Back in 1977, San Francisco filmmaker Ernie Fosselius had the brainwave to make a spoof of a movie that had just come out. It was a risky move. Nobody had any sense that Star Wars would become the worldwide cultural phenomenon that it did. And just as George Lucas’s space opera earned staggering amounts of money, so did Fosselius’s parody, Hardware Wars. You can watch it above. Made for a mere eight grand, the 13-minute movie became a pre-internet viral hit and a staple on the festival circuit, ultimately earning over $1,000,000 – an unheard of haul for a short film. In fact, in terms of money spent versus money earned, Hardware Wars ended up being far more profitable than Star Wars. And it’s considered the most profitable short film ever made.

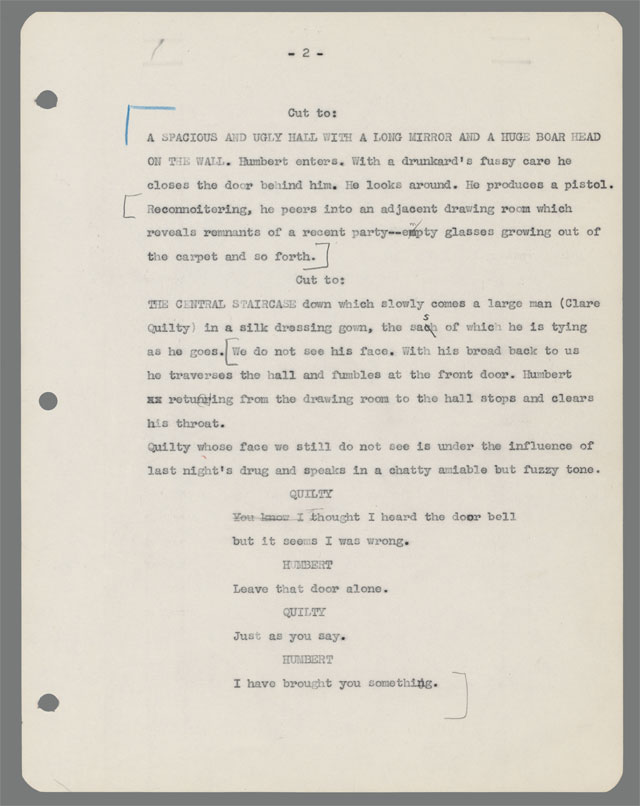

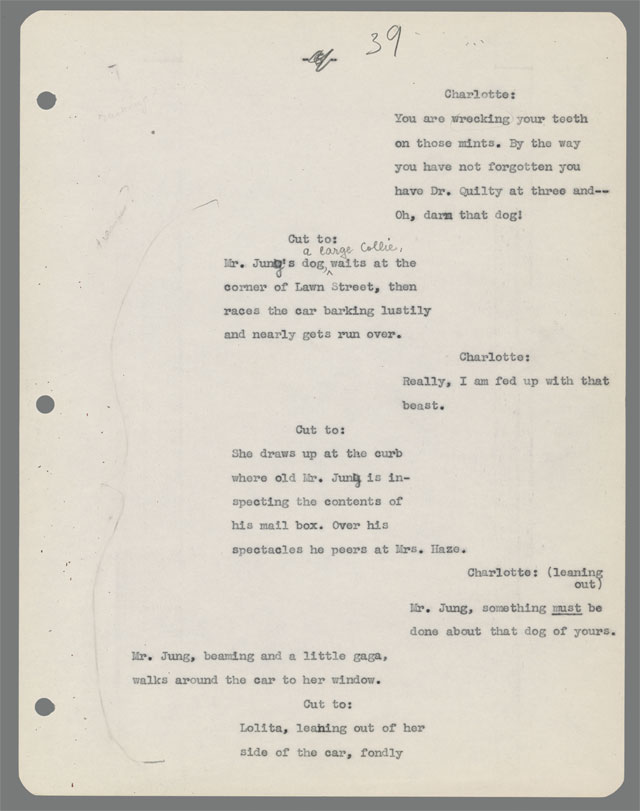

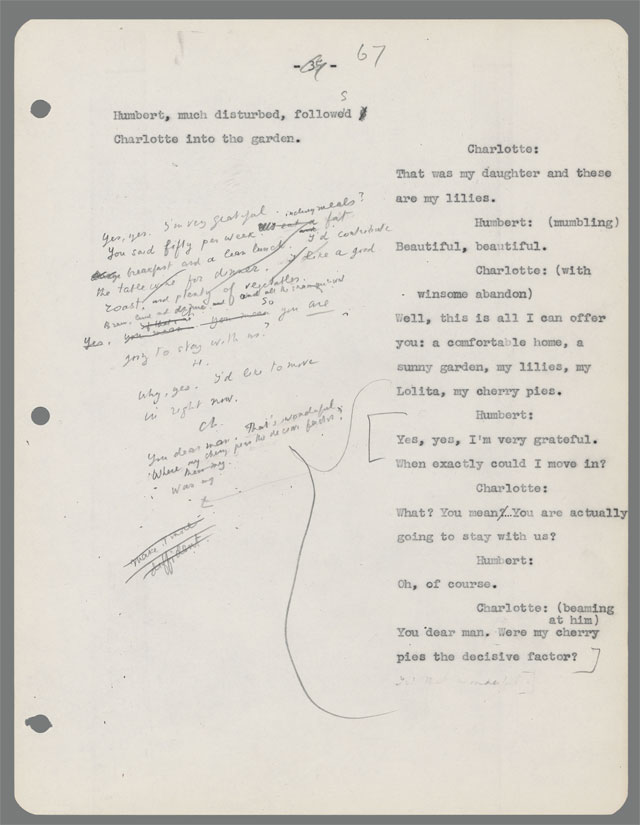

“I think a lot of the charm of that movie is the fact that we didn’t really know what we were doing,” said Scott Mathews, who donned a blonde wig to play the movie’s lead, Fluke Starbucker. The movie’s production is so gleefully cheap and half-assed that you can’t help but be charmed by it. Irons, toasters, and tape players are used in place of spaceships.

A canister vacuum cleaner stands in for R2D2, and Chewbacca appears to be a Cookie Monster puppet dyed brown. At one point, while on a desert planet of Tatooine, you see a beach-goer sauntering in the background. And Star Wars’s famous cantina scene is in this movie simply a stroll through a crowded tavern. If you know anything about the bar scene in 1970s San Francisco, you know that it was at least as weird as anything George Lucas managed to put up on the screen.

The often litigious Lucas reportedly really liked the movie, called it “cute.” He even invited Fosselius to voice the inconsolable sobs of Jabba the Hutt’s animal trainer after his beloved Rancor gets killed by Luke Skywalker in Return of the Jedi.

Hardware Wars ended up launching an entire subgenre of movie – the Star Wars fan film. And with the advent of Youtube and digital filmmaking technology, the ability of nerds and mavens to make increasingly sophisticated takes on Lucas’s universe became easier and easier. One of the better, and older, ones is Troops. A mash up of Star Wars and the reality TV series Cops, the short shows the challenges and the struggles of being an Imperial Stormtrooper. Check it out below.

via FilmmakerIQ

Related Content:

How Star Wars Borrowed From Akira Kurosawa’s Great Samurai Films

Freiheit, George Lucas’ Short Student Film About a Fatal Run from Communism (1966)

Watch the Very First Trailers for Star Wars, The Empire Strikes Back & Return of the Jedi (1976–83)

Joseph Campbell and Bill Moyers Break Down Star Wars as an Epic, Universal Myth

Hundreds of Fans Collectively Remade Star Wars; Now They Remake The Empire Strikes Back

4,000+ Free Movies Online: Great Classics, Indies, Noir, Westerns, Documentaries & MoreJonathan Crow is a Los Angeles-based writer and filmmaker whose work has appeared in Yahoo!, The Hollywood Reporter, and other publications. You can follow him at @jonccrow.