Just about twenty years ago, on July 9, 1995, the Grateful Dead played their last show with Jerry Garcia. Neither the fans, nor the band knew this would be so, but anyone paying attention could have seen it coming. Garcia’s cocaine and heroin use had long dominated his life; despite interventions by his bandmates, a few stints in rehab, a diabetic coma, and the death of keyboardist Brent Mydland, the singer and guitarist continued to relapse. Exactly one month after that final concert, he died of a heart attack.

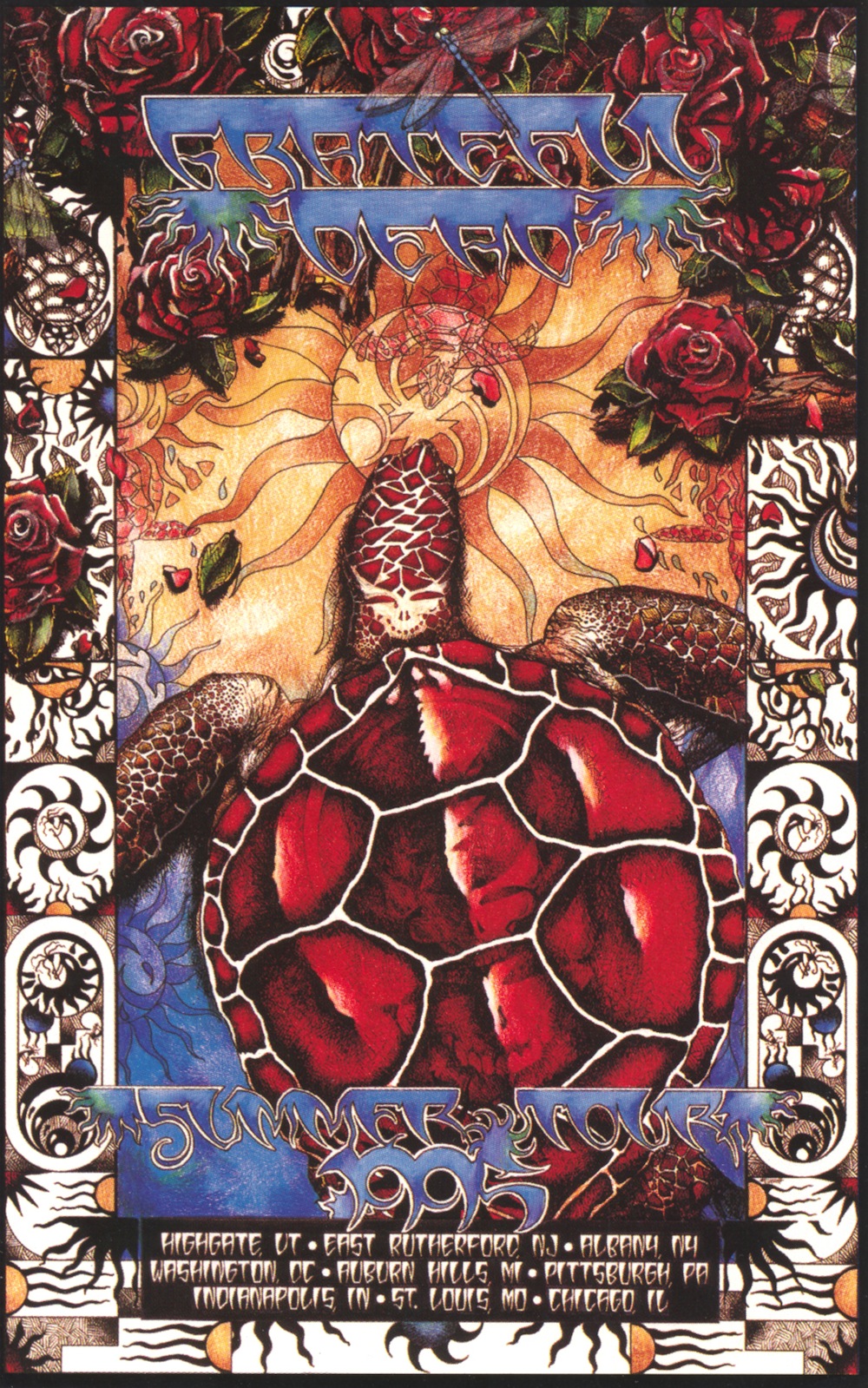

And what a poignant show it was. (See the tour poster above, hear the entire set below, and see a setlist here), opening with the band’s comeback hit “Touch of Grey” and closing with a fireworks display set to Hendrix’s “Star Spangled Banner.”

Garcia sounds frail, his voice a bit thin and ragged, and the lyrics—penned by Robert Hunter—strike a painfully ironic note: “I will get by… I will survive.” Just last night, twenty years after that moment, fans once again said goodbye to the Dead, as they played their last of three final concerts without Jerry at Chicago’s Soldier’s Field, the same venue where Garcia last sang “Touch of Grey“ ‘s fateful words.

The Grateful Dead’s official output may have been uneven at times, marred by excess and tragedy, but the band’s words remained consistently inspired and inspiring, each song a poetic vignette filled with oblique references and witty, heartfelt turns of phrase. We mostly have Robert Hunter to thank for those hundreds of memorable verses. An accomplished poet and translator of Rainer Maria Rilke’s Duino Elegies and Sonnets to Orpheus, Hunter served, writes Rolling Stone, as the band’s “primary in-house poet.” In a rare and moving interview with the magazine, the reclusive writer muses on his former role, and hedges on the meaning of his songs: “I’m open to questions about interpretation, but I generally skate around my answers because I don’t want to put those songs in a box.”

Hunter’s reluctance to interpret his lyrics hasn’t stopped fans and scholars of the Dead from doing so. There have been university exhibits and academic conferences devoted to the Grateful Dead. And true students of the band can study the many literary references and allusions in their songwriting with The Annotated Grateful Dead Lyrics, an online project begun in 1995 by UC Santa Cruz Research Associate David Dodd, and turned into a book in 2005. The extensive hypertext version of the project includes editorial footnotes explaining each song’s references, with sources. Also included in these glosses are “notes from readers,” who weigh in with their own speculations and scholarly addenda.

If you have any doubt about just how steeped in poetic history the pre-eminent hippie band’s catalog is, see for example the annotated “Terrapin Station,” a song that reaches back to Homer and alludes to Lewis Carroll, William Blake, Plato, and T.S. Eliot. Or, so, at least, say Dodd and his readers, though some of their interpretations may seem a bit tenuous. Hunter himself told Rolling Stone, “people think I have a lot more intention at what I do because it sounds very focused and intentional. Sometimes I just write the next line that occurs to me, and then I stand back and look at it and say, ‘This looks like it works.’ ” But just because a poet isn’t consciously quoting Homer doesn’t mean he isn’t, especially a poet as densely allusive as Robert Hunter.

Take, for example, “Uncle John’s Band,” which contains the line “Ain’t no time to hate.” One reader, Aaron Bibb, points us toward these lines of Emily Dickinson:

I had no time to Hate—

Because

The Grave would hinder Me—

And Life was not so

Ample I

Could finish—Enmity—

Woven throughout the song are references to American poetry and folk music—from Robert Frost’s “Fire and Ice,” to the Gadsden Flag, to an Appalachian rag. Another of the band’s most popular songs, “Friend of the Devil,” cribs its title and chorus from American folk singer Bill Morrissey’s song “Car and Driver”—and also references Don McLean’s “American Pie.” Drawing as much on the Western literary canon as on the American songbook, Hunter’s writing situates the Dead’s Americana in a tradition stretching over centuries and continents, giving their music depth and complexity few other rock bands can claim.

The online annotated Grateful Dead also includes “Thematic Essays,” a bibliography and “bibliography of songbooks,” films and videos, and discographies for the band and each core member. There may be no more exhaustive a reference for the band’s output contained all in one place, though readers of this post may know of comparable guides in the vast sea of Grateful Dead commentary and compendiums online, in print, and on tape. The band may have played its last show twenty years ago, and again just last night without its beloved leader, but the proliferating, serious study of their songcraft and lyrical genius shows us that they will, indeed, survive.

Related Content:

The Grateful Dead’s “Ripple” Played by Musicians Around the World

10,173 Free Grateful Dead Concert Recordings in the Internet Archive

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness