Pretty Much Pop #16 Considers the Sitcom “Friends” 25 Years Later

Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt examine the conventions, techniques, and staying power of the beloved ’90s sitcom. Are we supposed to identify with, or idolize, or merely like these people? What makes the formula work, did it sustain itself over its 10-year run, was it successfully replicated (like by How I Met Your Mother or by Chuck Lorre?), and what parts haven’t aged well?

We reviewed a ton of articles to prep for this that you may want to read:

- “What the Critics Said About the 1994 Debut of Friends” by Margaret Lyons

- “‘Friends’ Is Turning 25. Here’s Why We Can’t Stop Watching It” by Wesley Morris

- “Why ‘Friends’ Is Still the World’s Favourite Sitcom, 25 Years On” by J.T. (at The Economist)

- “‘Friends’ Is Getting Old. Its Fans Have Never Been Younger” by Andrew Dalton

- “Friends Was a Great Show — That Just Happened to Ruin TV Comedy” by Emily Todd VanDerWerff

- “‘Friends’ Hasn’t Aged Well” by Scaachi Koul

- “‘Fat Monica’ Is the Ghost That Continues to Haunt Friends 25 Years Later” from Entertainment Weekly (no byline)

- “Friends at 25: Is the Sitcom Really as Problematic as People Say? Stylist Investigates” by Kayleigh Dray

- “Don’t Knock Friends. It’s Still Relevant, and Progressive, Too” by Sarah Gosling

- “Why ‘Friends’ Won’t Get Rebooted” by Saul Austerlitz

- “A Party Room and a Prison Cell Inside the Friends Writers’ Room” by Saul Austerlitz

- “Television Without Pity” by Christopher Nixon

- “‘Friends’ Creator Regrets One Of The Show’s Problematic Elements” by Nick Levine

This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Read More...Do Octopi Dream? An Astonishing Nature Documentary Suggests They Do

With regard to the sleeping and waking of animals, all creatures that are red-blooded and provided with legs give sensible proof that they go to sleep and that they waken up from sleep; for, as a matter of fact, all animals that are furnished with eyelids shut them up when they go to sleep.

Furthermore, it would appear that not only do men dream, but horses also, and dogs, and oxen; aye, and sheep, and goats, and all viviparous quadrupeds; and dogs show their dreaming by barking in their sleep. With regard to oviparous animals we cannot be sure that they dream, but most undoubtedly they sleep.

And the same may be said of water animals, such as fishes, molluscs, crustaceans, to wit crawfish and the like. These animals sleep without doubt, although their sleep is of very short duration. The proof of their sleeping cannot be got from the condition of their eyes-for none of these creatures are furnished with eyelids—but can be obtained only from their motionless repose.

-Aristotle, The History of Animals, Book IV, Part 10,350 B.C.E

2,369 years later, Marine Biologist David Scheel, a professor at Alaska Pacific University, witnessed a startling event, above, that allowed him to expand on Aristotle’s observations, at least as far as eight-armed cephalopod mollusks—or octopi—are concerned

Apparently, they dream.

Scheel, whose specialties include predator-prey ecology and cephalopod biology, is afforded an above-average amount of quality time with these alien animals, courtesy of Heidi, an octopus cyanea (or day octopus) who inhabits a large tank of salt water in his living room.

Scheel’s usual beat is cold water species such as the giant Pacific octopus. Heidi, who earned her name by shyly sticking to the farthest recesses of her artificial environment upon arrival, belongs to a warmer water species who are active during the day. Very active. Once she realized that Scheel and his 16-year-old daughter, Laurel, were instruments of food delivery, she came out of her shell, so to speak.

The hours she keeps affords her plenty of stimulating playtime with Laurel, who’s thrilled to have an animal pal who’s less ambivalent than her pet goldfish and outdoor rabbit.

Meanwhile, the co-housing arrangement provides Professor Scheel with an intimacy that’s impossible to achieve in the lab.

He was not expecting the astonishing nocturnal behavior he recorded, above, for the hour-long PBS Nature documentary Octopus: Making Contact.

As Heidi slept, she changed colors, rapidly cycling through patterns that correspond to her hunting practices. Scheel walks viewers through:

So, here she’s asleep, she sees a crab, and her color starts to change a little bit.

Then she turns all dark.

Octopuses will do that when they leave the bottom.

This is a camouflage, like she’s just subdued a crab and now she’s going to sit there and eat it and she doesn’t want anyone to notice her.

It’s a very unusual behavior to see the color come and go on her mantel like that.

I mean, just to be able to see all the different color patterns just flashing, one after another.

You don’t usually see that when an animal is sleeping.

This really is fascinating.

But, yeah, if she’s dreaming, that’s the dream.

As dreams go, the narrative Scheel supplies for Heidi seems extremely mundane. Perhaps somewhere out on a coral reef, another octopus cyanea is dreaming she’s trapped inside a small glass room, feasting on easily gotten crab and occasionally crawling up a teenaged human’s arm.

Watch the full episode for free through October 31 here.

via Laughing Squid/This is Colossal

Related Content:

Every U.S. Vice President with an Octopus on His Head: Kickstart The Veeptopus Book

Environment & Natural Resources: Free Online Courses

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC tonight, Monday, October 7 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates the art of Aubrey Beardsley. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...The First Music Streaming Service Was Invented in 1881: Discover the Théâtrophone

Every living adult has witnessed enough technological advancement in their lifetime to marvel at just how much has changed, and digital streaming and telecommunications happen to be areas where the most revolutionary change seems to have taken place. We take for granted that the present resembles the past not at all, and that the future will look unimaginably different. So the narrative of linear progress tells us. But that story is never as triumphantly simple as it seems.

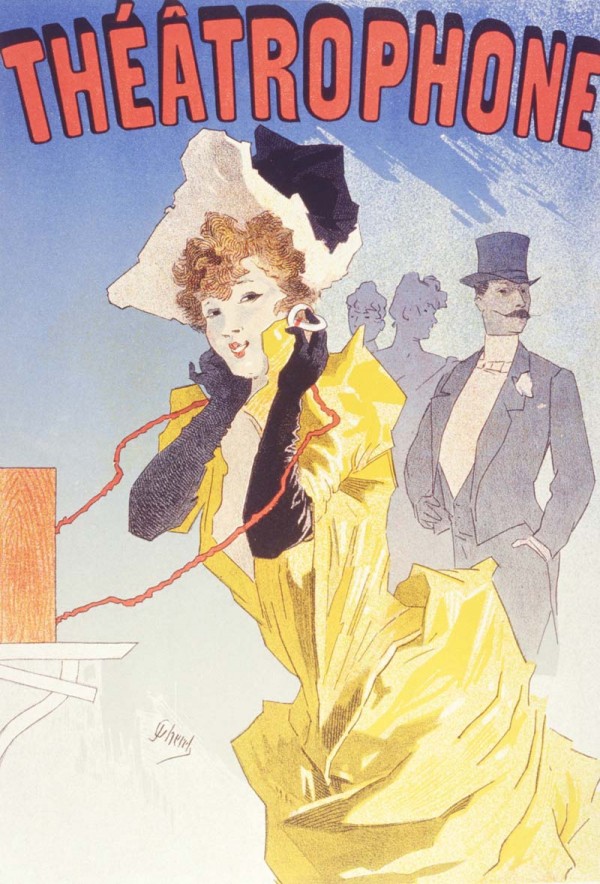

In one salient counterexample, we find that not only did livestreaming music and news exist in theory long before the internet, but it existed in actual practice—at the very dawn of recording technology, telephony, and general electrification. First developed in France in 1881 by inventor Clement Ader, who called his system the Théâtrophone, the device allowed users to experience “the transmission of music and other entertainment over a telephone line,” notes the site Bob’s Old Phones, “using very sensitive microphones of [Ader’s] own invention and his own receivers.”

The pre-radio technology was ahead of its time in many ways, as Michael Dervan explains at The Irish Times. The Théâtrophone “could transmit two-channel, multi-microphone relays of theatre and opera over phone lines for listening on headphones. The use of different signals for the two ears created a stereo effect.” Users subscribed to the service, and it proved popular enough to receive an entry in the 1889 edition of The Electrical Engineer reference guide, which defined it as “a telephone by which one can have soupçons of theatrical declamation for half a franc.”

In 1896 “the Belle Epoque pop artist Jules Cheret immortalized the theatrophone,” writes Tanya Basu at Mental Floss, “in a lithograph featuring a woman in a yellow dress, grinning as she presumably listened to an opera feed.” Victor Hugo got to try it out. “It’s very strange,” he wrote. “It starts with two ear muffs on the wall, and we hear the opera; we change earmuffs and hear the French Theatre, Coquelin. And we change again and hear the Opera Comique. The children and I were delighted.”

Though The Electrical Engineer also called it “the latest thing to catch [Parisians’] ears and their centimes,” the innovation had already by that time spread elsewhere in Europe. Inventor Tivador Puskas created a “streaming” system in Budapest called Telefon Hermondo (Telephone Herald), Bob’s Old Phones points out, “which broadcast news and stock market information over telephone lines.” Unlike Ader’s system, subscribers could “call in to the telephone switchboard and be connected to the broadcast of their choice. The system was quite successful and was widely reported overseas.”

The mechanism was, of course, quite different from digital streaming, and quite limited by our standards, but the basic delivery system was similar enough. A third such service worked a little differently. The Electrophone system, formed in London in 1884, combined its predecessors’ ideas: broadcasting both news and musical entertainment. Playback options were expanded, with both headphones and a speaker-like megaphone attachment.

Additionally, users had a microphone so that they could “talk to the Central Office and request different programs.” The addition of interactivity came at a premium. “The Electrophone service was expensive,” writes Dervan, “£5 a year at a time when that sum would have covered a couple months rent.” Additionally, “the experience was communal rather than solitary.” Subscribers would gather in groups to listen, and “some of the photographs” of these sessions resemble “images of addicts in an old-style opium den”—or of Victorians gathered at a séance.

The company later gave recuperating WWI servicemen access to the service, which heightened its profile. But these early livestreaming services—if we may so call them—were not commercially viable, and “radio killed the venture off in the 1920s” with its universal accessibility and appeal to advertisers and governments. This seeming evolutionary dead end might have been a distant ancestor of streaming live concerts and events, though no one could have foreseen it at the time. No one save science fiction writers.

Edward Bellamy’s 1888 utopian novel Looking Backward imagined a device very like the Théâtrophone in his vision of the year 2000. And in 1909, E.M. Forster drew on early streaming services and other early telecommunications advances for his visionary short story “The Machine Stops,” which extrapolated the more isolating tendencies of the technology to predict, as playwright Neil Duffield remarks, “the internet in the days before even radio was a mass medium.”

Related Content:

The History of the Internet in 8 Minutes

Hear the First Recording of the Human Voice (1860)

How an 18th-Century Monk Invented the First Electronic Instrument

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Jimi Hendrix Wreaks Havoc on the Lulu Show, Gets Banned From the BBC (1969)

Can you imagine Jimi Hendrix singing a duet with Lulu? Well, neither could Hendrix. So when the iconoclastic guitar player showed up with his band at the BBC studios in London on January 4, 1969 to appear on Happening for Lulu, he was horrified to learn that the show’s producer wanted him to sing with the winsome star of To Sir, With Love. The plan called for The Jimi Hendrix Experience to open their set with “Voodoo Child (Slight Return)” and then play their early hit “Hey Joe,” with Lulu joining Hendrix onstage at the end to sing the final bars with him before segueing into her regular show-closing number. “We cringed,” writes bassist Noel Redding in his memoir, Are You Experienced? The Inside Story of The Jimi Hendrix Experience.

Redding describes the scene that he, Hendrix, and drummer Mitch Mitchell walked into that day as being “so straight it was only natural that we would try to combat that atmosphere by having a smoke in our dressing room.” He continues:

In our haste, the lump of hash got away and slipped down the sink drainpipe. Panic! We just couldn’t do this show straight–Lulu didn’t approve of smoking! She was then married to Maurice Gibb of the Bee Gees, whom I’d visited and shared a smoke with. I could always tell Lulu was due home when Maurice started throwing open all the windows. Anyway, I found a maintenance man and begged tools from him with the story of a lost ring. He was too helpful, offering to dismantle the drain for us. It took ages to dissuade him, but we succeeded in our task and had a great smoke.

When it was time for The Jimi Hendrix Experience to go on camera, they were feeling fairly loose. They tore through “Voodoo Child” and then the program cut to Lulu, who was squeezed awkwardly into a chair next to an audience member in the front row. “That was really hot,” she said. “Yeah. Well ladies and gentlemen, in case you didn’t know, Jimi and the boys won in a big American magazine called Billboard the group of the year.” As Lulu spoke a loud shriek of feedback threw her off balance. Was it an accident? Hendrix, of course, was a pioneer in the intentional use of feedback. A bit flustered, she continued: “And they’re gonna sing for you now the song that absolutely made them in this country, and I’d love to hear them sing it: ‘Hey Joe.’ ”

The band launched into the song, but midway through–before Lulu had a chance to join them onstage–Hendrix signaled to the others to quit playing. “We’d like to stop playing this rubbish,” he said, “and dedicate a song to the Cream, regardless of what kind of group they may be in. We dedicate this to Eric Clapton, Ginger Baker and Jack Bruce.” With that the band veered off into an instrumental version of “Sunshine of Your Love” by the recently disbanded Cream. Noel Redding continues the story:

This was fun for us, but producer Stanley Dorfman didn’t take it at all well as the minutes ticked by on his live show. Short of running onto the set to stop us or pulling the plug, there was nothing he could do. We played past the point where Lulu might have joined us, played through the time for talking at the end, played through Stanley tearing his hair, pointing to his watch and silently screaming at us. We played out the show. Afterwards, Dorfman refused to speak to us but the result is one of the most widely used bits of film we ever did. Certainly, it’s the most relaxed.

The stunt reportedly got Hendrix banned from the BBC–but it made rock and roll history. Years later, Elvis Costello paid homage to Hendrix’s antics when he performed on Saturday Night Live. You can watch The Stunt That Got Elvis Costello Banned From SNL here.

Note: An earlier version of this post appeared on our site in 2012.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related content:

The Stunt That Got Elvis Costello Banned From Saturday Night Live (1977)

Jimi Hendrix Unplugged: Two Great Recordings of Hendrix Playing Acoustic Guitar

Read More...Is the Live Music Experience Irreplaceable? Pretty Much Pop #11

Surely technological advances have made it unnecessary to ever leave the house, right? Is there still a point in seeing live people actually doing things right in front of you?

Dave Hamilton (Host of Gig Gab, Mac Geek Gab) joins Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt to discuss what’s so damn cool about live music (and theater), the alternatives (live-streamed-to-theaters or devices, recorded for TV, VR), why tickets are so expensive, whether tribute bands fulfill our needs, the connection between live music and drugs, singing along to the band, and more.

We touch on Rush (and their tribute Lotus Land), Damien Rice, Todd Rundgren, The Who, Cop Rock, Bat out of Hell: The Musical, Hedwig and the Angry Inch, the filmed Shrek The Musical, and Rifftrax Live.

We used some articles to feed this episode, though we didn’t really bring them up:

- “Nielsen Releases In-Depth Statistics on Live Music Behavior” by Dan Rys

- “7 Predications on the Future of Live Music” by Jason Donnelly

- “Live at Home: how to see concerts every day without leaving your couch” by Noel Murray

- “Broadcasts Of ‘Live’ Theater And Opera Are Terrific In Their Own Way” by Maureen Dezell

You know Mark also runs a music podcast, right? Check out Erica doin’ her fiddlin’ and singin’. Listen to Mark’s mass of tunes. Here’s Dave singing and drumming some Badfinger live with his band Fling, and here’s Mark live singing “The Grinch.”

This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Read More...Watch the Completely Unsafe, Vertigo-Inducing Footage of Workers Building New York’s Iconic Skyscrapers

Would anyone in their right mind sign up for a job that had a high risk of mortality/disability? Or a job where red hot metal is being hurled directly at your face? Back in the 1920s this was the lot of the men who built New York’s skyline, the men who constructed the Chrysler Building and the Empire State, giant phallic symbols of America’s burgeoning wealth and power.

In this short clip (remastered and quite decently colorized) from the Smithsonian Channel, we get a brief glimpse of the perils encountered daily on the building site. Nicknamed “roughnecks,” the narrator points out that they work without harnesses, safety ropes, or hard hats. Red hot rivets are thrown at men on the metal beams higher up and they are meant to catch them with what looks like a tin funnel. You can see the thinnest of ropes used to lift the now-iconic stainless steel art-deco eagles into place by men weary felt hats and no gloves.

The workers came from Europe, many who had trained on ships. Some came from Montreal’s Kahnawake reservation. The latter, known as Iron Walkers, were Mohawk, known for working fearlessly at great heights.

“A lot of people think Mohawks aren’t afraid of heights; that’s not true,” Kyle Karonhiaktatie Beauvais said in 2002. “We have as much fear as the next guy. The difference is that we deal with it better.”

Much of this work was documented by photographer Lewis Hine, who captured a mix of brute strength and gravity defying courage along with private moments of rest, catching a smoke or taking lunch. You can see many of his famous photos in this clip:

The Chrysler Building was completed in 1930, and reached a height of 1,046 feet (319 m), featuring 77 floors. It held its fame as the world’s tallest building for only 11 months. In 1931 workers completed the Empire State Building, standing at 1,454 feet (443.2 m) and housing 102 floors. (That’s dinky compared to the current record-holder: Dubai’s Burj Khalifa, which stands at 2,722 feet (829.8 m)).

Heads up: The Smithsonian Channel clip has some of the worst examples of YouTube comments among the videos we’ve highlighted over the year, as if people still don’t work in terrible and unsafe conditions in order to feed their families and pay rent. And look! Here’s a guy who walks out onto the Chrysler eagle just for fun. Don’t say we didn’t warn you:

Related Content:

Paris, New York & Havana Come to Life in Colorized Films Shot Between 1890 and 1931

Famous Architects Dress as Their Famous New York City Buildings (1931)

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Read More...A Digital Animation Compares the Size of Trees: From the 3‑Inch Bonsai, to the 300-Foot Sequoia

It took about 110 days to put together. A digital animation comparing the size of trees, from a miniature 3‑inch bonsai, to a sequoia soaring more than 300 feet high. Some trees are smaller than blades of grass. Others bigger than the Statue of Liberty. A lot fall somewhere between.

If you would like to sign up for Open Culture’s free email newsletter, please find it here. It’s a great way to see our new posts, all bundled in one email, each day.

If you would like to support the mission of Open Culture, consider making a donation to our site. It’s hard to rely 100% on ads, and your contributions will help us continue providing the best free cultural and educational materials to learners everywhere. You can contribute through PayPal, Patreon, and Venmo (@openculture). Thanks!

Related Content:

3,000-Year-Old Olive Tree on the Island of Crete Still Produces Olives Today

Read More...Mister Rogers Creates a Prime Time TV Special to Help Parents Talk to Their Children About the Assassination of Robert F. Kennedy (1968)

Nearly three minutes into a patient blow-by-blow demonstration of how breathing works, Fred Rogers’ timorous hand puppet Daniel Striped Tiger surprises his human pal, Lady Aberlin, with a whammy: What does assassination mean?

Her answer, while not exactly Webster-Merriam accurate, is both considered and age-appropriate. (Daniel’s forever-age is somewhere in the neighborhood of four.)

The exchange is part of a special primetime episode of Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood, that aired just two days after Senator Robert F. Kennedy’s assassination.

Rogers, alarmed that America’s children were being exposed to unfiltered descriptions and images of the shocking event, had stayed up late to write it, with the goal of helping parents understand some of the emotions their children might be experiencing in the aftermath:

I’ve been terribly concerned about the graphic display of violence which the mass media has been showing recently. And I plead for your protection and support of your young children. There is just so much that a very young child can take without it being overwhelming.

Rogers was careful to note that not all children process scary news in the same way.

To illustrate, he arranged for a variety of responses throughout the Land of Make Believe. One puppet, Lady Elaine, is eager to act out what she has seen: “That man got shot by that other man at least six times!”

Her neighbor, X the Owl, doesn’t want any part of what is to him a frightening-sounding game.

And Daniel, who Rogers’ wife Joanne intimated was a reflection “the real Fred,” preferred to put the topic on ice for future discussions—a luxury that the grown up Rogers would not allow himself.

The episode has become notorious, in part because it aired but once on the small screen. (The 8‑minute clip at the top of the page is the longest segment we were able to truffle up online.)

Writer and gameshow historian Adam Nedeff watched it in its entirety at the Paley Center for Media, and the detailed impressions he shared with the Neighborhood Archive website provides a sense of the piece as a whole.

Meanwhile, the Paley Center’s catalogue credits speak to the drama-in-real-life immediacy of the turnaround from conception to airdate:

Above is some of the footage Rogers feared unsuspecting children would be left to process solo. Readers, are there any among you who remember discussing this event with your parents… or children?

Ever vigilant, Rogers returned in the days immediately following the 2001 attack on the World Trade Center, with a special message for parents who had grown up watching him.

Related Content:

Mr. Rogers’ Nine Rules for Speaking to Children (1977)

All 886 episodes of Mister Roger’s Neighborhood Streaming Online (for a Limited Time)

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inkyzine. Join her in NYC on Monday, September 9 for another season of her book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...3 Iconic Paintings by Frida Kahlo Get Reborn as Vans Skate Shoes

Attention Frida Kahlo tchotchke hounds.

You can scratch that itch, even if your summer itinerary doesn’t include Mexico City (or Nashville, Tennessee, where the Frist Museum is hosting Frida Kahlo, Diego Rivera, and Mexican Modernism from the Jacques and Natasha Gelman Collection through September 2).

Taking its cue from Doc Marten’s Museum Collection, Vans is releasing three shoes inspired by some of the painter’s most iconic works, 1939’s The Two Fridas, 1940’s Self-Portrait with Thorn Necklace and Hummingbird, and—for those who prefer a more subtly Frida-inspired shoe, 1954’s refreshingly fruity Viva la Vida.

Vans’ limited edition Frida Kahlo collection hits the shelves June 29. Expect it to be snapped up quickly by the Waffleheads, Vans’ dedicated group of collectors and customizers, so don’t delay.

If this line doesn’t tickle your fancy, there is of course an abundance of Frida Kahlo tribute footwear on Etsy, everything from huaraches and Converse All-Stars to socks and baby booties.

Related Content:

A Brief Animated Introduction to the Life and Work of Frida Kahlo

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Deliberate Practice: A Mindful & Methodical Way to Master Any Skill

Each and every day we eat, we sleep, we read, we brush our teeth. So why haven’t we all become world-class masters of eating, sleeping, reading, and teeth-brushing? Most of us, if we’re honest with ourselves, plateaued on those particular skills decades ago, despite never having missed our daily practice sessions. This should tell us something important about the difference between practicing an action and simply doing it a lot, a distinction at the heart of the concept of “deliberate practice.” As the Sprouts video above explains it, deliberate practice “is a mindful and highly structured form of learning by doing,” a “process of continued experimentation to first achieve mastery and eventually full automaticity of a specific skill.”

Psychologist Anders Ericsson, the single figure most closely associated with deliberate practice, draws a distinction with what he calls naive practice: “Naive practice is people who just play games,” and in so doing “just accumulate more experience.” But in deliberate practice, “you actually pinpoint something you want to change. And once you have that specific goal of changing it, you will now engage in a practice activity that has a purpose of changing that.”

As a post on deliberate practice at Farnam Street puts it, “great performers deconstruct elements of what they do into chunks they can practice. They get better at that aspect and move on to the next,” often under the guidance of a teacher who can more clearly see their strengths and weaknesses in action.

“Most of the time we’re practicing we’re really doing activities in our comfort zone,” says the Farnam Street post. “This doesn’t help us improve because we can already do these activities easily” — just as easily, perhaps, as we eat, sleep, read, and brush our teeth. But we also fail to improve when we operate at the other end of the spectrum, in the “panic zone” that “leaves us paralyzed as the activities are too difficult and we don’t know where to start. The only way to make progress is to operate in the learning zone, which are those activities that are just out of reach.” As in every other area of life, what challenges us too much frustrates us and what challenges us too little bores us; only at just the right balance do we benefit.

But striking that balance presents challenges of its own, challenges that have ensured a readership for writings on the subject of how best to engage in deliberate practice by Ericsson as well as many others (such as writer-entrepreneur James Clear, whose beginner’s guide to deliberate practice you can read online here). The video above on Ericsson’s book Peak: How to Master Almost Anything explains his view of the goal of deliberate practice as to develop the kind of library of “mental representations” that masters of every discipline — golfers, doctors, guitarists, comedians, novelists — use to approach every situation that might arise. Developing those mental representations requires specific goals, intense periods of practice, immediate feedback during that practice, and above all, frequent discomfort. Everyone enjoys mastery once they attain it, but if you find yourself having too much fun on the way, consider the possibility that you’re not practicing deliberately enough.

Related Content:

What’s a Scientifically-Proven Way to Improve Your Ability to Learn? Get Out and Exercise

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall, on Facebook, or on Instagram.

Read More...