Today the word “alchemy” seems used primarily to label a variety of crackpot pursuits, with their bogus premises and impossible promises. To the extent that alchemists long strove to turn lead miraculously into gold, that sounds like a fair enough charge, but the field of alchemy as a whole, whose history runs from Hellenistic Egypt to the 18th century (with a revival in the 19th), chalked up a few lasting, reality-based accomplishments as well. Take, for instance, medieval illuminated manuscripts: without alchemy, they wouldn’t have the vivid and varied color palettes that continue to enrich our own vision of that era.

Many of the illuminators’ most brilliant pigments “didn’t come straight from nature but were made through alchemy,” says the video from the Getty above, produced to accompany the museum’s exhibition “The Alchemy of Color in Medieval Manuscripts.”

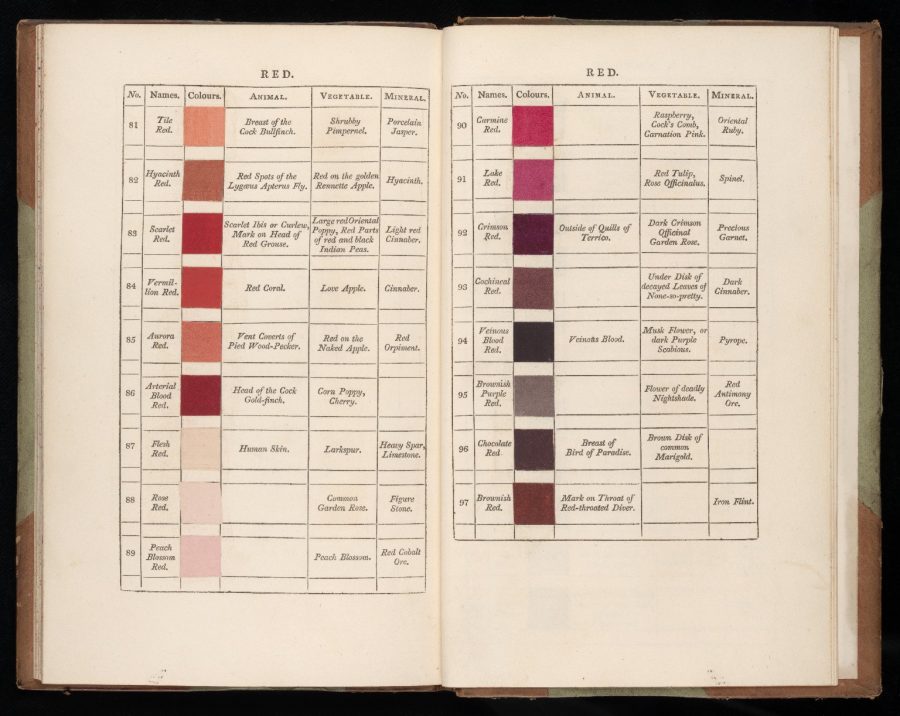

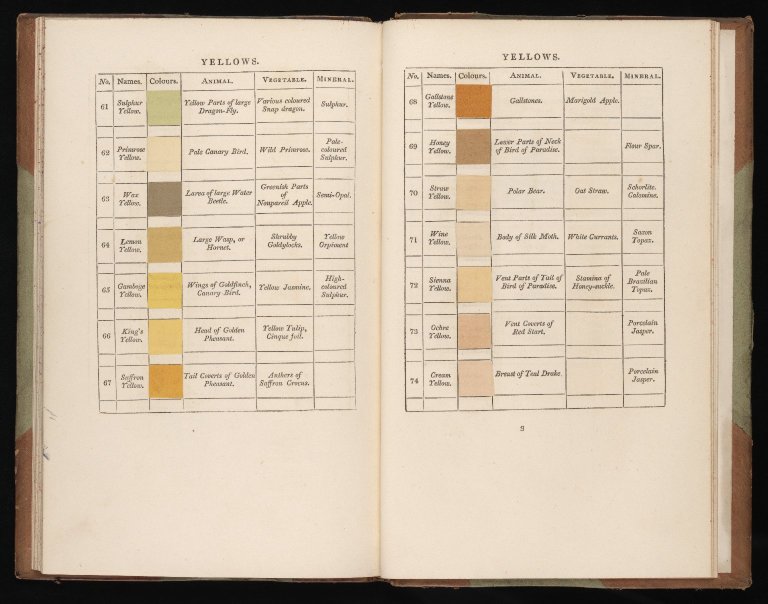

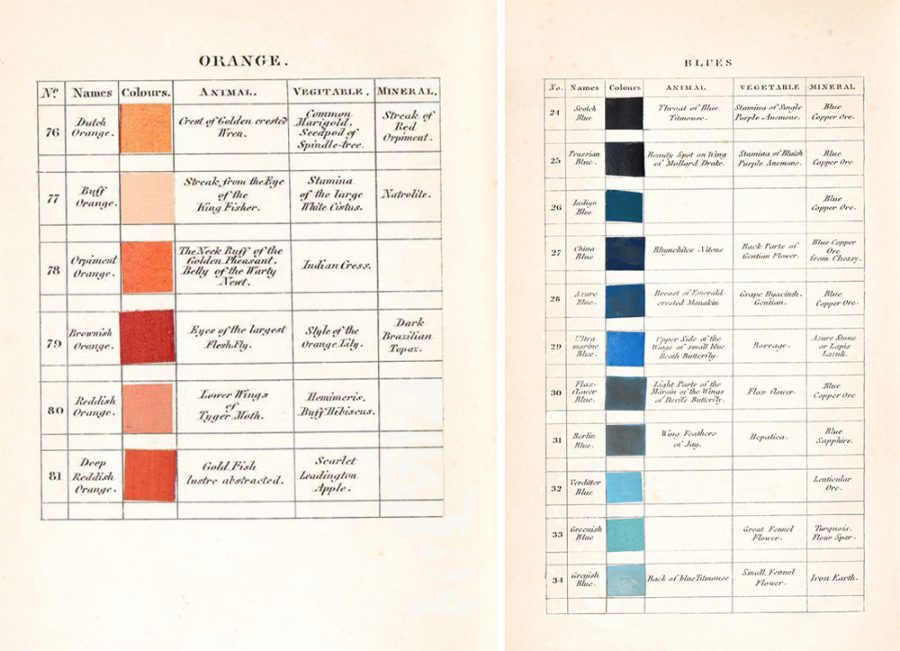

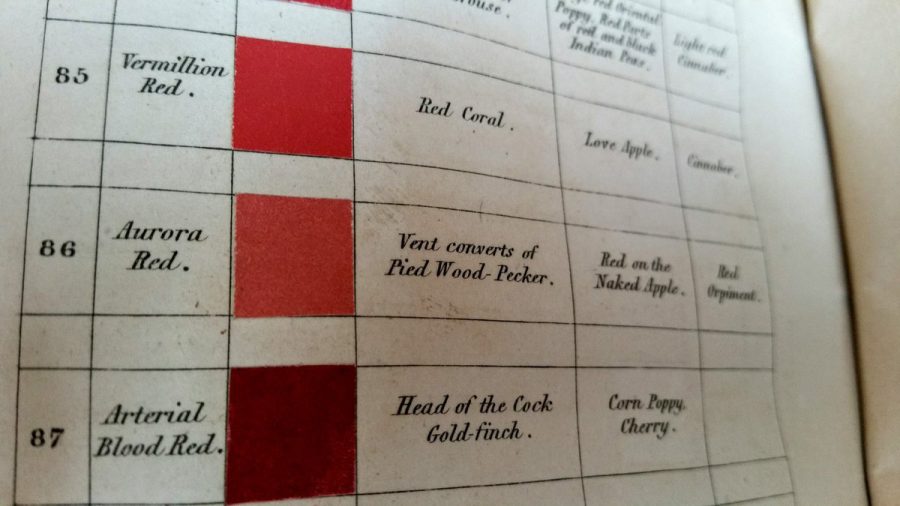

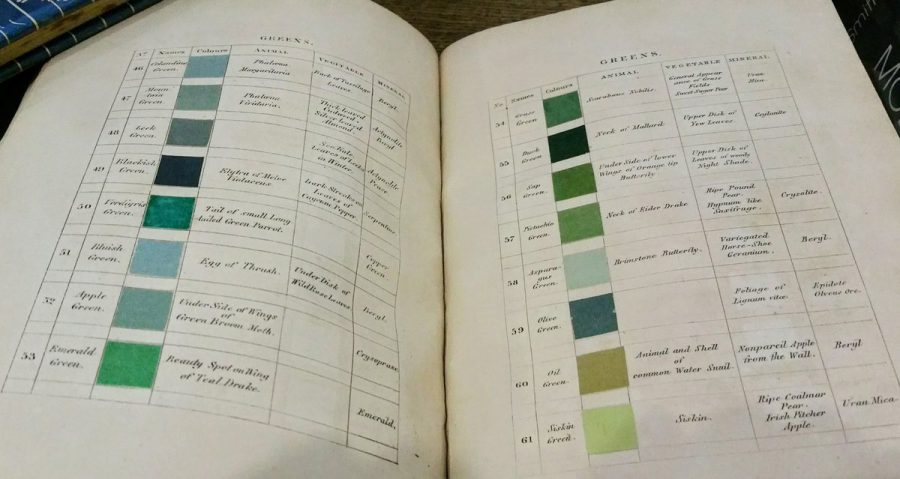

Alchemists “explored how materials interacted and transformed,” and “discovering paint colors was a practical outcome.” The colors they developed included “mosaic gold,” a fusion of tin and sulfur; verdigris, “made by exposing copper to fumes of vinegar, wine, or even urine”; and vermillion, a mixture of sulfur and mercury that made a brilliant red “associated with chemical change and with alchemy itself.”

The very nature of books, specifically the fact that they spend most of the time closed, has performed a degree of inadvertent preservation of illuminated manuscripts, keeping their alchemical colors relatively bold and deep. (Although, as the Getty video notes, some pigments such as verdigris have a tendency to eat through the paper — one somehow wants to blame the urine.) Still, that hardly means that preservationists have nothing to do where illuminated manuscripts are concerned: keeping the windows they provide onto the histories of art, the book, and humanity clear takes work, some of it based on an ever-improving understanding of alchemy. Lead may never turn into gold, but these centuries-old illuminated manuscripts may survive centuries into the future, a fact that seems not entirely un-miraculous itself.

Related Content:

1,600-Year-Old Illuminated Manuscript of the Aeneid Digitized & Put Online by The Vatican

Wonderfully Weird & Ingenious Medieval Books

1,000-Year-Old Illustrated Guide to the Medicinal Use of Plants Now Digitized & Put Online

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.