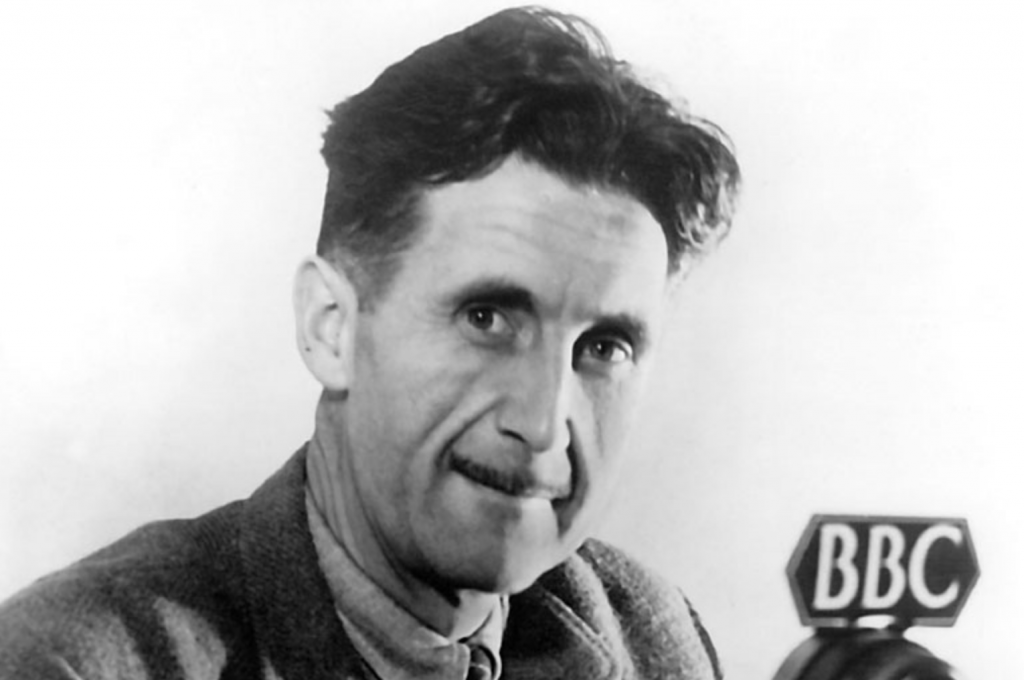

Image by BBC, via Wikimedia Commons

Everyone should learn to write well, I used to tell students in Composition classes, and I believed it. To write well, in a certain sense, is to become a better thinker. But writing differs from writing, perhaps, in the same way that walking the dog differs from hiking the Appalachian trail. There are levels of difficulty. How badly do you need to say something that no one else can—or wants to—say? How badly do you need to push this thing you’ve said into the world?

These are separate questions. Some writers really do write for themselves, some write for money, though they might also write for free. Some write as a means to other ends, and some require, at all times, an audience. It may be a sexual compulsion or an animal reflex or the only way to get one’s mind right. Or some combination of the above. As a Jesuit scholar I once knew would say, “I’ve never met a motive that wasn’t mixed.” Given the difficulty of discerning why anyone does anything, there could be as many mixed motives as there are writers.

That said, I tend to think that every writer who reads George Orwell’s essay “Why I Write” sees themselves in some part of his description of his early life. “I was somewhat lonely,” he tells us, “and I soon developed disagreeable mannerisms which made me unpopular throughout my schooldays. I had the lonely child’s habit of making up stories and holding conversations with imaginary persons, and I think from the start my literary ambitions were mixed up with the feeling of being isolated and undervalued.”

Maybe everyone has such feelings, but again it is a question of degree. Given Orwell’s keen understanding of the writer’s mind from the inside out, and his diligent pursuit of his work through the most trying times, we might be inclined to give him a hearing when he claims, “there are four great motives for writing, at any rate for writing prose.” Orwell allows that these motives will be mixed, existing “in different degrees in every writer, and in any one writer the proportions will vary from time to time, according to the atmosphere in which he is living.”

But no one whom we might call a writer, Orwell suggests, writes solely for utility or money. The rewards are too peculiarly psychological, as are the pains. And the pleasures too otherworldly and practically useless. Orwell begins with one of those psychological compensations, fame, then proceeds to pleasure, then to duty to posterity and, finally, to persuasion; the four reasons, he says:

(i) Sheer egoism. Desire to seem clever, to be talked about, to be remembered after death, to get your own back on the grown-ups who snubbed you in childhood, etc., etc. It is humbug to pretend this is not a motive, and a strong one. Writers share this characteristic with scientists, artists, politicians, lawyers, soldiers, successful businessmen — in short, with the whole top crust of humanity. The great mass of human beings are not acutely selfish. After the age of about thirty they almost abandon the sense of being individuals at all — and live chiefly for others, or are simply smothered under drudgery. But there is also the minority of gifted, willful people who are determined to live their own lives to the end, and writers belong in this class. Serious writers, I should say, are on the whole more vain and self-centered than journalists, though less interested in money.

(ii) Aesthetic enthusiasm. Perception of beauty in the external world, or, on the other hand, in words and their right arrangement. Pleasure in the impact of one sound on another, in the firmness of good prose or the rhythm of a good story. Desire to share an experience which one feels is valuable and ought not to be missed. The aesthetic motive is very feeble in a lot of writers, but even a pamphleteer or writer of textbooks will have pet words and phrases which appeal to him for non-utilitarian reasons; or he may feel strongly about typography, width of margins, etc. Above the level of a railway guide, no book is quite free from aesthetic considerations.

(iii) Historical impulse. Desire to see things as they are, to find out true facts and store them up for the use of posterity.

(iv) Political purpose. — Using the word ‘political’ in the widest possible sense. Desire to push the world in a certain direction, to alter other peoples’ idea of the kind of society that they should strive after. Once again, no book is genuinely free from political bias. The opinion that art should have nothing to do with politics is itself a political attitude.

Surely, someone will suggest others, but it may be that other reasons would still fall into these categories. Neither are these motives consonant, “they must war with one another,” Orwell writes, and readers tend to egg the conflict on, declaring historical memoirs as products of pure egotism or turning their noses up at overly “political” novels.

Surprisingly, Orwell reveals that he might have done the same, had not circumstances forced his hand. “In a peaceful age I might have written ornate or merely descriptive books, and might have remained almost unaware of my political loyalties,” he says. But who lives in a peaceful age? In any case, we might wonder if he is being completely honest. “What I have most wanted to do throughout the past ten years is to make political writing into an art. My starting point is always a feeling of partisanship, a sense of injustice.”

Orwell admits that his task “is not easy,” and he offers unsparing examples of times when his writing has moved too far toward one end of the spectrum on which he situates himself. What is instructive about his framework for understanding his motivations, however, is that he has the tools to self-correct. Such self-knowledge can serve anyone in good stead. For the writer, who is compelled to reveal themselves over and over, it may be essential.

You can purchase your copy of Orwell’s “Why I Write” here.

Related Content:

George Orwell Explains in a Revealing 1944 Letter Why He’d Write 1984

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness