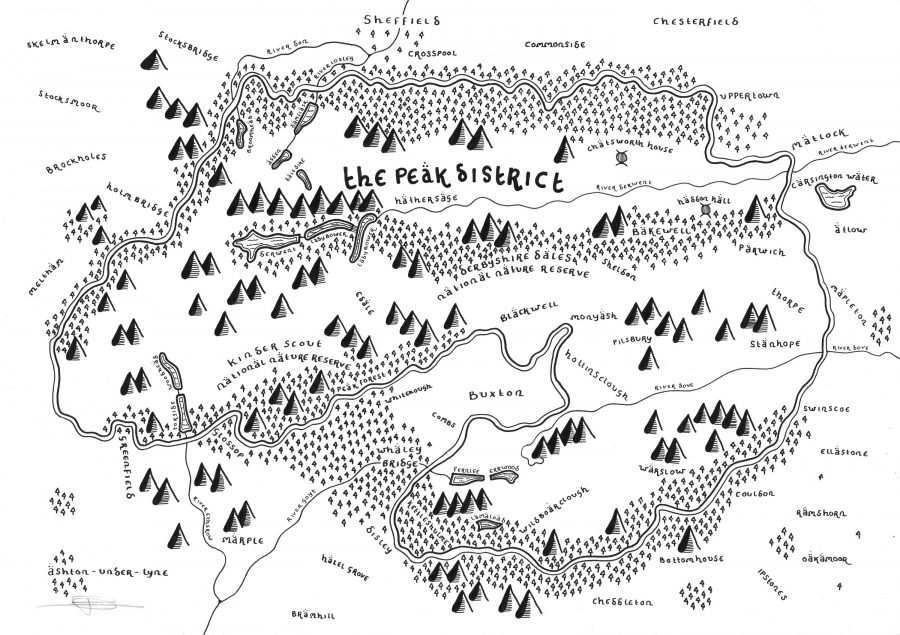

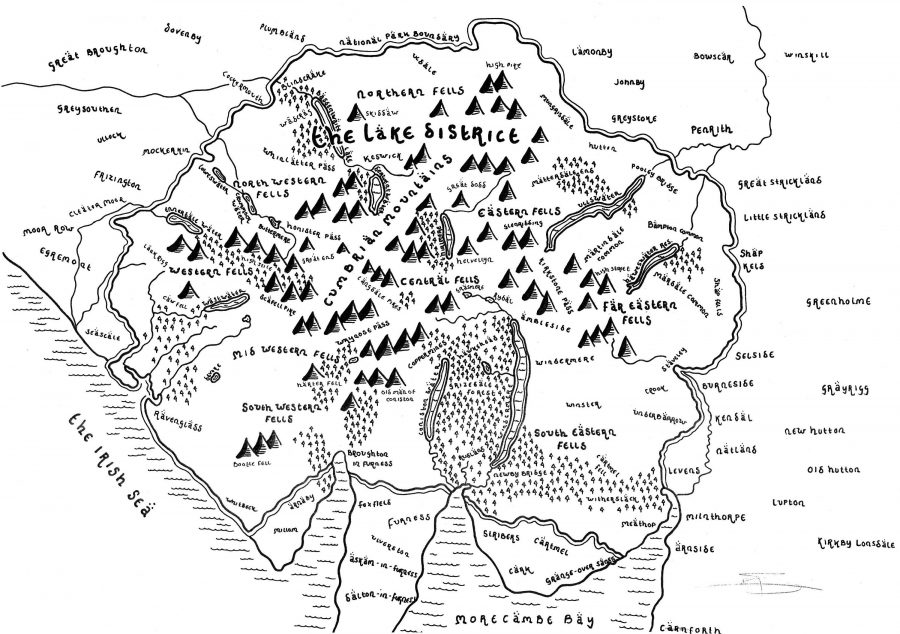

J.R.R. Tolkien imagined Middle-Earth by drawing not just from far-flung lands and old myths but the English landscape all around him. Of course, everyone who reads The Lord of the Rings trilogy, let alone the related books written by Tolkien as well as his followers, has their own way of envisioning the place, and those who go especially deep may even start seeing their own, real environments as versions of Middle-Earth. That seems to have happened in the case of Dan Bell, an English artist who maps his homeland’s national parks in an artistic style similar to the one in which Tolkien rendered Middle-Earth.

Bell “began reading Tolkien’s books when he was 11 or 12 years old, and fell in love with them,” writes The Verge’s Andrew Liptak. “In particular, he was struck by Tolkien’s maps.” To start, he “works from an open source Ordnance Survey map, and begins drawing by hand,” adding in such additional details, not always found in most national parks, as “forests, Hobbit holes, towers, and castles.” Having so adapted the national parks of the United Kindgom “as well as places like Oxford, London, Yellowstone National Park, and George R.R. Martin’s Westeros,” he’s made them available for purchase on his site.

Most of us who first encounter The Lord of the Rings at the age Bell did have surely wished, if only for a moment or two, that we could live in Middle-Earth ourselves. Bell’s maps remind us that places like Middle-Earth always come in some way from, and resonate on some level with, the real Earth on which we have no choice but to live. Much like how the settings of science fiction stories, no matter how technologically amplified or culturally twisted and turned, always reflect the time of the story’s composition, thoroughly realized fantasy realms, no matter how fantastical — how many hobbit-holes, castles, or Eyes of Sauron with which they may be dotted — are never 100 percent made up. Just ask the tourist industry of New Zealand.

Enter Bell’s map collection here.

via The Verge

Related Content:

Map of Middle-Earth Annotated by Tolkien Found in a Copy of Lord of the Rings

110 Drawings and Paintings by J.R.R. Tolkien: Of Middle-Earth and Beyond

The Only Drawing from Maurice Sendak’s Short-Lived Attempt to Illustrate The Hobbit

Soviet-Era Illustrations Of J. R. R. Tolkien’s The Hobbit (1976)

226 Ansel Adams Photographs of Great American National Parks Are Now Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.