I watched Star Wars for the first time in 1977 at the tender age of four. And like a lot of people in my generation and younger, that first time was a major, formative experience in my life. I got all the toys. I fantasized about being Han Solo. And during the summer of ’83, I blew my allowance by watching Return of the Jedi every day for a week in the theater. George Lucas’ epic space opera is the reason why I spent a lifetime watching, making and writing about movies. And if you asked any movie critic, fan or filmmaker who grew up in the ‘80s, they will probably tell you a similar story.

Over the years though, Lucas succumbed to the dark side of the Force. His prequel trilogy, starting with truly god awful The Phantom Menace (1999), is as visually overstuffed as it is cinematically inert. (Somewhere, there’s a dissertation to be written about how widespread feelings of betrayal from the prequels psychically prepared America for the anxiety and disappointments of the Bush administration.)

Worse, fans who want to console themselves by watching Star Wars as they remember seeing it back in the ‘80s are out of luck. Lucas has been quietly butchering the original movies by adding CGI, sound effects and even whole characters – like (gag) Jar Jar Binks — to successive special edition updates. The problem is these updated versions feel bifurcated. It’s as if two different movies with two different aesthetics were clumsily stitched together. Lucas’ spare, muscular compositions in the original movie sit uneasily next to its cartoony, over-wrought additions. Yet this Frankenstein version is the one that Lucas insists you watch. The original cut is just plain not for sale. Lucas even refused to give the National Film Registry the 1977 cut of Star Wars for future preservation. “It’s like this is the movie I wanted it to be,” said Lucas in an interview in 2004, “and I’m sorry if you saw half a completed film and fell in love with it, but I want it to be the way I want it to be.”

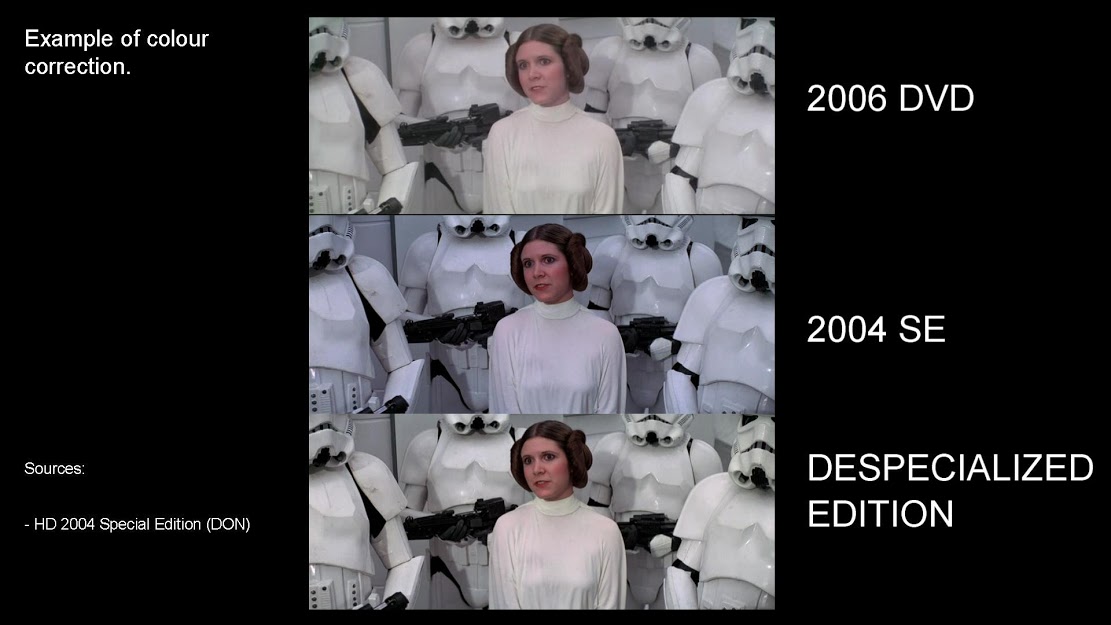

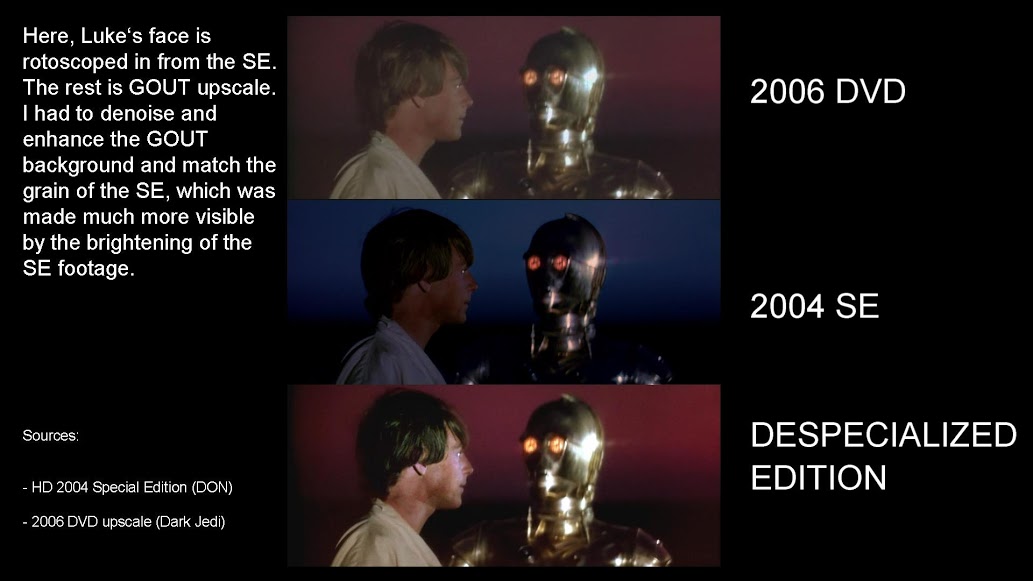

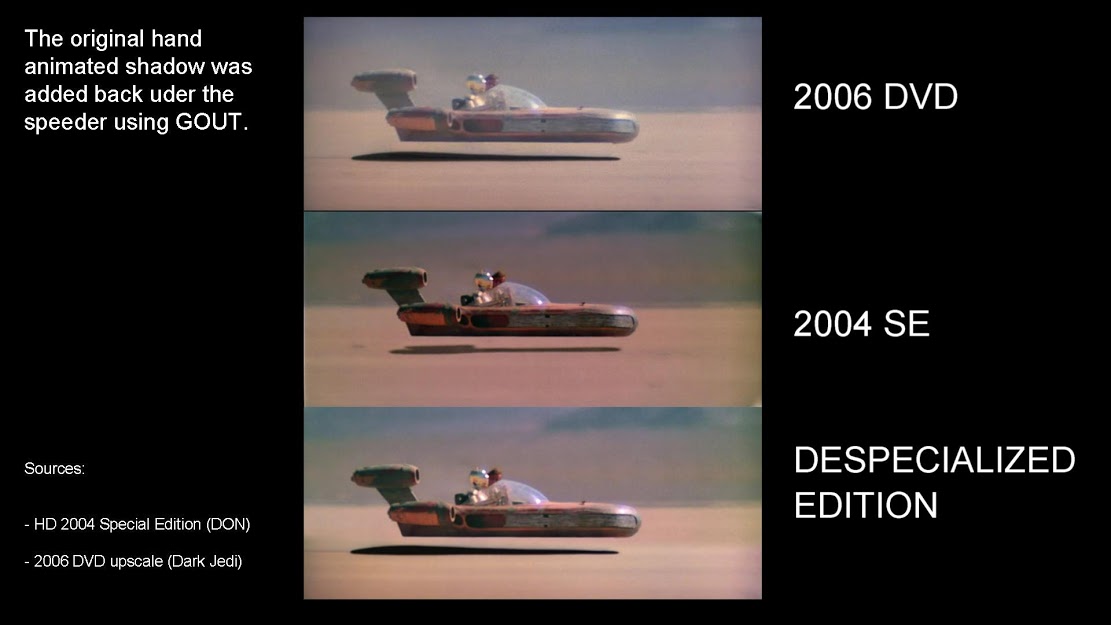

Thankfully, hardcore Star Wars fans are telling Lucas, respectfully, to go cram it. As Rose Eveleth in The Atlantic reports, a dedicated online community has set out to create a “despecialized” edition of Star Wars that strips away all of Lucas’s digital nonsense and restores the movie to its original 1977 state. The de facto leader of this movement is Petr Harmy, a 25-year-old guy from the Czech Republic who with the help of a legion of technically savvy film nerds has pieced together footage from existing prints and older DVD releases to create the Despecialized Edition v. 2.5. (Directions on where you can locate it are here.) Above Harmy talks in detail about how he accomplished this feat. And below you can see some side-by-side comparisons. More can be found on Petr Harmy’s page. Finally, in the comments section below, Harmy also points us toward pages with Despecialized stills for Star Wars and The Empire Strikes Back.

Via The Atlantic

Related Content:

How Star Wars Borrowed From Akira Kurosawa’s Great Samurai Films

Freiheit, George Lucas’ Short Student Film About a Fatal Run from Communism (1966)

Watch the Very First Trailers for Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back & Return of the Jedi (1976–83)

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers Break Down Star Wars as an Epic, Universal Myth

Hundreds of Fans Collectively Remade Star Wars; Now They Remake The Empire Strikes Back

Jonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow. And check out his blog Veeptopus, featuring one new drawing of a vice president with an octopus on his head daily.