, loud/soft, tense/relaxed, dense/sparse.

- Play to make the other musicians sound good. Play things that will make the overall music sound good.

- Play with a relaxed body. Always release whatever tension you create.

- Create space—begin, develop, and end phrases with intention.

- Never beat or pound your instrument—play it easily and gracefully.

- Create space—then place something in it.

- Use mimicry sparsely—mostly create phrases that contrast with and develop the phrases of the other players.

via Nate Chinen

Related Content:

Thelonious Monk’s 25 Tips for Musicians (1960)

John Coltrane Draws a Picture Illustrating the Mathematics of Music

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness