Journalism Under Siege: A Free Online Course from Stanford Explores the Imperiled Freedom of the Press

This past fall, Stanford Continuing Studies and the John S. Knight Journalism Fellowships teamed up to offer an important course on the challenges facing journalism and the freedom of the press. Called Journalism Under Siege? Truth and Trust in a Time of Turmoil, the five-week course featured 28 journalists and media experts, all offering insights on the emerging challenges facing the media across the United States and the wider world. The lectures/presentations are now all online. Find them below, along with the list of guest speakers, which includes Alex Stamos who blew the whistle on Russia’s manipulation of the Facebook platform during the 2016 election. Journalism Under Siege will be added to our collection, 1,700 Free Online Courses from Top Universities.

Weekly Sessions:

- Week 1 – First Draft of History: How a Free Press Protects Freedom; Part One, Part Two

- Week 2 – Power to the People: Holding the Powerful Accountable; Part One, Part Two

- Week 3 – Picking Sides? How Journalists Cover Bias, Intolerance and Injustice; Part One, Part Two

- Week 4 – The Last Stand of Local News; Part One, Part Two

- Week 5 – The Misinformation Society; Part One, Part Two

Guest Speakers:

- Hannah Allam, national reporter, BuzzFeed News

- Roman Anin, investigations editor, Novaya Gazeta, Moscow

- Hugo Balta, president, National Association of Hispanic Journalists

- Sally Buzbee, executive editor, Associated Press (AP)

- Neil Chase, executive editor, San Jose Mercury News

- Audrey Cooper, editor-in-chief, San Francisco Chronicle

- Jenée Desmond-Harris, staff editor, NYT Opinion, New York Times

- Jiquanda Johnson, founder and publisher, Flint Beat

- Joel Konopo, managing partner, INK Centre for Investigative Journalism, Gaborone, Botswana

- Richard Lui, anchor, MSNBC and NBC News

- Geraldine Moriba, former vice president for diversity and inclusion, CNN

- Bryan Pollard, president, Native American Journalists Association

- Cecile Prieur, deputy editor, Le Monde, Paris

- Joel Simon, executive director, Committee to Protect Journalists

- Alex Stamos, former Facebook chief security officer

- Marina Walker Guevara, winner of the 2017 Pulitzer Prize for Explanatory Reporting for coordinating the Panama Papers investigation

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Read More...Isaac Asimov Predicts the Future of Civilization–and Recommends Ways to Ensure That It Survives (1978)

When we talk about what could put an end to civilization today, we usually talk about climate change. The frightening scientific research behind that phenomenon has, apart from providing a seemingly infinite source of fuel for the blaze of countless political debates, also inspired a variety of dystopian visions, credible and otherwise, of no small number of science-fiction writers. One wonders what a science-fictional mind of, say, Isaac Asimov’s caliber would make of it. Asimov died in 1992, a few years before climate change attained the presence in the zeitgeist it has today, but we can still get a sense of his approach to thinking about these kinds of literally existential questions from his 1978 talk above.

When people talked about what could put an end to civilization in 1978, they talked about overpopulation. A decade earlier, Stanford biologist Paul Ehrlich published The Population Bomb, whose early editions opened with these words: “The battle to feed all of humanity is over. In the 1970s hundreds of millions of people will starve to death in spite of any crash programs embarked upon now. At this late date nothing can prevent a substantial increase in the world death rate.” With these and other grim pronouncements lodged in their minds, the bestselling book’s many readers saw humanity faced with a stark choice: let that death rate increase, or proactively lower the birth rate.

A decade later, Asimov frames the situation in the same basic terms, though he shows more optimism — or at least inventiveness — in addressing it, supported by the workings of his powerful imagination. This isn’t to say that the images he throws out are exactly utopian: he sees humanity, growing at then-current rates, ultimately housed in “one world-girdling skyscraper, partially apartment houses, partially factories, partially all kinds of things — schools, colleges — and the entire ocean taken out of its bed and placed on the roof, and growing algae or something like that. Because all those people will have to be fed, and the only way they can be fed is to allow no waste whatever.”

This necessity will be the mother of such inventions as “thick conduits leading down into the ocean water from which you take out the algae and all the other plankton, or whatever the heck it is, and you pound it and you separate it and you flavor it and you cook it, and finally you have your pseudo-steak and your mock veal and your healthful sub-vegetables and so on.” Where to get the nutrients to fertilize the growth of more algae? “Only from chopped-up corpses and human wastes.” It would probably interest Asimov, and certainly amuse him, to see how much research into algae-based food goes on here in the 21st century (let alone the popularity of an algae-utilizing meal replacement beverage called Soylent). But however delicious all those become, humanity will need more to live: energy, space, and yes, a comfortable ambient temperature.

Asimov’s suite of proposed solutions, the explanation of which he spins into high and often prescient entertainment, includes birth control, solar power, lunar mining, and the repurposing of some of the immense budget spent on “war machines.” The volume of applause in the room shows how heartily some agreed with him then, and perspectives like Asimov’s have drawn more adherents in the more than 40 years since, about a decade after Asimov confidently predicted that the world would run out of oil, a time when an increasing number of developed countries have begun to worry about their falling birthrates. But then, Asimov also imagined that Mount Everest was unconquerable because Martians lived on top of it in a story published a seven months after Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay made it up there — a fact he made a rule of cheerfully admitting whenever he started with the predictions.

Related Content:

Isaac Asimov’s Favorite Story “The Last Question” Read by Isaac Asimov— and by Leonard Nimoy

Isaac Asimov Explains His Three Laws of Robots

Free: Isaac Asimov’s Epic Foundation Trilogy Dramatized in Classic Audio

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

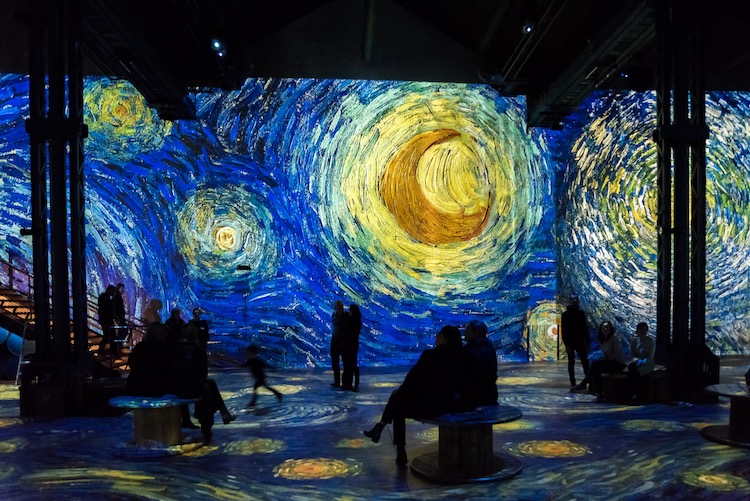

Read More...Take a Journey Inside Vincent Van Gogh’s Paintings with a New Digital Exhibition

Vincent van Gogh died in 1890, long before the emergence of any of the visual technologies that impress us here in the 21st century. But the distinctive vision of reality expressed through paintings still captivates us, and perhaps captivates us more than ever: the latest of the many tributes we continue to pay to van Gogh’s art takes the form Van Gogh, Starry Night, a “digital exhibition” at the Atelier des Lumières, a disused foundry turned projector- and sound system-laden multimedia space in Paris. “Projected on all the surfaces of the Atelier,” its site says of the exhibition, “this new visual and musical production retraces the intense life of the artist.”

Van Gogh’s intensity manifested in various ways, including more than 2,000 paintings painted in the last decade of his life alone. Van Gogh, Starry Night surrounds its visitors with the painter’s work, “which radically evolved over the years, from The Potato Eaters (1885), Sunflowers (1888) and Starry Night (1889) to Bedroom at Arles (1889), from his sunny landscapes and nightscapes to his portraits and still lives.”

It also takes them through the journey of his life itself, including his “sojourns in Neunen, Arles, Paris, Saint-Rémy-de-Provence, and Auvers-sur-Oise.” It will also take them to Japan, a land van Gogh dreamed of and that inspired him to create “the art of the future,” with a supplemental show titled Dreamed Japan: Images of the Floating World.

Both Van Gogh, Starry Night and Dreamed Japan run until the end of this year. If you happen to have a chance to make it out to the Atelier des Lumières, first consider downloading the exhibition’s smartphone and tablet application that provides recorded commentary on van Gogh’s masterpieces. That counts as one more layer of this elaborate audiovisual experience that, despite employing the height of modern museum technology, nevertheless draws all its aesthetic inspiration from 19th-century paintings — and will send those who experience it back to those 19th-century paintings with a heightened appreciation. Nearly 130 years after Van Gogh’s death, we’re still using all the ingenuity we can muster to see the world as he did.

Related Content:

13 Van Gogh’s Paintings Painstakingly Brought to Life with 3D Animation & Visual Mapping

Van Gogh’s 1888 Painting, “The Night Cafe,” Animated with Oculus Virtual Reality Software

Download Hundreds of Van Gogh Paintings, Sketches & Letters in High Resolution

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

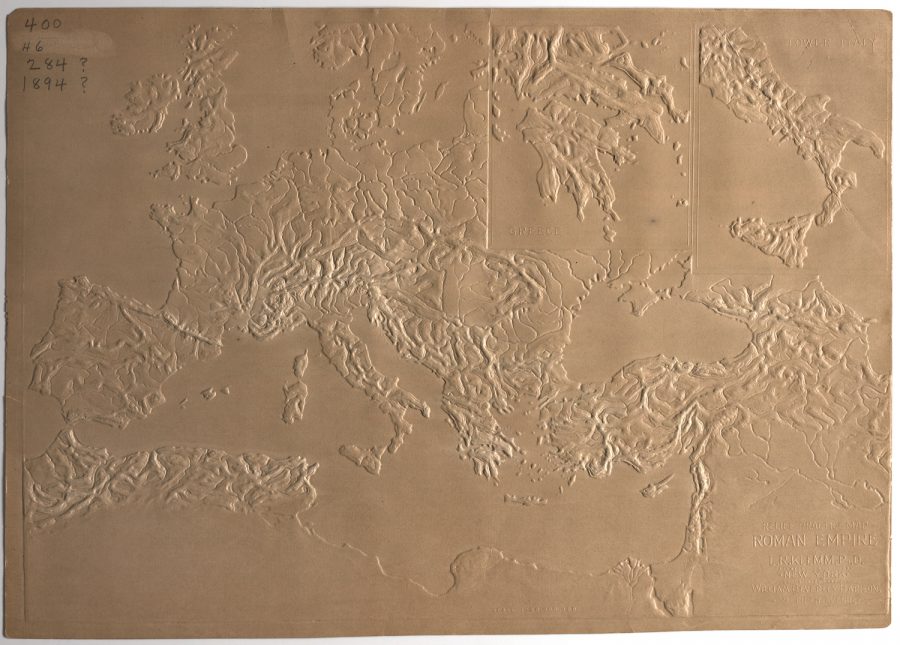

Read More...A Tactile Map of the Roman Empire: An Innovative Map That Allowed Blind & Sighted Students to Experience Geography by Touch (1888)

From curb cuts to safer playgrounds, the public spaces we occupy have been transformed for the better as they become easier for different kinds of bodies to navigate. Closed captioning and printable transcripts benefit millions, whatever their level of ability. Accessibility tools on the web improve everyone’s experience and provide the impetus for technologies that engage more of our senses. While smell may not be a high priority for developers, attention to a sense most sighted people tend to take for granted could open up an age of using feedback systems to make visual media touch responsive.

One such tactile system designed for Smithsonian Museums has developed “new methods for fabricating replicas of museum artifacts and other 3D objects that describe themselves when touched,” reported the National Rehabilitation Information Center in a February post for Low Vision Awareness Month. “Depth effects are achieved by varying the height of relief of raised lines, and texture fills help improve awareness of figure-ground distinctions.” Haptic feedback technology, like that the iPhone and various video game systems have introduced over the past few years, promises to open up much more of the world to the visually-impaired… and to everyone else.

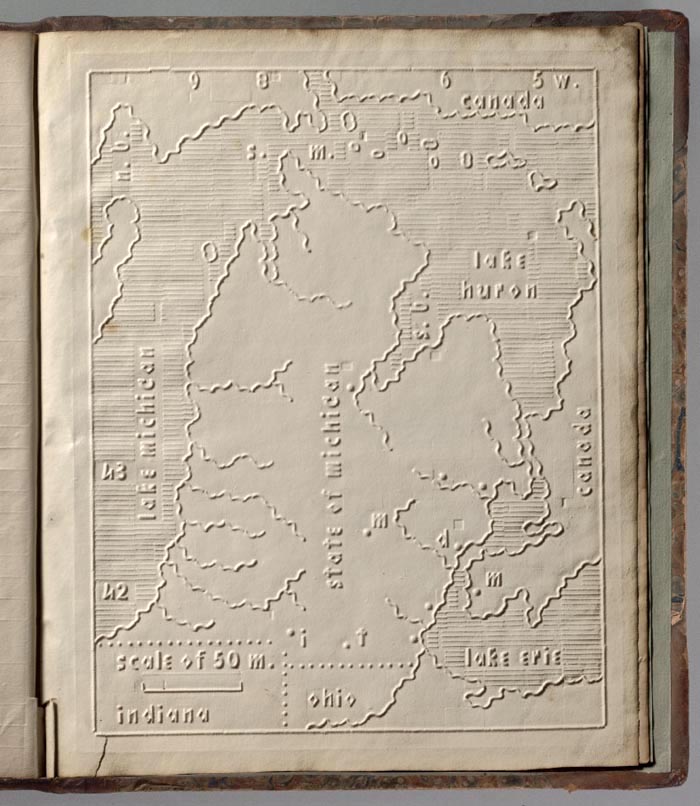

One invention introduced over a century ago held out the same promise. The tactile map, “an innovation of the 19th century,” writes Rebecca Onion at Slate, “allowed both blind and sighted students to feel their way across a given geography.” One popularizer of the tactile map, former school superintendent L.R. Klemm, who made the example above, believed that “while the waterproof map could be used to teach students without sight,” it could also “fruitfully engage sighted students through the sense of touch.”

Though created in Europe, tactile maps have had a relatively long history in the U.S., debuting in 1837 with an atlas of the United States developed by Samuel Gridley Howe of the Perkins School for the Blind. (See Michigan above.) Klemm’s map up top, depicting the Roman Empire (284–476 CE), is a later entry, patented in 1888, and, he promises it’s a decided improvement on earlier models. In an article that year for The American Teacher, he described “the painstaking process of creating one of these relief maps,” notes Onion, “a process he used as another teaching tool, enlisting students to help him scrape and carve plaster casts into negative shapes of mountain ranges and plateaus.”

Those students, he wrote, developed “so clear a conception of the topography and irrigation of the respective country that it can scarcely be improved.” Tactile accuracy meant a lot to Klemm. In text published alongside the map, he took Howe and other publishers to task for raising water above land, an idea “so unnatural, that the mind never thoroughly becomes accustomed to it.” Klemm also critiques a French map of “very perfect construction.” This handmade version, he says, though ingenious, is “expensive and very inefficient.” While its utility “in the case of institutions, and for the use of pupils of the wealthy classes is undoubted… the costliness of maps constructed on such a principle places the advantages of the system beyond the reach of the blind generally.”

Klemm’s concern for the quality, accuracy, utility, and economic accessibility of this early accessibility tool is admirable. And though you can’t experience it through your screen, his method is probably a vastly-improved way of learning geography for many people, sighted or not. Tactile maps did not quite become general use technologies, but their digital progeny may soon have us all experiencing more of the world through touch. View and download a larger (2D) version of Klemm’s map and learn more at 19th Century Disability Cultures & Contexts.

via Slate

Related Content:

Vintage Geological Maps Get Turned Into 3D Topographical Wonders

A Radical Map Puts the Oceans–Not Land–at the Center of Planet Earth (1942)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hear a Six-Hour Mix Tape of Hunter S. Thompson’s Favorite Music & the Songs Name-Checked in His Gonzo Journalism

Of all the musical moments in Hunter S. Thompson’s formidable corpus of “gonzo journalism,” which one comes most readily to mind? I would elect the scene in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas when Thompson’s alter-ego Raoul Duke finds his attorney “Dr. Gonzo” in the bathtub, “submerged in green water — the oily product of some Japanese bath salts he’d picked up in the hotel gift shop, along with a new AM/FM radio plugged into the electric razor socket. Top volume. Some gibberish by a thing called ‘Three Dog Night,’ about a frog named Jeremiah who wanted ‘Joy to the World.’ First Lennon, now this, I thought. Next we’ll have Glenn Campbell screaming ‘Where Have All the Flowers Gone?’ ”

But Dr. Gonzo, his state even more altered than usual, really wants to hear only one song: Jefferson Airplane’s “White Rabbit.” He wants “a rising sound,” and what’s more, he demands that “when it comes to that fantastic note where the rabbit bites its own head off,” Duke throw the radio in the tub with him.

Duke refuses, explaining that “it would blast you right through the wall — stone-dead in ten seconds.” Yet Dr. Gonzo, who insists he just wants to get “higher,” will have none of it, forcing Duke to engage in trickery that takes to a new depth the book’s already-deep level of craziness. Such, at the time, was the power of not just drugs but of the even more mind-altering product known as music.

Nothing evokes a period of recent history more vividly than its songs, especially in the case of the 1960s and early 1970s that Thompson’s prose captured with such improbable eloquence. Now, thanks to London’s NTS Radio (they of the spiritual jazz and Haruki Murakami mixes), you can spend a good six hours in that Thompsonian period whenever you like by streaming their Hunter S. Thompson Day, consisting of two three-hour mixes composed by Edu Villarroel, creator of the Spotify playlist “Gonzo Tapes: Too Weird To Live, Too Rare To Die!” Both that playlist and these mixes feature many of the 60s names you might expect: not just Jefferson Airplane but Buffalo Springfield, Jimi Hendrix, the Rolling Stones, Bob Dylan, Cream, Captain Beefheart, and many more besides.

Those artists appear on one particularly important source for these mixes, Thompson’s list of the ten best albums of the 60s. But Hunter S. Thompson Day also offers deeper cuts of Thompsoniana as well, including pieces of Terry Gilliam’s 1998 film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas as well as clips from other media in which the real Thompson appeared, in fully gonzo character as always. Villarroel describes these mixes as “best served with a couple tabs of sunshine acid, tall glass of Wild Turkey with ice and Mezcal on the side,” but you may well derive a similar experience from listening while partaking of another powerful substance: Thompson’s writing, still so often imitated without ever replicating its effect, which you can get started reading here on Open Culture.

Related Content:

Hear the 10 Best Albums of the 1960s as Selected by Hunter S. Thompson

Hunter S. Thompson Remembers Jimmy Carter’s Captivating Bob Dylan Speech (1974)

Hunter S. Thompson Interviews Keith Richards, and Very Little Makes Sense

Read 11 Free Articles by Hunter S. Thompson That Span His Gonzo Journalist Career (1965–2005)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Watch the Last Time Peter Tork (RIP) & The Monkees Played Together During Their 1960s Heyday: It’s a Psychedelic Freakout

Peter Tork died yesterday at age 77. You might not have heard the news over the deafening alarms in your social media feeds lately. But a muted response is also noteworthy because of the way Tork’s fame imploded at the end of the sixties, at a time when he might have become the kind of rock star he and his fellow Monkees had proved they could become, all on their own, without the help of any studio trickery, thanks very much. The irony of making this bold statement with a feature film was not lost on the band at all.

The film was Head, co-written and co-produced by Jack Nicholson, who appears alongside the Monkees, Teri Garr, Annette Funicello, Frank Zappa, Sonny Liston, Jerry Lee Lewis, Fats Domino, and Little Richard, among many other famous guest stars and musicians. Dennis Hopper and Toni Basil pop up, and the soundtrack, largely written and played by the band, is a truly groovy psych rock masterpiece and their last album to feature Tork until a reunion in the mid-80s.

Head was a weird, cynical, embittered, yet brilliant, attempt to torpedo everything the Monkees had been to their fans—teen pop idols and goofy Beatles rip-offs at a time when The Beatles had maybe gotten too edgy for some folks. And while it may have taken too much of a toll on the band, especially Tork, for them to recover, it’s clear that they had an absolute blast making both the movie and the record, even as their professional relationships collapsed.

Tork’s best songwriting contribution to Head, and maybe to the Monkees catalog on the whole, is “Can You Dig It,” a meditation on “it” that takes what might have been cheap hipster appropriation in a funky, pseudo-deep, vaguely Eastern direction free of guile—it’s light and breezy, like the Monkees, but also sinister and slinky, like Donovan or the folk rock of Brian Jones, and also spidery and jangly like Roger McGuinn. In the estimation of many a psychedelic rock fan, this is music that deserves a place beside its obvious influences. That Monkees fans could not dig it at the time only reflects poorly on them, but since some of them were fans of what they thought was a slapstick comedy troupe or a backup act for dreamy Davy Jones, they can hardly be blamed.

Cast as the Ringo of the gang (The Monkees and Head director Bob Rafelson compared him to Harpo Marx), Tork brought to it a similarly serious whimsy, and when he was finally allowed to show what he could do—both as a musician and a songwriter—he more than acquitted himself. Where Ringo mastered idiot savant one-liners, Tork excelled in the kind of oblique riffs that characterized his playing—he was the least talented vocalist in the band, but the most talented musician and the only one allowed to play on the band’s first two records. Tork played bass, guitar, keyboards, banjo, harpsichord, and other instruments fluently. He honed his craft, and his “lovable dummy” persona on Greenwich Village coffeehouse stages.

It’s not hard to argue that the Monkees rose above their TV origins to become bona fide pop stars with the songwriting and promotional instincts to match, but Head, both film and album, make them a band worth revisiting for all sorts of other reasons. Now a widely-admired cult classic, in 1968, the movie “surfaced briefly and then sank like a costumed dummy falling into a California canal,” writes Petra Mayer at NPR, in reference to Head’s first scene, in which Micky Dolenz appears to commit suicide. If the Monkees had been trying in earnest to do the same to their careers, they couldn’t have had more success. Head cost $750,000 and made back $16,000. “It was clear they were in free fall,” Andy Greene writes at Rolling Stone.

“After that debacle,” writes Greene, they could have tried a return to the original formula to recoup their losses, but instead “they decided to double down on psychedelic insanity” in an NBC television special, 33⅓ Revolutions per Monkee, greenlighted that year after the huge chart success of “Daydream Believer.” Tork had already announced that he was leaving the band as the cameras rolled on the very loosely plotted variety show. He stuck around till the end of filming, however, and played the last live performance with The Monkees for almost 20 years in the bang-up finale of “Listen to the Band” (top) which “quickly devolves into a wild psychedelic freakout crammed with guest stars.” Tork, behind the keys, first turns the downbeat Neil Young-like, Nesmith-penned tune into the rave-up it becomes. It’s a glorious send-off for a version of the Monkees people weren’t ready to hear in ’68.

Related Content:

Watch Frank Zappa Play Michael Nesmith on The Monkees (1967)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

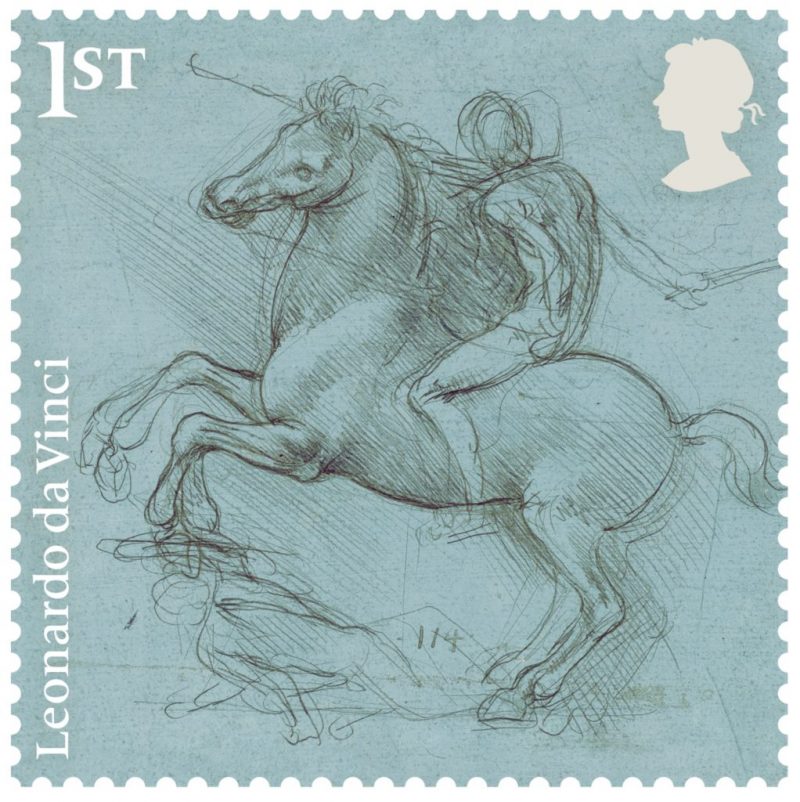

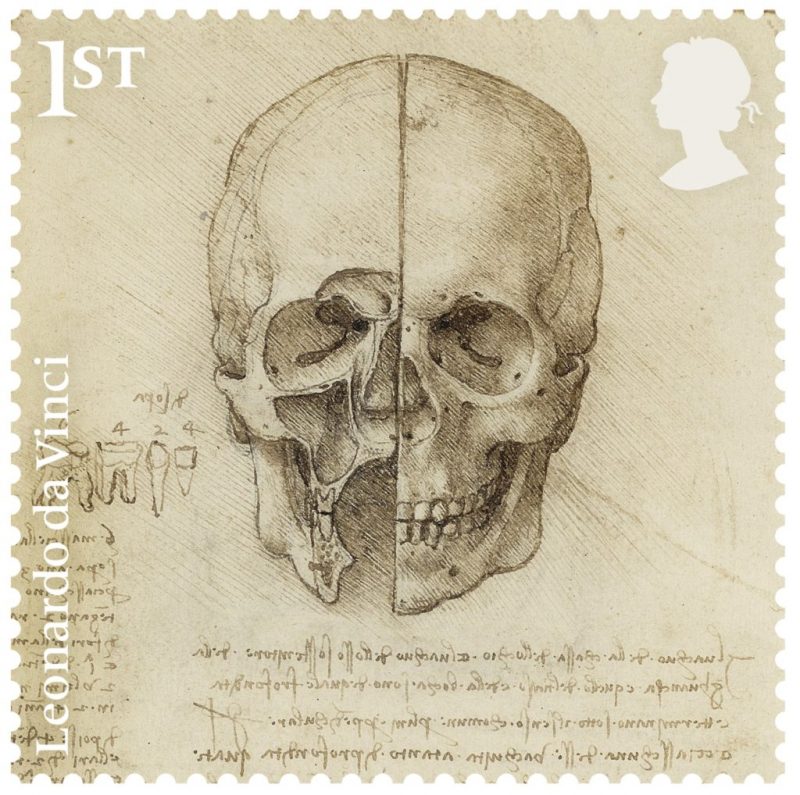

Read More...Famous Drawings by Leonardo da Vinci Celebrated in a New Series of Stamps

No special occasion is required to celebrate Leonardo da Vinci, but the fact that he died in 1519 makes this year a particularly suitable time to look back at his vast, innovative, and influential body of work. Just last month, “Leonardo da Vinci: A Life in Drawing” opened in twelve museums across the United Kingdom. “144 of Leonardo da Vinci’s greatest drawings in the Royal Collection are displayed in 12 simultaneous exhibitions across the UK,” says the exhibition’s site, with each venue’s drawings “selected to reflect the full range of Leonardo’s interests – painting, sculpture, architecture, music, anatomy, engineering, cartography, geology and botany.”

The Royal Collection Trust, writes Artnet’s Sarah Cascone, has even “sent a dozen drawings from Windsor Castle to each of the 12 participating institutions.” They’d previously been in Windsor Castle’s Print Room, the home of a collection of old master prints and drawings routinely described as one of the finest in the world.

Now displayed at institutions like Liverpool’s Walker Art Gallery, Sheffield’s Millennium Gallery, Belfast’s Ulster Museum, and Cardiff’s National Museum Wales, this selection of Leonardo’s drawings will be much more accessible to the public during the exhibition than before.

But the Royal Mail has made sure that the drawings will be even more widely seen, doing its part for the 500th anniversary of Leonardo’s death by issuing them in stamp form.

“The stamps depict several well-known works,” writes Artnet’s Kate Brown, “such as The skull sectioned (1489) and The head of Leda (1505–08), a study for his eventual painting of the myth of Leda, the queen of Sparta, which was the most valuable work in Leonardo’s estate when he died and was apparently destroyed around 1700. Other stamps show the artist’s studies of skeletons, joints, and cats.”

While none of these images enjoy quite the cultural profile of a Vitruvian Man, let alone a Mona Lisa, they all show that whatever Leonardo drew, he drew it in a way revealing that he saw it like no one else did (possibly due in part, as we’ve previously posted about here on Open Culture, to an eye disorder).

Though that may come across more clearly at the scale of the originals than at the scale of postage stamps, even a glimpse at the intellectually boundless Renaissance polymath’s drawings compressed into 21-by-24-millimeter squares will surely be enough to draw many into his still-inspirational artistic and scientific world. To the intrigued, may we suggest plunging into his 570 pages of notebooks?

Note: If you live in the San Francisco Bay Area, consider attending the new course–The Genius of Leonardo da Vinci: A 500th Anniversary Celebration–being offered through Stanford Continuing Studies. Registration opens on February 25. The class runs from April 16 through June 4.

Related Content:

Leonardo da Vinci’s Bizarre Caricatures & Monster Drawings

New Stamp Collection Celebrates Six Novels by Jane Austen

Postage Stamps from Bhutan That Double as Playable Vinyl Records

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Michel Foucault Offers a Clear, Compelling Introduction to His Philosophical Project (1966)

Theorist Michel Foucault first “rose to prominence,” notes Aeon, “as existentialism fell out of favor among French intellectuals.” His first major work, The Order of Things: An Archaeology of the Human Sciences, proposed a new methodology based on the “disappearance of Man” as a metaphysical category. The ahistorical assumptions that had plagued philosophy made us too comfortable, he thought, with historical systems that imprisoned us. “I would like to consider our own culture,” he says in the 1966 interview with Pierre Dumayet above, “to be something as foreign to us.”

The kind of estrangement Foucault induced in his ethnologies, genealogies, and histories of Western modernity opened a space for critiques of knowledge itself as a “foreign phenomenon,” he says. Madness and Civilization, The Birth of the Clinic, The Order of Things, and Discipline and Punish examine systems—the asylum, the medical profession, the sciences, and prisons—and allow us to see how ideologies are produced by instrumental uses of language and technology.

Foucault shifted his focus in the last period of his career, after a 1975 LSD trip and subsequent experiences in Berkeley changed his outlook. Yet he continued, in his monumental, unfinished, multi-volume History of Sexuality to demonstrate how modes of philosophical and scientific discourse gave rise to cultural phenomena we take for granted as natural states. Foucault was a critic of the way the psychiatry and medicine pathologized human behavior and created systems of exclusion and correction. In his final work, he examined the classical history of ethical discipline and self-improvement.

We might recognize the remnants of this history in our contemporary culture when he writes, in The History of Sexuality, Volume 3, that “improvement, the perfection of the soul that one seeks in philosophy…. Increasingly assumes a medical coloration.” Foucault described the ways in which pleasure and desire were highly circumscribed by utilitarian systems of control and self-control. It’s hard to say how much of this early interview the later Foucault would have endorsed, but it’s yet another example of how lucid and perceptive he was as a thinker, despite an undeserved reputation for difficulty and obscurity.

He admits, however, the inherent difficulty of his project: the self-reflective critique of a modern European intellectual, through the very categories of thought that make up the European intellectual tradition. But “after all,” he says, “how can we know ourselves if not with our own knowledge?” The endeavor requires a “complete twisting of our reason on itself.” Few thinkers have been able to make such moves with as much clarity and scholarly rigor as Foucault.

via Aeon

Related Content:

Hear Hours of Lectures by Michel Foucault: Recorded in English & French Between 1961 and 1983

Michel Foucault: Free Lectures on Truth, Discourse & The Self (UC Berkeley, 1980–1983)

An Animated Introduction to Michel Foucault, “Philosopher of Power”

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

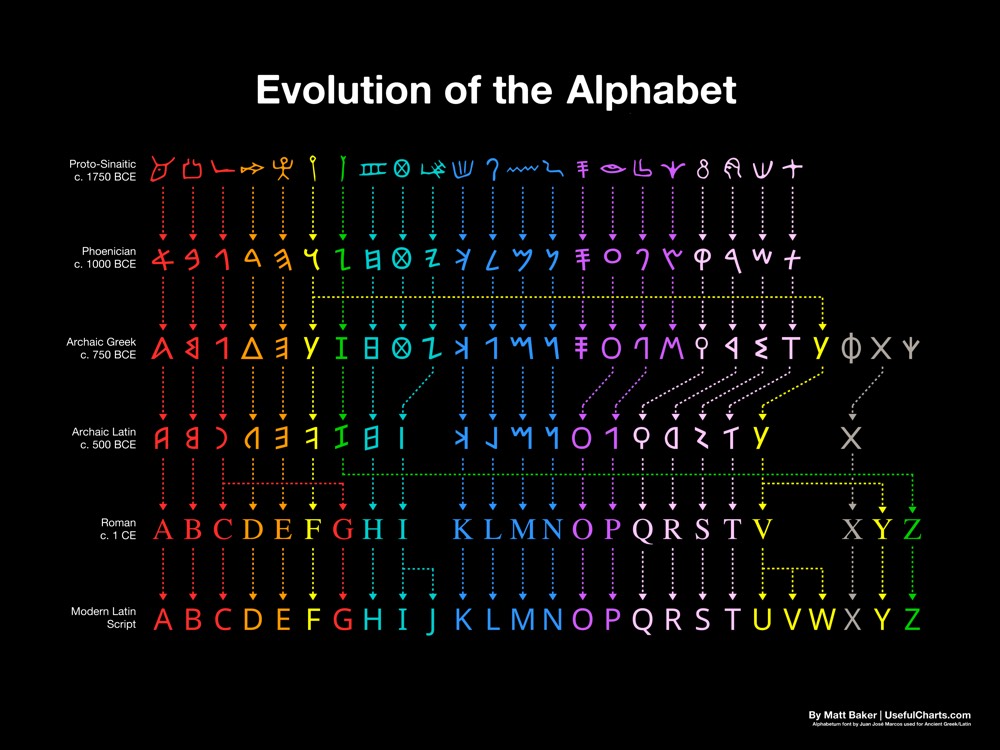

Read More...The Evolution of the Alphabet: A Colorful Flowchart, Covering 3,800 Years, Takes You From Ancient Egypt to Today

No matter our native language, we all have to learn a writing system. And whichever language we learn, its writing system had to come from somewhere. Take English, the language you’re reading right now and one written in Latin script, which it shares with a range of other tongues: the European likes of French, Spanish, and German, of course, but now also Icelandic, Swahili, Tagalog, and a great many more besides. The video above by Matt Baker of UsefulCharts explains just where this increasingly widespread writing system came from, tracing its origins all the way back to the Proto-Sinaitic script of Egypt in 1750 BCE.

As revealed in the video, or by the poster available for purchase from UsefulCharts, the letters used to write English today evolved from there “through Phoenician, early Greek and early Latin, to their present forms. You can see how some letters were dropped and others ended up evolving into more than one letter.”

The color-coding and direction dotted lines help to make clearly legible what was, in reality, an evolution that happened organically over about two millennia. Enough changed over that time, as Jason Kottke writes, that “it’s tough to see how the pictographic forms of the original script evolved into our letters; aside from the T and maybe M & O, there’s little resemblance.”

Baker’s design for this poster, notes Colossal’s Kate Sierzuputowski, “was created in association with his Writing Systems of the World chart which takes a look at 51 different writing systems from around the world.” All of the research for both those posters informs his video on the history of the alphabet, which looks at writing systems as they’ve developed across a variety of civilizations. You’ll notice that all of them respond in different ways to the needs of the times and places in which they arose, and some possess advantages that others don’t. (In Korea, where I live, one often hears the praises sung of the Korean alphabet, “the most scientific writing system in the world.”) But what the strengths of the descendant of modern Latin 2000 years on will be — and whether it will contain anything resembling emoji — not even the most astute linguist knows.

Related Content:

Now I Know My LSD ABCs: A Trippy Animation of the Alphabet

You Could Soon Be Able to Text with 2,000 Ancient Egyptian Hieroglyphs

The History of the English Language in Ten Animated Minutes

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Jodie Foster Teaches Filmmaking in Her First Online Course

FYI: If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

FYI: Jodie Foster has just rolled out a new online course on filmmaking over on MasterClass. In 18 video lessons, the two-time Oscar-winner guides “you through every step of the filmmaking process, from storyboarding to casting and camera coverage.” According to MasterClass, the course comes with “a downloadable workbook of lesson recaps and access to exclusive supplemental materials from Jodie’s archive.” Students will have “the chance to upload videos to receive feedback from peers and potentially Jodie herself!” You can enroll in Foster’s new class (which runs $90) here. You can also pay $180 to get an annual pass to all of MasterClass’ courses–which includes other filmmaking classes by Ken Burns, Martin Scorsese, Spike Lee, Werner Herzog and more.

Related Content:

Martin Scorsese Teaches His First Online Course on Filmmaking: Features 30 Video Lessons

Columbia U. Launches a Free Multimedia Glossary for Studying Cinema & Filmmaking

Read More...