Thomas Hardy—architect, poet, and writer (above)—gave us the fierce, stormy romance Far From the Madding Crowd, currently impressing critics in a film adaptation by Thomas Vinterberg. He also gave us Tess of the D’Urbervilles, The Return of the Native, and Jude the Obscure, books whose persistently grim outlook might make them too depressing by far were it not for Hardy’s engrossing prose, unforgettable characterization, and, perhaps most importantly, unshakable sense of place. Hardy set most of his novels in a region he called Wessex, which—much like William Faulkner’s Yoknapatawpha—is a thinly fictionalized recreation of his rural hometown of Dorchester and its surrounding counties.

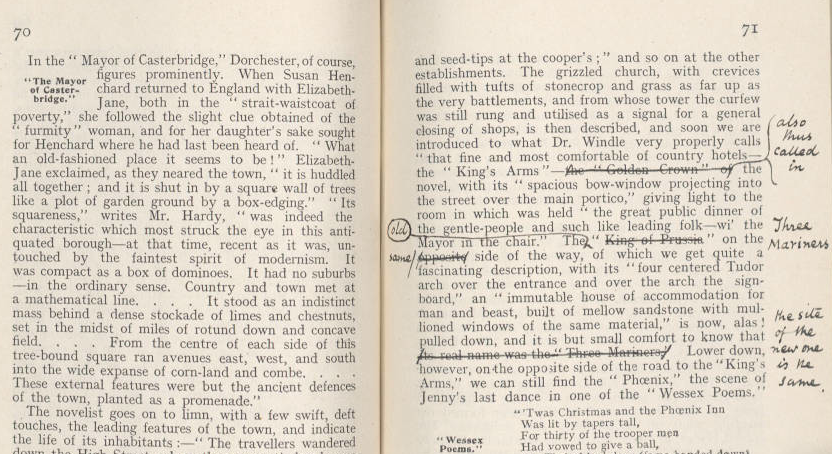

Now, thanks to the University of Texas at Austin’s Harry Ransom Center, we can learn all about this ancient region in South West England, and Hardy’s transmutation of it, through Hardy’s own proof copy of a 1905 book by Frank R. Heath called Dorchester (Dorset) and its Surroundings, with revisions in Hardy’s hand. In the excerpt above, for example, from page 36 of this scholarly work, the author discusses Hardy’s use of Dorchester in The Mayor of Casterbridge and the so-called “Wessex Poems.” In the margins on the right, we see Hardy’s corrections and glosses. Though this may not seem the most exciting piece of Hardy memorabilia, for students of the author and his investment in a rural corner of England, it is indeed a treasure.

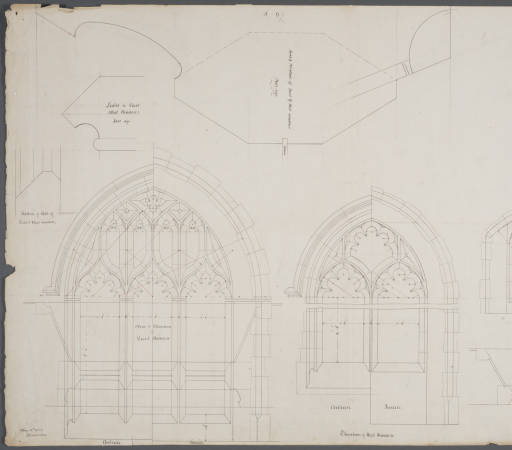

The Hardy archive also contains scans of the author’s correspondence, manuscripts and signed typescripts, and architectural drawings, like that of St. Juliot’s Church in Cornwall, above. This extensive digital Hardy collection is but one of many housed in the Ransom Center’s Project Reveal, an acronym for “Read and View English & American Literature.” Read and view you can indeed, through the intimacy of first drafts, manuscripts, personal writing, and other ephemera.

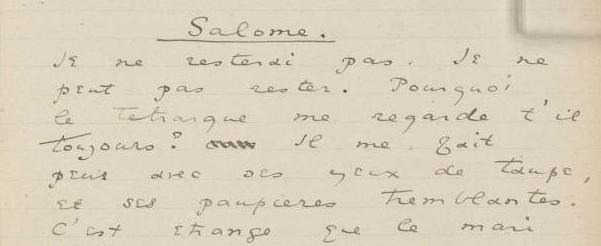

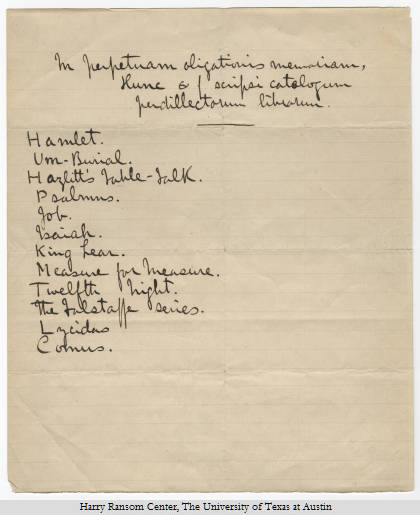

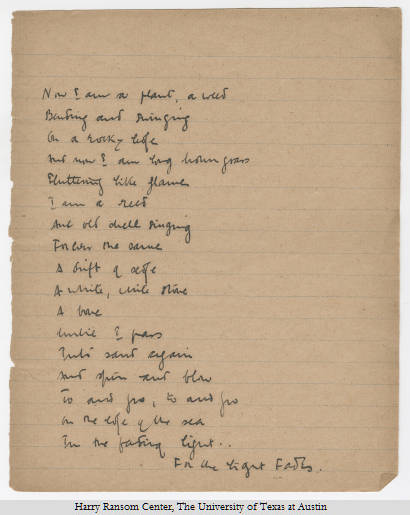

See, for example, a handwritten draft of Oscar Wilde’s Salome, in French, (excerpt above). Below, we have a handwritten list of Robert Louis Stevenson’s favorite books, and further down, a manuscript draft of Katherine Mansfield’s “Now I am a plant, a weed” from her personal poetry notebook.

Other authors included in the Project Reveal archive include Charlotte Perkins Gilman, Hart Crane, Henry James, Joseph Conrad, and William Thackeray. The project, writes the Ransom Center in a press release, generated more than 22,000 high-resolution images, available for use by anyone for any purpose without restriction or fees” (but with attribution). The literary storehouse on display here only adds to an already essential collection of artifacts the Ransom Center houses, such as the papers of Gabriel Garcia Marquez, syllabi, annotated books, and manuscripts from David Foster Wallace, scrapbooks of Harry Houdini, and the first known photograph ever taken. See a complete list of contents of the Ransom Center’s Digital Collections here, and learn more about this amazing library in the heart of Texas at their main site.

Related Content:

Yale Launches an Archive of 170,000 Photographs Documenting the Great Depression

Literary Remains of Gabriel García Márquez Will Rest in Texas

David Foster Wallace’s Love of Language Revealed by the Books in His Personal Library

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness