Discover Kōlams, the Traditional Indian Patterns That Combine Art, Mathematics & Magic

Have accomplished abstract geometrical artists come out of any demographic in greater numbers than from the women of South Asia? Not when even the most demanding art-school curriculum can’t hope to equal the rigor of the kōlam, a complex kind of line drawing practiced by women everywhere from India to Sri Lanka to Malaysia to Thailand. Using humble materials like chalk and rice flour on the ground in front of their homes, they interweave not just lines, shapes, and patterns but religious, philosophical, and magical motifs as well — and they create their kōlams anew each and every day.

“Feeding A Thousand Souls: Kōlam” by Thacher Gallery at the University of San Francisco is licensed under CC BY-SA 2.0

“Taking a clump of rice flour in a bowl (or a coconut shell), the kōlam artist steps onto her freshly washed canvas: the ground at the entrance of her house, or any patch of floor marking an entrypoint,” writes Atlas Obscura’s Rohini Chaki.

“Working swiftly, she takes pinches of rice flour and draws geometric patterns: curved lines, labyrinthine loops around red or white dots, hexagonal fractals, or floral patterns resembling the lotus, a symbol of the goddess of prosperity, Lakshmi, for whom the kōlam is drawn as a prayer in illustration.”

Colorful Kolam — — Own work

Kōlams are thought to bring prosperity, but they also have other uses, such as feeding ants, birds, and other passing creatures. Chaki quotes University of San Francisco Theology and Religious Studies professor Vijaya Nagarajan as describing their fulfilling the Hindu “karmic obligation” to “feed a thousand souls.” Kōlams have also become an object of genuine interest for mathematicians and computer scientists due to their recursive nature: “They start out small, but can be built out by continuing to enlarge the same subpattern, creating a complex overall design,” Chaki writes. “This has fascinated mathematicians, because the patterns elucidate fundamental mathematical principles.”

“Kolam” by resakse is licensed under CC BY-ND 2.0

Like any traditional art form, the kōlam doesn’t have quite as many practitioners as it used to, much less practitioners who can meet the standard of mastery of completing an entire work without once standing up or even lifting their hand. But even so, the kōlam is hardly on the brink of dying out: you can see a few of their creators in action in the video at the top of the post, and the age of social media has offered kōlam creators of any age — and now even the occasional man — the kind of exposure that even the busiest front door could never match. Some who get into kōlams in the 21st century may want to create ones that show ever more complexity of geometry and depth of reference, but the best among them won’t forget the meaning, according to Chaki, of the form’s very name: beauty.

Read more about kōlams at Atlas Obscura.

Related Content:

Mathematics Made Visible: The Extraordinary Mathematical Art of M.C. Escher

New Iranian Video Game, Engare, Explores the Elegant Geometry of Islamic Art

The Complex Geometry of Islamic Art & Design: A Short Introduction

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...Mapping Emotions in the Body: A Finnish Neuroscience Study Reveals Where We Feel Emotions in Our Bodies

“Eastern medicine” and “Western medicine”—the distinction is a crude one, often used to misinform, mislead, or grind cultural axes rather than make substantive claims about different theories of the human organism. Thankfully, the medical establishment has largely given up demonizing or ignoring yogic and meditative mind-body practices, incorporating many of them into contemporary pain relief, mental health care, and preventative and rehabilitative treatments.

Hindu and Buddhist critics may find much not to like in the secular appropriation of practices like mindfulness and yoga, and they may find it odd that such a fundamental insight as the relationship between mind and body should ever have been in doubt. But we know from even a slight familiarity with European philosophy (“I think, therefore I am”) that it was from the Enlightenment into the 20th century.

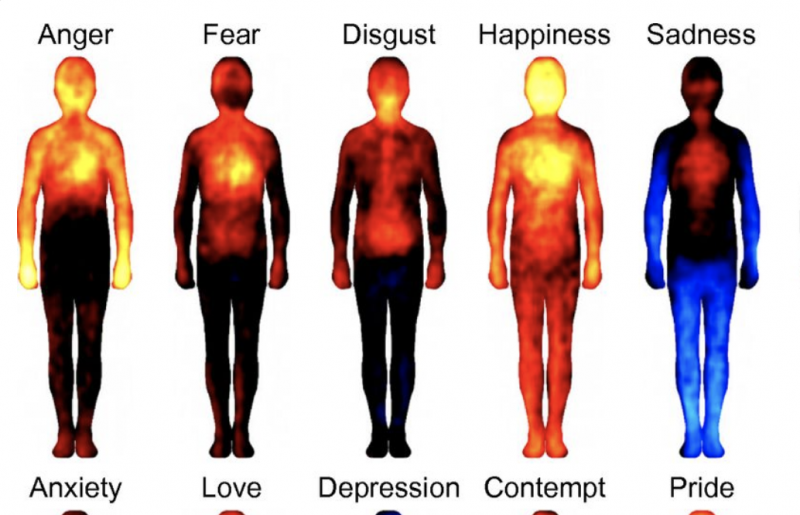

Now, says Riitta Hari, co-author of a 2014 Finish study on the bodily locations of emotion, “We have obtained solid evidence that shows the body is involved in all types of cognitive and emotional functions. In other words, the human mind is strongly embodied.” We are not brains in vats. All those colorful old expressions—“cold feet,” “butterflies in the stomach,” “chill up my spine”—named qualitative data, just a handful of the embodied emotions mapped by neuroscientist Lauri Nummenmaa and co-authors Riitta Hari, Enrico Glerean, and Jari K. Hietanen.

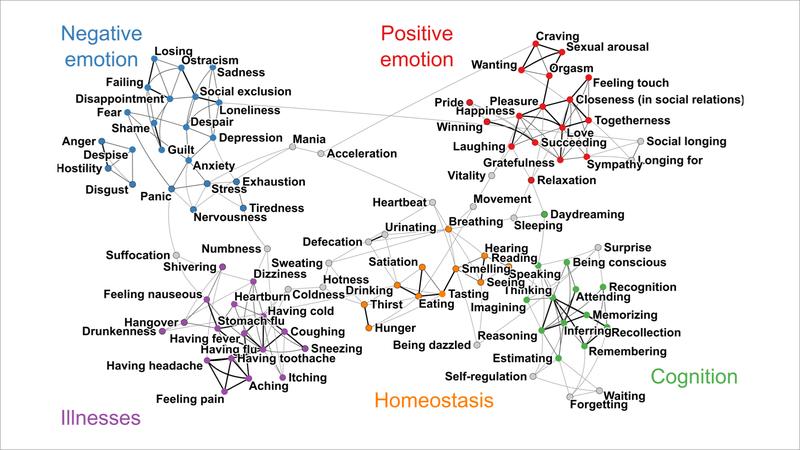

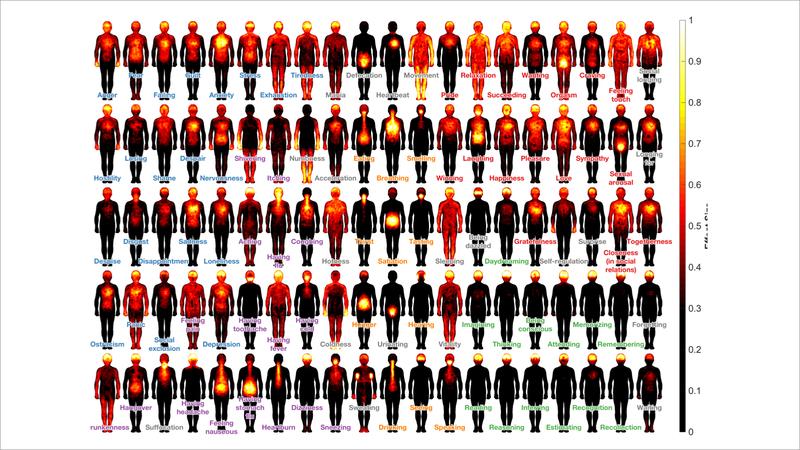

In their study, the researchers “recruited more than 1,000 participants” for three experiments, reports Ashley Hamer at Curiosity. These included having people “rate how much they experience each feeling in their body vs. in their mind, how good each one feels, and how much they can control it.” Participants were also asked to sort their feelings, producing “five clusters: positive feelings, negative feelings, cognitive processes, somatic (or bodily) states and illnesses, and homeostatic states (bodily functions).”

After making careful distinctions between not only emotional states, but also between thinking and sensation, the study participants colored blank outlines of the human body on a computer when asked where they felt specific feelings. As the video above from the American Museum of Natural History explains, the researchers “used stories, video, and pictures to provoke emotional responses,” which registered onscreen as warmer or cooler colors.

Similar kinds of emotions clustered in similar places, with anger, fear, and disgust concentrating in the upper body, around the organs and muscles that most react to such feelings. But “others were far more surprising, even if they made sense intuitively,” writes Hamer “The positive emotions of gratefulness and togetherness and the negative emotions of guilt and despair all looked remarkably similar, with feelings mapped primarily in the heart, followed by the head and stomach. Mania and exhaustion, another two opposing emotions, were both felt all over the body.”

The researchers controlled for differences in figurative expressions (i.e. “heartache”) across two languages, Swedish and Finnish. They also make reference to other mind-body theories, such as using “somatosensory feedback… to trigger conscious emotional experiences” and the idea that “we understand others’ emotions by simulating them in our own bodies.” Read the full, and fully illustrated, study results in “Bodily Maps of Emotions,” published by the National Academy of Sciences.

Related Content:

How Meditation Can Change Your Brain: The Neuroscience of Buddhist Practice

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Hear Raymond Carver’s Story “Fat” Read by Anne Enright

“Fat” is the first story in Raymond Carver’s 1976 collection Will You Please Be Quiet Please?. Thanks to The Guardian, you can hear the story read above by Irish author Anne Enright.

Find the story listed in our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Hear JG Ballard’s ‘My Dream of Flying to Wake Island,’ Read by William Boyd

Above, author William Boyd reads a JG Ballard story, ‘My Dream of Flying to Wake Island,’ which is “dominated by image and symbol rather than character and narrative.” The story was originally published in the 1978 sci-fi collection, Low-Flying Aircraft and Other Stories. The recording, which comes courtesy of The Guardian, will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Read More...Hear Italo Calvino’s “The Night Driver,” Read by Jeanette Winterson

Recorded by The Guardian, Jeanette Winterson reads Italo Calvino’s 1967 story “The Night Driver,” a story of two lovers falling out in the distant era ‘b4 mobile phones.’

This reading has been added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

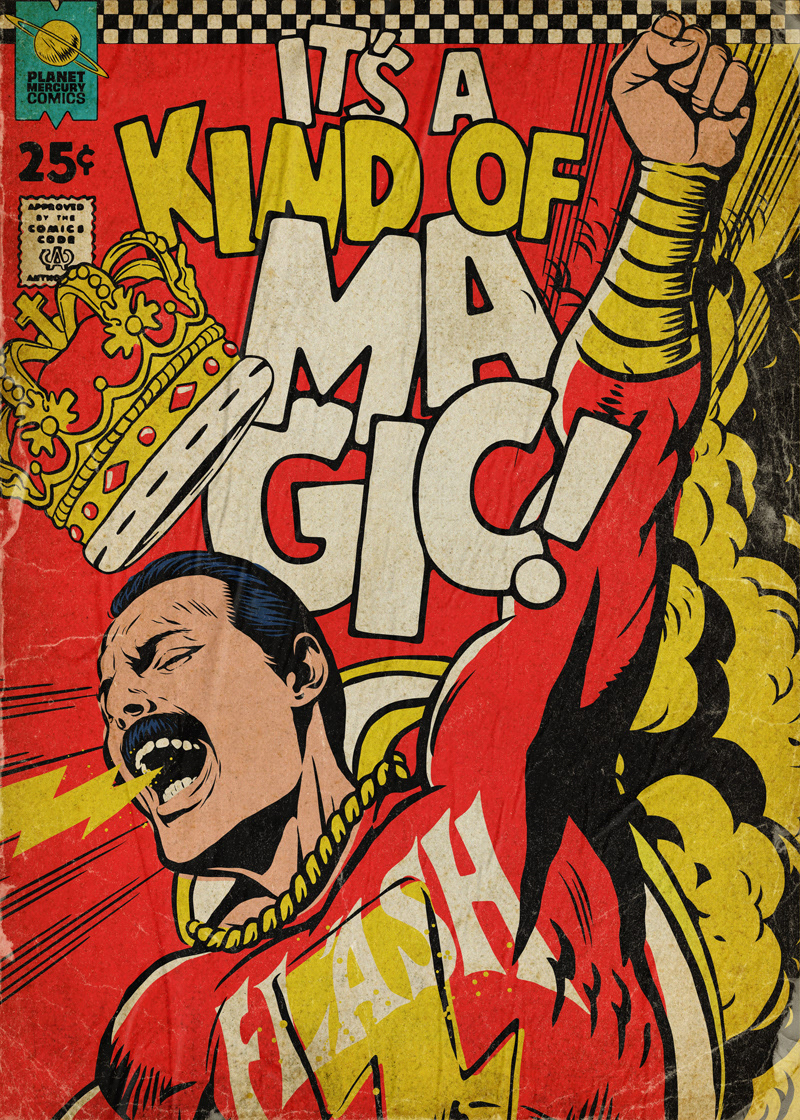

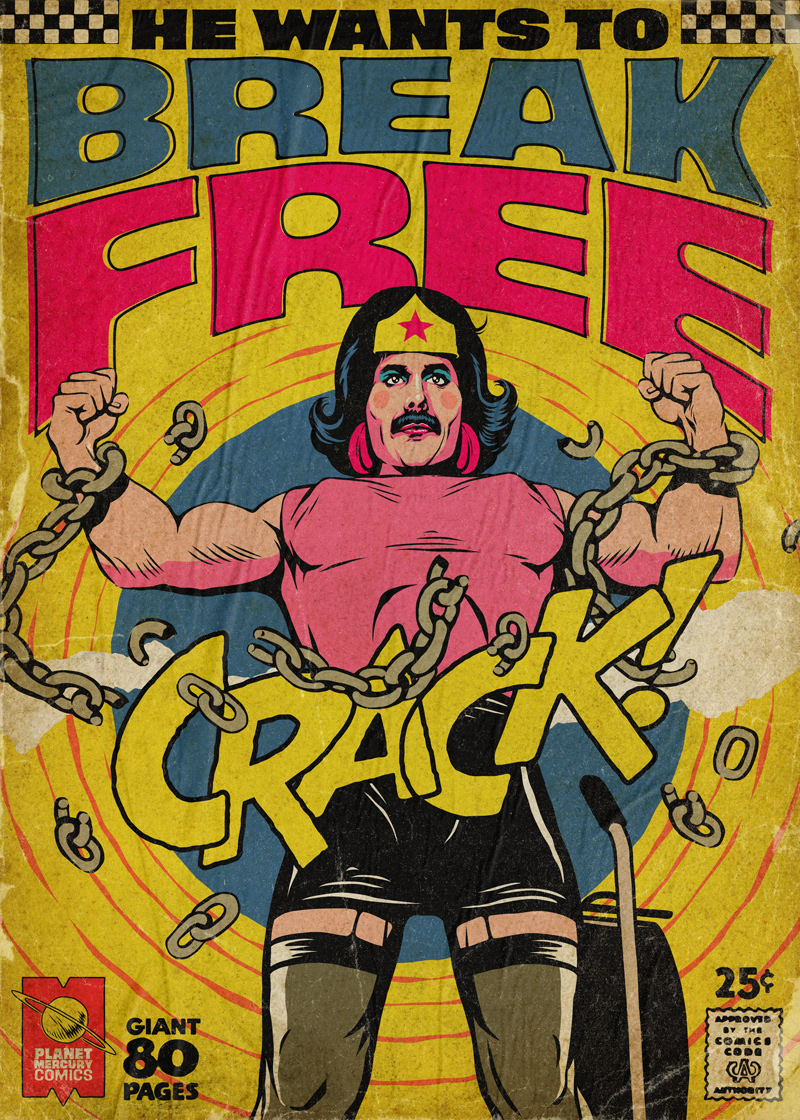

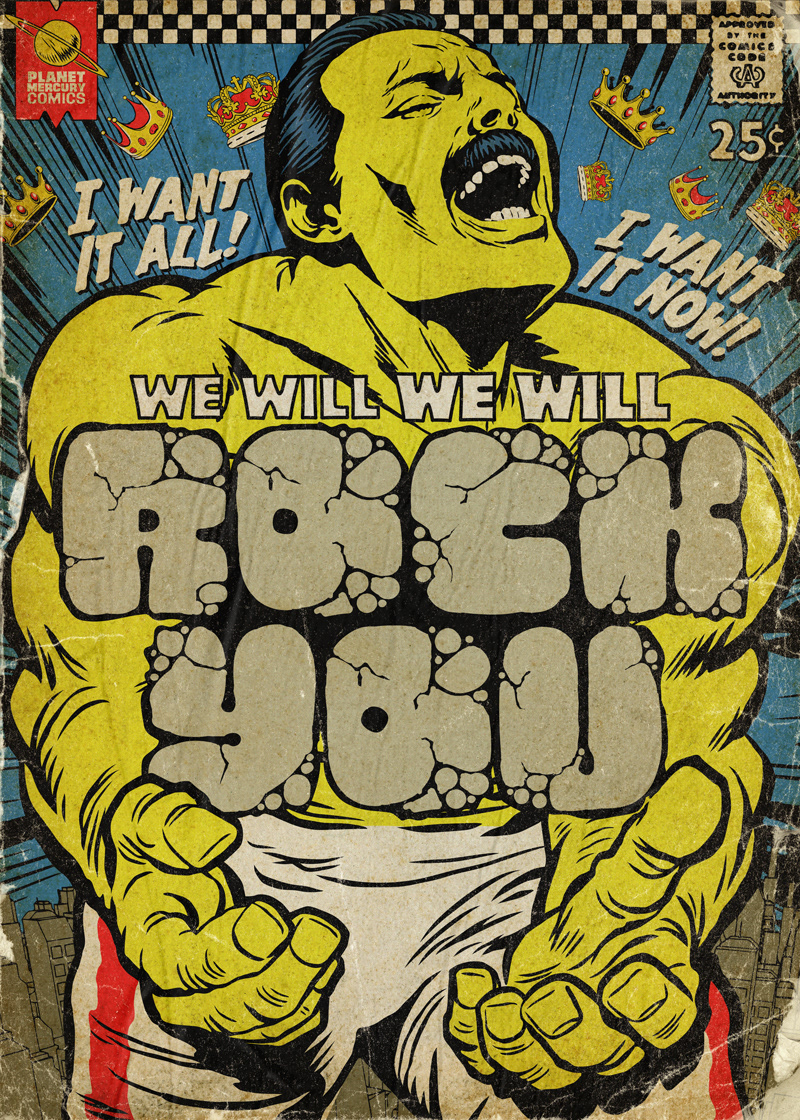

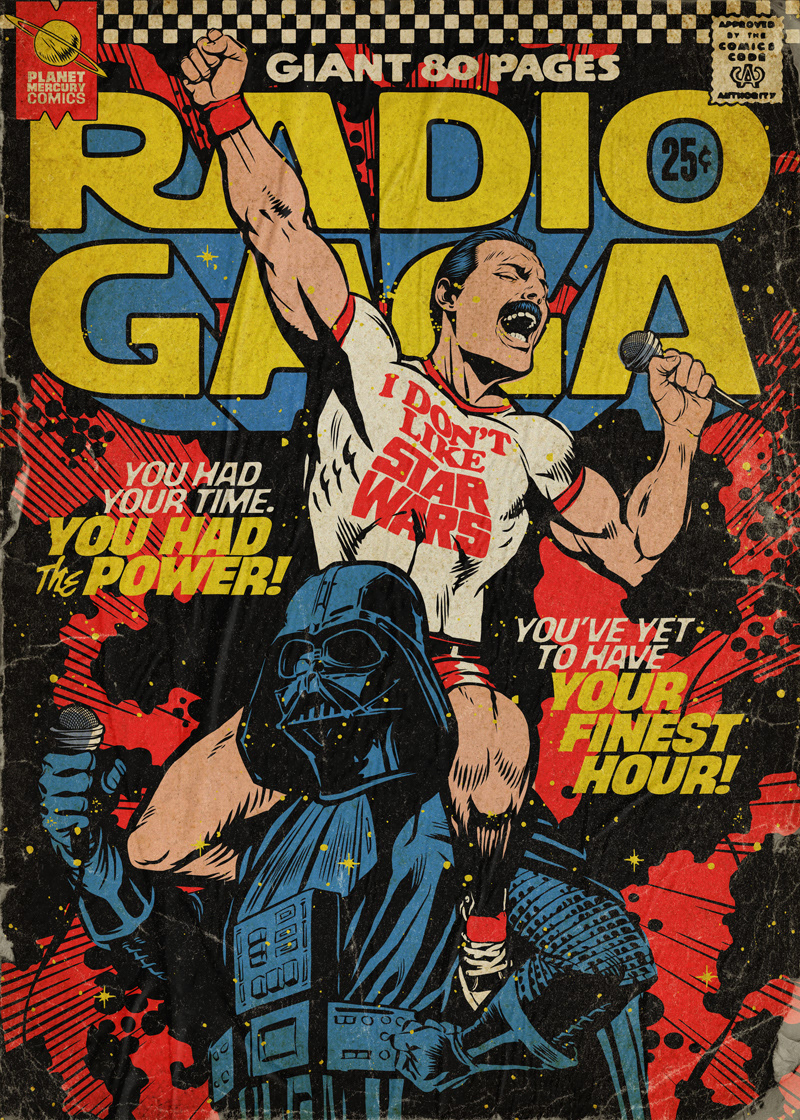

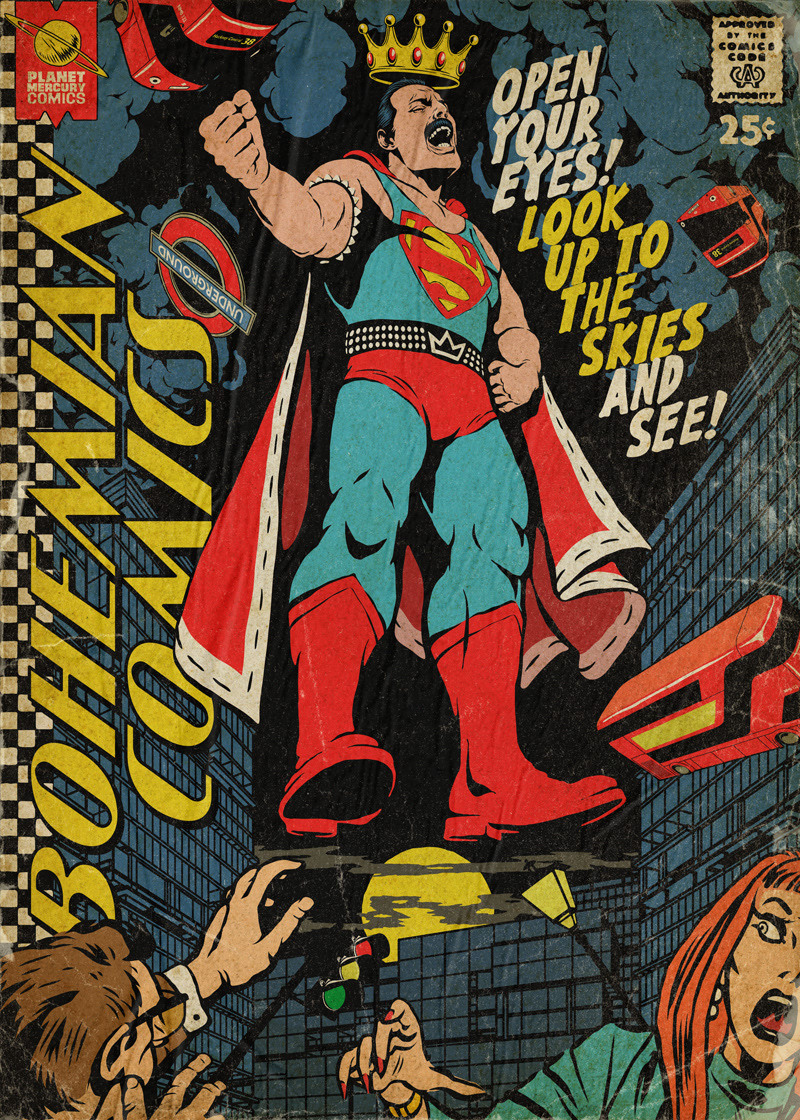

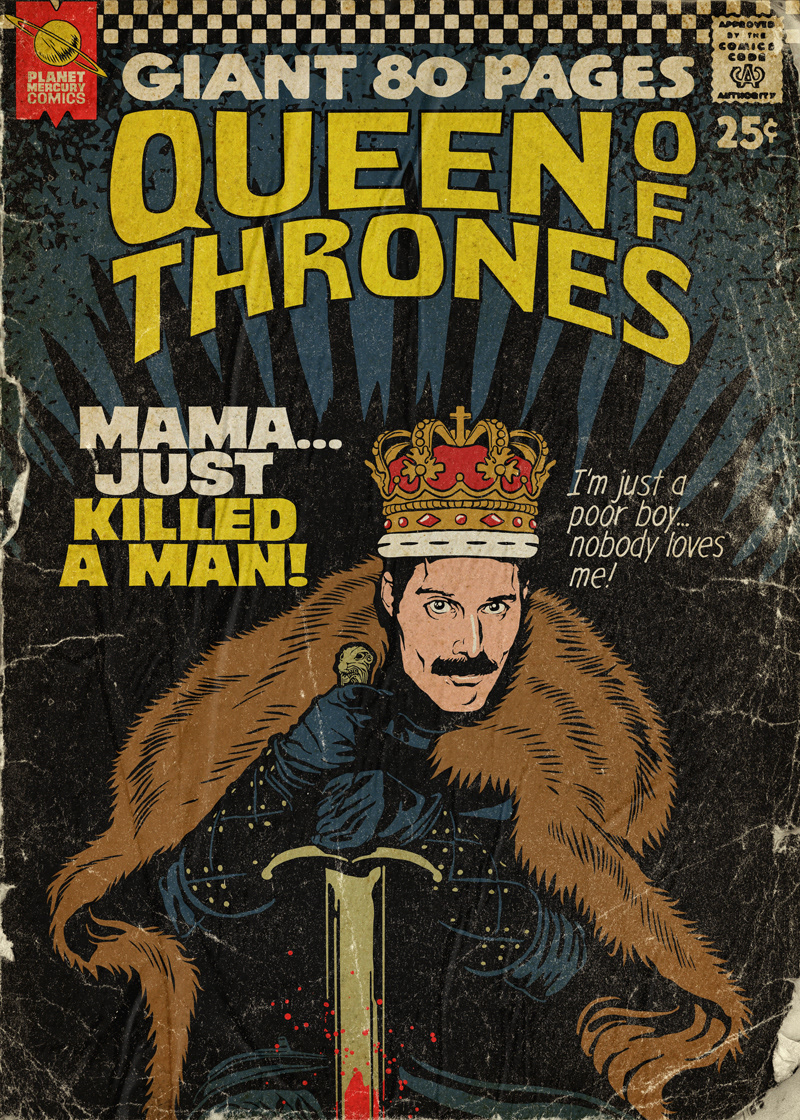

Read More...Freddie Mercury Reimagined as Comic Book Heroes

Pop culture thrives on superheroes, both fictional and real. This isn’t unique in human history. Read most any collection of ancient myth and literature and you’ll find the same. The demigods and chieftains beating their chests and talking trash in the Iliad, for example, remind me of macho professional wrestlers or characters in the Marvel and DC universes, cultural artifacts indebted in their various ways to classical legends. One thread runs through all of the epic tales of heroes and heroines: a seeming need to immortalize people who embody the qualities we most desire. Heroes may suffer for their tragic flaws, but that’s the price they pay for universal acclaim or an iron throne.

The traits ascribed to late modernity’s fictional heroes haven’t changed overmuch from the distant past—power, wit, agility, persistence, anger issues, spicy, complicated love lives…. But when it comes to the real people we admire—the celebrities who get the superhero treatment—creativity, style, and musical talent top the list. Why not?

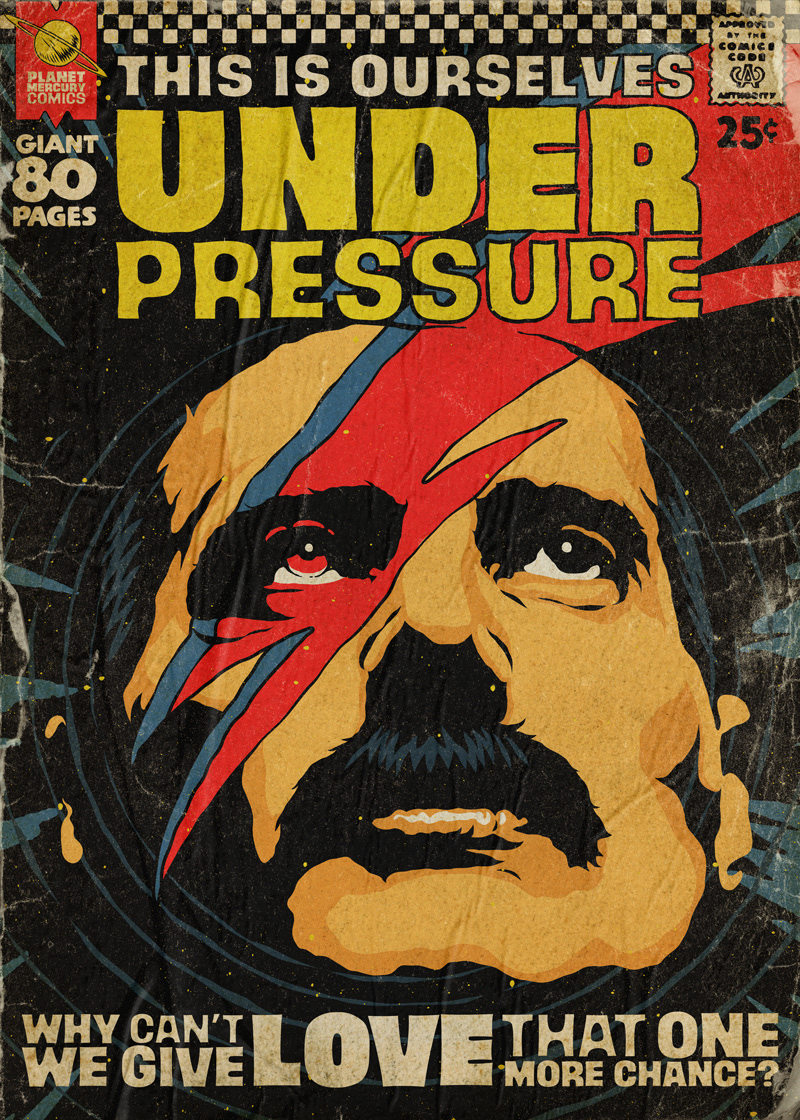

David Bowie’s larger-than-life personas surely deserve to live on, transmitted not only via his music but by way of his posthumous transformation into a series of pulp and comic heroes as imagined by screenwriter and designer Todd Alcott, who has given the same treatment to beloved musical characters like Prince and Bob Dylan.

Performing a similar service for Freddie Mercury, Brazilian artist Butcher Billy satisfies the cultural craving for demigods in his immortalization of Freddie Mercury as various heroes like The Hulk, Superman, and Shazam (or “Flash”); a contender for the Iron Throne; and himself: riding on Darth Vader’s shoulders, breaking free in housewife drag, and sporting Bowie’s Aladdin Sane lightning bolt. What are the superpowers of these super-Freddies? The usual smashing, punching, and flying, it seems, but also the essentials of his real-life power—an impossibly big personality, huge stage presence, personal magnetism, and a godlike force of a voice.

Add to these characteristics a unique talent for writing lyrics punchier than your favorite Twitter feed, and we have the makings of a modern epic giant with abilities that seemed to surpass those of mere mortals, with the swagger and ego to match. This tribute to Mercury is unabashed hero worship, turning the singer into an archetype. In the simple, bold, colorful lines of comic cover art we might just see that there’s a Freddie Mercury in all of us, wanting to break free, pump a fist in the air, and belt out our biggest feelings in capital letters and giant exclamation marks.

See more “Planet Mercury Comics” below and at Butcher Billy’s Behance site.

via Laughing Squid

Related Content:

David Bowie Songs Reimagined as Pulp Fiction Book Covers: Space Oddity, Heroes, Life on Mars & More

Scenes from Bohemian Rhapsody Compared to Real Life: A 21-Minute Compilation

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

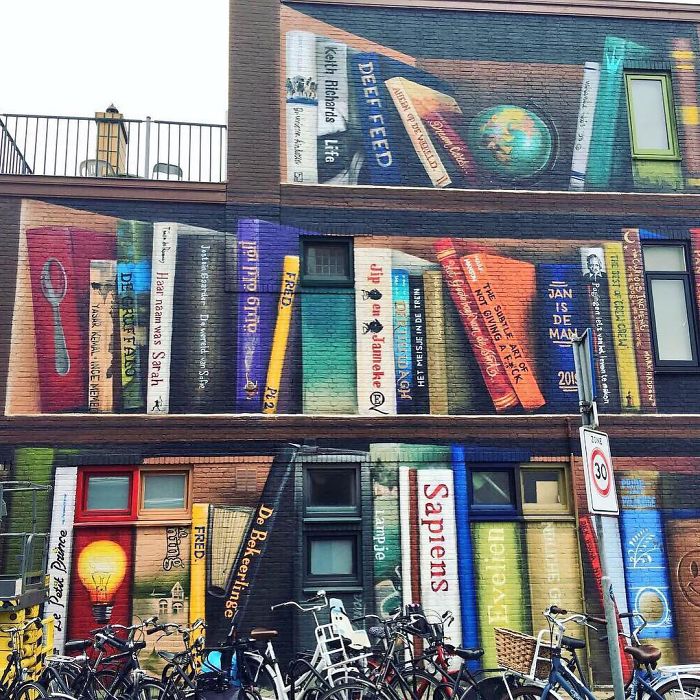

Read More...Street Art for Book Lovers: Dutch Artists Paint Massive Bookcase Mural on the Side of a Building

Bookcases are a great ice breaker for those who love to read.

What relief those shelves offer ill-at ease partygoers… even when you don’t know a soul in the room, there’s always a chance you’ll bond with a fellow guest over one of your hosts’ titles.

Occupy yourself with a good browse whilst waiting for someone to take the bait.

Now, with the aid of Dutch street artists Jan Is De Man and Deef Feed, some residents of Utrecht have turned their bookcases into street art, sparking conversation in their culturally diverse neighborhood.

De Man, whose close friends occupy the ground floor of a building on the corner of Mimosastraat and Amsterdam, had initially planned to render a giant smiley face on an exterior wall as a public morale booster, but the shape of the three-story structure suggested something a bit more literary.

The trompe-l’oeil Boekenkast (or bookcase) took a week to create, and features titles in eight different languages.

Look closely and you’ll notice both artists’ names (and a smiley face) lurking among the spines.

Design mags may make an impression by ordering books according to size and color, but this communal 2‑D boekenkast looks to belong to an avid and omnivorous reader.

Some English titles that caught our eye:

The Subtle Art of Not Giving a F*ck

Keith Richards’ autobiography Life

The Curious Incident of the Dog in the Nighttime

And a classy-looking hardbound Playboy collection that may or may not exist in real life.

(Readers, can you spot the other fakes?)

Boekenkast is the latest of a number of global bookshelf murals tempting literary pilgrims to take a selfie on the way to the local indie bookshop.

via Bored Panda

Related Content:

157 Animated Minimalist Mid-Century Book Covers

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in New York City this May for the next installment of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...9 Science-Fiction Authors Predict the Future: How Jules Verne, Isaac Asimov, William Gibson, Philip K. Dick & More Imagined the World Ahead

Pressed to give a four-word definition of science fiction, one could do worse than “stories about the future.” That stark simplification does the complex and varied genre a disservice, as the defenders of science fiction against its critics won’t hesitate to claim. And those critics are many, including most recently the writer Ian McEwan, despite the fact that his new novel Machines Like Me is about the introduction of intelligent androids into human society. Sci-fi fans have taken him to task for distancing his latest book from a genre he sees as insufficiently concerned with the “human dilemmas” imagined technologies might cause, but he has a point: set in an alternate 1982, Machines Like Me isn’t about the future but the past.

Then again, perhaps McEwan’s novel is about the future, and the androids simply haven’t yet arrived on our own timeline — or perhaps, like most enduring works of science fiction, it’s ultimately about the present moment. The writers in the sci-fi pantheon all combine a heightened awareness of the concerns of their own eras with a certain genuine prescience about things to come.

Writing in the early 1860s, Jules Verne imagined a suburbanized 20th century with gas-powered cars, electronic surveillance, fax machines and a population at once both highly educated and crudely entertained. Verne also included a simple communication system that can’t help but remind us of the internet we use today — a system whose promise and peril Neuromancer author William Gibson described on television more than 130 years later.

In the list below we’ve rounded up Verne and Gibson’s predictions about the future of technology and humanity along with those of seven other science-fiction luminaries. Despite coming from different generations and possessing different sensibilities, these writers share not just a concern with the future but the ability to express that concern in a way that still interests us, the denizens of that future. Or rather, something like that future: when we hear Aldous Huxley predict in 1950 that “during the next fifty years mankind will face three great problems: the problem of avoiding war; the problem of feeding and clothing a population of two and a quarter billions which, by 2000 A.D., will have grown to upward of three billions, and the problem of supplying these billions without ruining the planet’s irreplaceable resources,” we can agree with the general picture even if he lowballed global population growth by half.

In 1964, Arthur C. Clarke predicted not just the internet but 3D printers and trained monkey servants. In 1977, the more dystopian-minded J.G. Ballard came up with something that sounds an awful lot like modern social media. Philip K. Dick’s timeline of the years 1983 through 2012 includes Soviet satellite weapons, the displacement of oil as an energy source by hydrogen, and colonies both lunar and Martian. Envisioning the world of 2063, Robert Heinlein included interplanetary travel, the complete curing of cancer, tooth decay, and the common cold, and a permanent end to housing shortages. Even Mark Twain, despite not normally being regarded as a sci-fi writer, imagined a “ ‘limitless-distance’ telephone” system introduced and “the daily doings of the globe made visible to everybody, and audibly discussable too, by witnesses separated by any number of leagues.”

As much as the hits impress, they tend to be outnumbered in even science fiction’s greatest minds by the misses. But as you’ll find while reading through the predictions of these nine writers, what separates science fiction’s greatest minds from the rest is the ability to come up with not just interesting hits but interesting misses as well. Considering why they got right what they got right and why they got wrong what they got wrong tells us something about the workings of their imaginations, but also about the eras they did their imagining in — and how their times led to our own, the future to which so many of them dedicated so much thought.

- Jules Verne

- Mark Twain

- Aldous Huxley

- Arthur C. Clarke

- Robert Heinlein

- J.G. Ballard

- William Gibson

- Philip K. Dick

- Isaac Asimov (1964)

- Isaac Asimov (1983)

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

Read Hundreds of Free Sci-Fi Stories from Asimov, Lovecraft, Bradbury, Dick, Clarke & More

Free Science Fiction Classics on the Web: Huxley, Orwell, Asimov, Gaiman & Beyond

The Encyclopedia of Science Fiction: 17,500 Entries on All Things Sci-Fi Are Now Free Online

Isaac Asimov Recalls the Golden Age of Science Fiction (1937–1950)

The Art of Sci-Fi Book Covers: From the Fantastical 1920s to the Psychedelic 1960s & Beyond

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

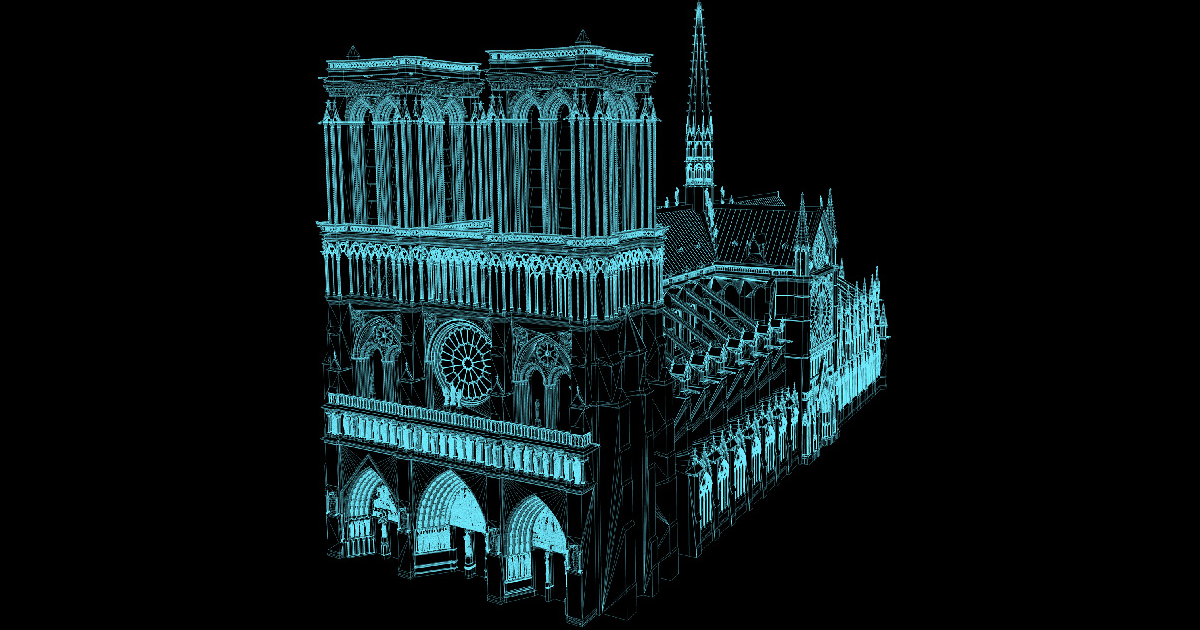

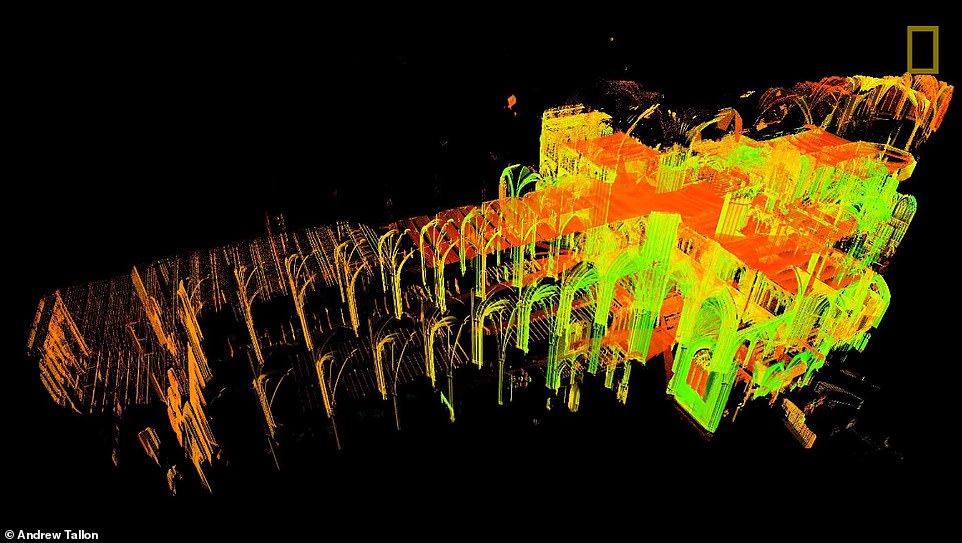

Read More...How Digital Scans of Notre Dame Can Help Architects Rebuild the Burned Cathedral

“Everyone helplessly watching something beautiful burn is 2019 in a nutshell,” wrote TV critic Ryan McGee on Twitter the day a significant portion of Notre Dame burned to the ground. He might have included 2018 in his metaphor, when Brazil’s National Museum was totally destroyed by fire. Before the Parisian monument caught flame, people watched helplessly as historic black churches burned in the U.S., and while the museum and cathedral fire were not the direct result of evil intent, in all of these events we witnessed the loss of sanctuaries, a word with both a religious meaning and a secular one, as columnist Jarvis DeBerry points out.

Sanctuaries are places where people, priceless artifacts, and knowledge should be “safe and protected,” supposedly institutional bulwarks against disorder and violence. They are both havens and potent symbols—and they are also physical spaces that can be rebuilt, if not replaced.

And 21st-century technology has made their rebuilding a far more collaborative and more precise affair. The reconstruction of churches in Louisiana can be funded through social media. The contents of the National Museum of Brazil can be recollected, virtually at least, through crowdsourcing and digital archives.

And the ravaged wood frame, roof, and spire of Notre Dame can be rebuilt, though never replaced, not only with millions in funding from Apple and fashion’s biggest houses, but with an exact 3D digital scan of the cathedral made in 2015 by Vassar art historian Andrew Tallon, who passed away last year from brain cancer. In the video at the top, see Tallon, then a professor at Vassar, describe his process, one driven by a lifelong passion for Gothic architecture, and especially for Notre Dame. A “former composer, would-be monk, and self-described gearhead,” wrote National Geographic in a 2015 profile of his work, Tallon brought a unique sensibility to the project.

His fascination with the spaces of Gothic cathedrals began with an investigation into their acoustic properties. He developed the idea of using laser scanners to create a digital replica of Notre Dame after studying at Columbia under art historian Stephen Murray, who tried and failed in 2001 to make a laser scan of a cathedral north of Paris. Fourteen years later, the technology finally caught up with the idea, which Tallon also improved on by attempting to reconstruct not only the structure, but also the methods the builders used to build it yet did not record in writing.

By examining how the cathedral moved when its foundations shifted or how it heated up or cooled down, Tallon could reveal “its original design and the choices that the master builder had to make when construction didn’t go as planned.” He took scans from “more than 50 locations around the cathedral—collecting more than one billion points of data.” All of the scans were knit together “to make them manageable and beautiful.” They are accurate to the millimeter, and as Wired reports, “architects now hope that Tallon’s scans may provide a map for keeping on track whatever rebuilding will have to take place.”

To learn even more about Tallon’s meticulous process than he reveals in the National Geographic video at the top, read his paper “Divining Proportions in the Information Age” in the open access journal Architectural Histories. We may not typically think of the digital world as much of a sanctuary, and maybe for good reason, but Tallon’s masterwork poignantly shows the importance of using its tools to record, document, and, if necessary, reconstruct the real-life spaces that meet our definitions of the term.

via the MIT Technology Review

Related Content:

Notre Dame Captured in an Early Photograph, 1838

A Virtual Time-Lapse Recreation of the Building of Notre Dame (1160)

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Do Ethicists Behave Any Better Than the Rest of Us?: Here’s What the Research Shows

We’ve heard about the lawyering fool who has him- or herself for a client. The old proverb does not mean to say that lawyers are especially scrupulous, only that the intricacies of the law are best left to the professionals, and that a personal interest in a case muddies the waters. That may go double or triple for doctoring, though doctors don’t have to bear the lawyer’s social stigma.

But can we reasonably expect doctors to live healthier lives than the general population? What about other professions that seem to entail a rigorous code of conduct? Many people have lately been disabused of the idea that clergy or police have any special claim to moral upstandingness (on the contrary)….

What about ethicists? Should we have high expectations of scholars in this subset of philosophy? There are no clever sayings, no genre of jokes at their expense, but there are a few academic studies asking some version of the question: does studying ethics make a person more ethical?

You might suspect that it does not, if you’re a cynic—or the answer might surprise you!.… Put more precisely, in a recent study—“The Moral Behavior of Ethics Professors,” published in Philosophical Psychology this year—the “open but highly relevant question” under consideration is “the relation between ethical reflection and moral action.”

The paper’s authors, professor Johannes Wanger of Austria’s University of Graz and graduate student Philipp Schönegger from the University of St. Andrews in Scotland, surveyed 417 professors in three categories, reports Olivia Goldhill at Quartz: “ethicists (philosophers focused on ethics), philosophers focused on non-ethical subjects, and other professors.” The paper surveyed only German-speaking scholars, replicating the methods of a 2013 study focused on English-speaking professors.

The questions asked touched on “a range of moral topics, including organ donation, charitable giving, and even how often they called their mother.” After assessing general views on the subjects, the authors “then asked the professors about their own behavior in each category.” We must assume a base level of honesty among the respondents in their self-reported answers.

The results: “the researchers found no significant difference in moral behavior” between those who make it their business to study ethics and those who study other things. For example, the majority of the academics surveyed agreed that you should call your mother: at 75% of non-philosophers, 70% of non-ethicists, and 65% of ethicists (whose numbers might be lower here because other issues could seem weightier to them by comparison).

When it comes to picking up the phone to call mom at least twice a month, the numbers were consistently high, but ethicists did not rate particularly higher at 87% versus 81% of non-ethicist philosophers and 89% of others. The subject of charitable giving may warrant more scrutiny. Ethicists recommended donating an average of 6.9% of one’s annual salary, where non-ethicists said 4.6% was enough and others said 5.1%. The numbers for all three groups, however, hover around four and half percent.

One notable exception to this trend: vegetarianism: “Ethicists were both more likely to say that it was immoral to eat meat, and more likely to be vegetarians themselves.” But on average, scholars of ethical behavior do not seem to behave better than their peers. Should we be surprised at this? Eric Schwitzgebel, a philosophy professor at University of California, Riverside, and one of the authors of original, 2013 study, finds the results upsetting.

Using the example of a hypothetical professor who makes the case for vegetarianism, then heads to the cafeteria for a burger, Schwitzgebel refers to modern-day philosophical ethics as “cheeseburger ethics.” Of his work on the behavior of ethicists with Stetson University’s Joshua Rust, he writes, “never once have we found ethicists as a whole behaving better than our comparison groups of other professors…. Nonetheless, ethicists do embrace more stringent moral norms on some issues.”

Should philosophers who hold such views aspire to be better? Can they be? Schönegger and Wagner frame the issue upfront in their recent version of the study (which you can read in full here), with a quote from the German philosopher Max Scheler: “signposts do not walk in the direction they point to.” Ethicists draw conclusions about ideals of human behavior using the tools of philosophy. They show the way but should not personally set themselves up as exemplars or role-models. As one high-profile case of a very badly-behaved ethicist suggests, this might not do the profession any favors.

Schwitzgebel is not content with this answer. The problem, he writes at Aeon, may be professionalization itself, imposing an unnatural distance between word and deed. “I’d be suspicious of any 21st-century philosopher who offered up her- or himself as a model of wise living,” he writes, “This is no longer what it is to be a philosopher—and those who regard themselves as wise are in any case almost always mistaken. Still, I think, the ancient philosophers got something right that the cheeseburger ethicist gets wrong.”

The “something wrong” is a laissez-faire comfort with things as they are. Leaving ethics to the realm of theory takes away a sense of moral urgency. “A full-bodied understanding of ethics requires some living,” Schwitzgebel writes. It might be easier for philosophers to avoid aiming for better behavior, he implies, when they are only required, and professionally rewarded, just to think about it.

Related Content:

Oxford’s Free Course A Romp Through Ethics for Complete Beginners Will Teach You Right from Wrong

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...