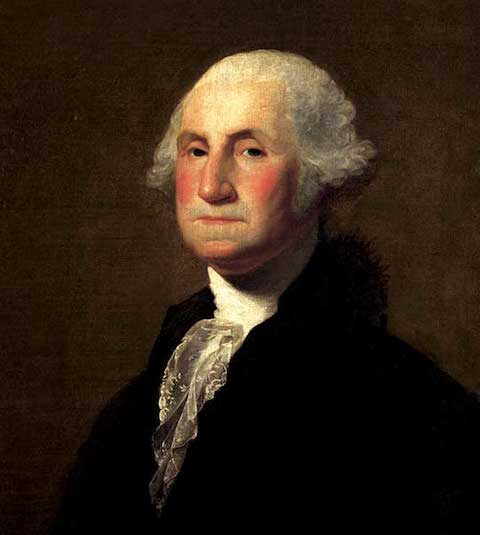

1. Every action done in company ought to be with some sign of respect to those that are present.

2. When in company, put not your hands to any part of the body not usually discovered.

3. Show nothing to your friend that may affright him.

4. In the presence of others, sing not to yourself with a humming voice, or drum with your fingers or feet.

5. If you cough, sneeze, sigh or yawn, do it not loud but privately, and speak not in your yawning, but put your handkerchief or hand before your face and turn aside.

6. Sleep not when others speak, sit not when others stand, speak not when you should hold your peace, walk not on when others stop.

7. Put not off your clothes in the presence of others, nor go out of your chamber half dressed.

8. At play and attire, it’s good manners to give place to the last comer, and affect not to speak louder than ordinary.

9. Spit not into the fire, nor stoop low before it; neither put your hands into the flames to warm them, nor set your feet upon the fire, especially if there be meat before it.

10. When you sit down, keep your feet firm and even, without putting one on the other or crossing them.

11. Shift not yourself in the sight of others, nor gnaw your nails.

12. Shake not the head, feet, or legs; roll not the eyes; lift not one eyebrow higher than the other, wry not the mouth, and bedew no man’s face with your spittle by approaching too near him when you speak.

13. Kill no vermin, or fleas, lice, ticks, etc. in the sight of others; if you see any filth or thick spittle put your foot dexterously upon it; if it be upon the clothes of your companions, put it off privately, and if it be upon your own clothes, return thanks to him who puts it off.

14. Turn not your back to others, especially in speaking; jog not the table or desk on which another reads or writes; lean not upon anyone.

15. Keep your nails clean and short, also your hands and teeth clean, yet without showing any great concern for them.

16. Do not puff up the cheeks, loll not out the tongue with the hands or beard, thrust out the lips or bite them, or keep the lips too open or too close.

17. Be no flatterer, neither play with any that delight not to be played withal.

18. Read no letter, books, or papers in company, but when there is a necessity for the doing of it, you must ask leave; come not near the books or writtings of another so as to read them unless desired, or give your opinion of them unasked. Also look not nigh when another is writing a letter.

19. Let your countenance be pleasant but in serious matters somewhat grave.

20. The gestures of the body must be suited to the discourse you are upon.

21. Reproach none for the infirmities of nature, nor delight to put them that have in mind of thereof.

22. Show not yourself glad at the misfortune of another though he were your enemy.

23. When you see a crime punished, you may be inwardly pleased; but always show pity to the suffering offender.

24. Do not laugh too loud or too much at any public spectacle.

25. Superfluous compliments and all affectation of ceremonies are to be avoided, yet where due they are not to be neglected.

26. In putting off your hat to persons of distinction, as noblemen, justices, churchmen, etc., make a reverence, bowing more or less according to the custom of the better bred, and quality of the persons. Among your equals expect not always that they should begin with you first, but to pull off the hat when there is no need is affectation. In the manner of saluting and resaluting in words, keep to the most usual custom.

27. ‘Tis ill manners to bid one more eminent than yourself be covered, as well as not to do it to whom it is due. Likewise he that makes too much haste to put on his hat does not well, yet he ought to put it on at the first, or at most the second time of being asked. Now what is herein spoken, of qualification in behavior in saluting, ought also to be observed in taking of place and sitting down, for ceremonies without bounds are troublesome.

28. If any one come to speak to you while you are are sitting stand up, though he be your inferior, and when you present seats, let it be to everyone according to his degree.

29. When you meet with one of greater quality than yourself, stop and retire, especially if it be at a door or any straight place, to give way for him to pass.

30. In walking, the highest place in most countries seems to be on the right hand; therefore, place yourself on the left of him whom you desire to honor. But if three walk together the middest place is the most honorable; the wall is usally given to the most worthy if two walk together.

31. If anyone far surpasses others, either in age, estate, or merit, yet would give place to a meaner than himself in his own lodging or elsewhere, the one ought not to except it. So he on the other part should not use much earnestness nor offer it above once or twice.

32. To one that is your equal, or not much inferior, you are to give the chief place in your lodging, and he to whom it is offered ought at the first to refuse it, but at the second to accept though not without acknowledging his own unworthiness.

33. They that are in dignity or in office have in all places precedency, but whilst they are young, they ought to respect those that are their equals in birth or other qualities, though they have no public charge.

34. It is good manners to prefer them to whom we speak before ourselves, especially if they be above us, with whom in no sort we ought to begin.

35. Let your discourse with men of business be short and comprehensive.

36. Artificers and persons of low degree ought not to use many ceremonies to lords or others of high degree, but respect and highly honor then, and those of high degree ought to treat them with affability and courtesy, without arrogance.

37. In speaking to men of quality do not lean nor look them full in the face, nor approach too near them at left. Keep a full pace from them.

38. In visiting the sick, do not presently play the physician if you be not knowing therein.

39. In writing or speaking, give to every person his due title according to his degree and the custom of the place.

40. Strive not with your superior in argument, but always submit your judgment to others with modesty.

41. Undertake not to teach your equal in the art himself professes; it savors of arrogancy.

42. Let your ceremonies in courtesy be proper to the dignity of his place with whom you converse, for it is absurd to act the same with a clown and a prince.

43. Do not express joy before one sick in pain, for that contrary passion will aggravate his misery.

44. When a man does all he can, though it succeed not well, blame not him that did it.

45. Being to advise or reprehend any one, consider whether it ought to be in public or in private, and presently or at some other time; in what terms to do it; and in reproving show no signs of cholor but do it with all sweetness and mildness.

46. Take all admonitions thankfully in what time or place soever given, but afterwards not being culpable take a time and place convenient to let him know it that gave them.

47. Mock not nor jest at any thing of importance. Break no jests that are sharp, biting, and if you deliver any thing witty and pleasant, abstain from laughing thereat yourself.

48. Wherein you reprove another be unblameable yourself, for example is more prevalent than precepts.

49. Use no reproachful language against any one; neither curse nor revile.

50. Be not hasty to believe flying reports to the disparagement of any.

51. Wear not your clothes foul, or ripped, or dusty, but see they be brushed once every day at least and take heed that you approach not to any uncleaness.

52. In your apparel be modest and endeavor to accommodate nature, rather than to procure admiration; keep to the fashion of your equals, such as are civil and orderly with respect to time and places.

53. Run not in the streets, neither go too slowly, nor with mouth open; go not shaking of arms, nor upon the toes, kick not the earth with your feet, go not upon the toes, nor in a dancing fashion.

54. Play not the peacock, looking every where about you, to see if you be well decked, if your shoes fit well, if your stockings sit neatly and clothes handsomely.

55. Eat not in the streets, nor in the house, out of season.

56. Associate yourself with men of good quality if you esteem your own reputation; for ’tis better to be alone than in bad company.

57. In walking up and down in a house, only with one in company if he be greater than yourself, at the first give him the right hand and stop not till he does and be not the first that turns, and when you do turn let it be with your face towards him; if he be a man of great quality walk not with him cheek by jowl but somewhat behind him, but yet in such a manner that he may easily speak to you.

58. Let your conversation be without malice or envy, for ’tis a sign of a tractable and commendable nature, and in all causes of passion permit reason to govern.

59. Never express anything unbecoming, nor act against the rules moral before your inferiors.

60. Be not immodest in urging your friends to discover a secret.

61. Utter not base and frivolous things among grave and learned men, nor very difficult questions or subjects among the ignorant, or things hard to be believed; stuff not your discourse with sentences among your betters nor equals.

62. Speak not of doleful things in a time of mirth or at the table; speak not of melancholy things as death and wounds, and if others mention them, change if you can the discourse. Tell not your dreams, but to your intimate friend.

63. A man ought not to value himself of his achievements or rare qualities of wit; much less of his riches, virtue or kindred.

64. Break not a jest where none take pleasure in mirth; laugh not aloud, nor at all without occasion; deride no man’s misfortune though there seem to be some cause.

65. Speak not injurious words neither in jest nor earnest; scoff at none although they give occasion.

66. Be not froward but friendly and courteous, the first to salute, hear and answer; and be not pensive when it’s a time to converse.

67. Detract not from others, neither be excessive in commanding.

68. Go not thither, where you know not whether you shall be welcome or not; give not advice without being asked, and when desired do it briefly.

69. If two contend together take not the part of either unconstrained, and be not obstinate in your own opinion. In things indifferent be of the major side.

70. Reprehend not the imperfections of others, for that belongs to parents, masters and superiors.

71. Gaze not on the marks or blemishes of others and ask not how they came. What you may speak in secret to your friend, deliver not before others.

72. Speak not in an unknown tongue in company but in your own language and that as those of quality do and not as the vulgar. Sublime matters treat seriously.

73. Think before you speak, pronounce not imperfectly, nor bring out your words too hastily, but orderly and distinctly.

74. When another speaks, be attentive yourself and disturb not the audience. If any hesitate in his words, help him not nor prompt him without desired. Interrupt him not, nor answer him till his speech be ended.

75. In the midst of discourse ask not of what one treats, but if you perceive any stop because of your coming, you may well entreat him gently to proceed. If a person of quality comes in while you’re conversing, it’s handsome to repeat what was said before.

76. While you are talking, point not with your finger at him of whom you discourse, nor approach too near him to whom you talk, especially to his face.

77. Treat with men at fit times about business and whisper not in the company of others.

78. Make no comparisons and if any of the company be commended for any brave act of virtue, commend not another for the same.

79. Be not apt to relate news if you know not the truth thereof. In discoursing of things you have heard, name not your author. Always a secret discover not.

80. Be not tedious in discourse or in reading unless you find the company pleased therewith.

81. Be not curious to know the affairs of others, neither approach those that speak in private.

82. Undertake not what you cannot perform but be careful to keep your promise.

83. When you deliver a matter do it without passion and with discretion, however mean the person be you do it to.

84. When your superiors talk to anybody hearken not, neither speak nor laugh.

85. In company of those of higher quality than yourself, speak not ’til you are asked a question, then stand upright, put off your hat and answer in few words.

86. In disputes, be not so desirous to overcome as not to give liberty to each one to deliver his opinion and submit to the judgment of the major part, especially if they are judges of the dispute.

87. Let your carriage be such as becomes a man grave, settled and attentive to that which is spoken. Contradict not at every turn what others say.

88. Be not tedious in discourse, make not many digressions, nor repeat often the same manner of discourse.

89. Speak not evil of the absent, for it is unjust.

90. Being set at meat scratch not, neither spit, cough or blow your nose except there’s a necessity for it.

91. Make no show of taking great delight in your victuals. Feed not with greediness. Eat your bread with a knife. Lean not on the table, neither find fault with what you eat.

92. Take no salt or cut bread with your knife greasy.

93. Entertaining anyone at table it is decent to present him with meat. Undertake not to help others undesired by the master.

94. If you soak bread in the sauce, let it be no more than what you put in your mouth at a time, and blow not your broth at table but stay ’til it cools of itself.

95. Put not your meat to your mouth with your knife in your hand; neither spit forth the stones of any fruit pie upon a dish nor cast anything under the table.

96. It’s unbecoming to heap much to one’s mea. Keep your fingers clean and when foul wipe them on a corner of your table napkin.

97. Put not another bite into your mouth ’til the former be swallowed. Let not your morsels be too big for the jowls.

98. Drink not nor talk with your mouth full; neither gaze about you while you are drinking.

99. Drink not too leisurely nor yet too hastily. Before and after drinking wipe your lips. Breathe not then or ever with too great a noise, for it is uncivil.

100. Cleanse not your teeth with the tablecloth, napkin, fork or knife, but if others do it, let it be done with a pick tooth.

101. Rinse not your mouth in the presence of others.

102. It is out of use to call upon the company often to eat. Nor need you drink to others every time you drink.

103. In company of your betters be not longer in eating than they are. Lay not your arm but only your hand upon the table.

104. It belongs to the chiefest in company to unfold his napkin and fall to meat first. But he ought then to begin in time and to dispatch with dexterity that the slowest may have time allowed him.

105. Be not angry at table whatever happens and if you have reason to be so, show it not but on a cheerful countenance especially if there be strangers, for good humor makes one dish of meat a feast.

106. Set not yourself at the upper of the table but if it be your due, or that the master of the house will have it so. Contend not, lest you should trouble the company.

107. If others talk at table be attentive, but talk not with meat in your mouth.

108. When you speak of God or His attributes, let it be seriously and with reverence. Honor and obey your natural parents although they be poor.

109. Let your recreations be manful not sinful.

110. Labor to keep alive in your breast that little spark of celestial fire called conscience.

In early January, we brought you a set of

In early January, we brought you a set of