Patti Smith has always aligned herself with artists who were outsiders and experimentalists in their time, but who have since moved to the center of the culture, where they are often reduced to a few biographical notes. Arthur Rimbaud, Virginia Woolf, William Blake…. As much motivated by art and poetry as by the aggression of rock and roll, Smith’s 1975 debut album reached out to people on the margins of popular culture. “I was speaking to the disenfranchised, to people outside society, people like myself,” she says, “I didn’t know these people, but I knew they were out there. I think Horses did what I hoped it would do. It spoke to the people who needed to hear it.”

It’s hard to imagine who those people were. In the process of its canonization, unfortunately, punk has come to be seen as a rejection of culture, a form of anti-art. But Smith’s amalgam of loose, rangy garage rock brims with artiness, making it “the natural link between the Velvet Underground and the Ramones,” writes Jillian Mapes at Pitchfork, “in the continuum of downtown New York rock.” Pitchfork situates Smith’s first record at the top of their “Story of Feminist Punk in 33 Songs,” more “influential in its attitude” perhaps than in its particular style. “Her presence at the forefront of the scene was a statement in itself,” but a statement of what, exactly?

One of the fascinating things about Smith was her subversion of gendered expectations and identities. In the epic medley “Land: Horses/Land of a Thousand Dances/La Mar (De),” her protagonist is an abused boy named Johnny. She slides into a sinuous androgynous vamp, portraying a “sweet young thing. Humping on a parking meter” with the dangerous sexual energy she appropriated from idols like Mick Jagger. Yet in her twist on the performance of a classically masculine sexuality, vulnerability becomes dangerous, survival a fierce act of defiance: “Life is filled with holes,” she sings, “Johnny’s laying there, his sperm coffin, angel looks down at him and says, ‘Oh, pretty boy, can’t you show me nothing but surrender?”

Johnny shows the angel, in a gritty West Side Story-like scene that illustrates the razor edges at the heart of Smith’s musical poetry. He gets up, “takes off his leather jacket, taped to his chest there’s the answer, you got pen knives and jack knives and switchblades preferred, switchblades preferred.” Horses is so foundational—to punk rock, feminist punk, and a whole host of other countercultural terms that didn’t exist in 1975—that it’s unfair to expect Smith’s subsequent albums to reach the same heights and depths with the same raw, unbridled energy. Her 1976 follow-up, Radio Ethiopia, disappointed many critics and fans, though it has since become a classic.

As William Ruhlmann writes at Allmusic, “her band encountered the same development problem the punks would—as they learned their craft and competence set in, they lost some of the unself-consciousness that had made their music so appealing.” The music may have become mannered, but Smith was a profoundly self-conscious artist from the start, and would remain so, exploring in album after album her sense of herself as the product of her influences, whom she always speaks of as though they are close personal friends or even aspects of her own mind. Who is Patti Smith speaking to? Her heroes, her friends, her family, her various selves, the men and women who form a community of voices in her work.

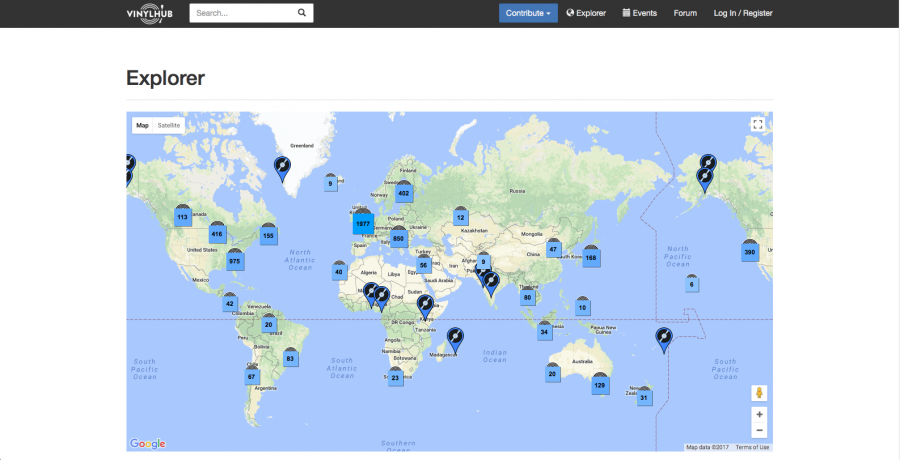

We get to listen in on those conversations, and we find ourselves torn out of the familiar through Smith’s detournment of classic rock swagger and beatnik poses. You can hear her many voices develop, refine, and sometimes stumble into creative missteps that are far more interesting than so many artists’ successes in the playlist above, a complete 13-hour chronological discography (save some rarities and live albums that aren’t on Spotify) of Smith’s work—a lifetime of what her father called a “development of the country of the mind” as she remarked in a 1976 interview. “He believed that the mind was a country, and you had to develop it, you had to build and build and build the mind.”

These are not the kinds of sentiments we might expect to hear from the so-called “Godmother of Punk.” Which might speak to how little we understand about what Smith and her motley compatriots were up to amid the grime and squalor of mid-seventies downtown New York.

Related Content:

33 Songs That Document the History of Feminist Punk (1975–2015): A Playlist Curated by Pitchfork

Hear Patti Smith Read the Poetry that Would Become Horses: A Reading of 14 Poems at Columbia University, 1975

Patti Smith’s New Haunting Tribute to Nico: Hear Three Tracks

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness