Hear the Trippy Mystical Sounds of Giant Gongs

Growing up I thought there were only two uses for gongs. One was for making one large bonnnnnnng sound for something important, like the announcement of a royal banquet or the beginning of a J. Arthur Rank production. The other was as a weapon against cartoon animals–it would make a funny sound and their heads would be turned into a pancake. How was I to know there was so much more to gongs, especially 80-inch wide gongs that cost around $27,000? Thank goodness for YouTube, then.

The above video features Sven aka Gong Master Sven aka Paiste Gong Master Sven (it’s not very clear in the description) very gingerly playing this monster symphonic gong, coaxing out of it menacing, echoing groans and wails straight out of a horror movie.

Just a gentle stroke can cause the metal to vibrate and feed back onto itself. Using a smaller mallet produces sounds like whale songs. That something so large can make such a stunning array of tones, and react to such delicacy is fascinating. (Watch with headphones on or a good sound system, by the way).

If that whets your whistle, here’s more gong action with musician Bear Love, who manages to make his gong sound like something out of science fiction, incredibly creepy. If there’s a ghost story movie out there with a one-gong soundtrack, I’d believe it.

Michael Bettine plays the same Paiste gong in a more familiar way, by whacking it with a big mallet. It’s impressive, and he doesn’t really hit it that hard. “You can feel your internal organs being massaged by the vibrations,” he says.

Finally, Tom Soltron Czartoryski, slims it down to a 62 inch “earth gong” with its array of indentations, and creates a nearly 10 minute ambient work, which is one expansive dose of space music. Groovy and sometimes stressful, fascinating and all-encompassing. Enjoy!

(Note to self: Resolve to find a local giant gong and have a go.)

via Kottke.org

Related Content:

A Modern Drummer Plays a Rock Gong, a Percussion Instrument from Prehistoric Times

Hear a 9,000 Year Old Flute—the World’s Oldest Playable Instrument—Get Played Again

Punk Dulcimer: The Ramones’ “I Wanna Be Sedated” Played on the Dulcimer

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Read More...Neil deGrasse Tyson Teaches Scientific Thinking and Communication in a New Online Course

One doesn’t normally get into astrophysics for the fame. But sometimes one gets famous anyway, as has astrophysicist Neil DeGrasse Tyson, Director of the Hayden Planetarium at the Rose Center for Earth and Space. But that title doesn’t even hint at the scope of his public-facing ventures, from the columns he’s written in magazines like Natural History and StarDate to his hosting of television shows like NOVA and the sequel to Carl Sagan’s Cosmos to his podcast StarTalk and his high-profile social media presence. Has any other figure in the annals of science communication been as prolific, as outspoken, and as willing to talk to anyone and do anything?

Here on Open Culture, we’ve featured Tyson recommending books, giving a brief history of everything, delivering “the greatest science sermon ever,” chatting about NASA’s flyby of Pluto with Stephen Colbert, “performing” in a Symphony of Science video, inventing a physics-based wrestling move in high school, looking hip in grad school, defending science in 272 words, breaking down the genius of Isaac Newton, talking non-Newtonian solids with a nine-year-old, discussing the history of video games, creating a video game with Neil Gaiman and George R.R. Martin, selecting the most astounding fact about the universe, explaining the importance of arts education alongside David Byrne, pondering whether the universe has a purpose, debating whether or not we live in a simulation, remembering when first he met Carl Sagan, interviewing Stephen Hawking just days before the latter’s death, and of course, moonwalking.

Now comes Tyson’s latest media venture: a course from Masterclass, the online education company that specializes in bringing big names from various fields in front of the camera and getting them to tell us what they know. (Other teachers include Malcolm Gladwell, Steve Martin, and Werner Herzog.) “Neil DeGrasse Tyson Teaches Scientific Thinking and Communication,” whose trailer you can watch above, gets into subjects like the scientific method, the nature of skepticism, cognitive and cultural bias, communication tactics, and the inspiration of curiosity. “There’s, like, a gazillion hours of me on the internet,” admits Tyson, and though none of those may cost $90 USD (or $180 for an all-access pass to all of Masterclass’ offerings), in none of them has he taken on quite the goal he does in his Masterclass: to teach how to “not only find objective truth, but then communicate to others how to get there. It’s not good enough to be right. You also have to be effective.” You can sign up Tyson’s course here.

If you sign up for a MasterClass course by clicking on the affiliate links in this post, Open Culture will receive a small fee that helps support our operation.

Related Content:

Masterclass Is Running a “Buy One, Give One Free” Deal

Neil deGrasse Tyson Lists 8 (Free) Books Every Intelligent Person Should Read

Neil deGrasse Tyson Presents a Brief History of Everything in an 8.5 Minute Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...The Prado Museum Digitally Alters Four Masterpieces to Strikingly Illustrate the Impact of Climate Change

According to the United Nations’ Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change, global warming is likely to reach 1.5°C above pre-industrial levels between 2030 and 2052 should it continue to increase at its current rate.

What does this mean, exactly?

A catastrophic series of chain reactions, including but not limited to:

–Sea level rise

–Change in land and ocean ecosystems

–Increased intensity and frequency of weather extremes

–Temperature extremes on land

–Drought due to precipitation deficits

–Species loss and extinction

Look to the IPCC’s 2018 Special Report: Global Warming of 1.5°C for more specifics, or have a gander at these digital updates of masterpieces in Madrid’s Museo del Prado’s collections.

The museum collaborated with the World Wildlife Fund, choosing four paintings to be altered in time for the recently wrapped Madrid Climate Change Conference.

Artist Julio Falagan brings extreme drought to bear on El Paso de la Laguna Estigia (Charon Crossing the Styx) by Joachim Patinir, 1520 — 1524

Marta Zafra raises the sea level on Felipe IV a Caballo (Philip the IV on Horseback) by Velázquez, circa 1635.

The Parasol that supplies the title for Francisco de Goya’s El Quitasol of 1777 becomes a tattered umbrella barely sheltering miserable, crowded refugees in the sodden, makeshift camp of Pedro Veloso’s reimagining.

And the Niños en la Playa captured relaxing on the beach in 1909 by Joaquín Sorolla now compete for space with dead fish, as observed by artist Conspiracy 110 years further along.

None of the original works are currently on display.

It would be a public service if they were, alongside their drastically retouched twins and perhaps Hieronymus Bosch’s The Garden of Earthly Delights, to further unnerve viewers about the sort of hell we’ll soon be facing if we, too, don’t make some major alterations.

For now the works in the +1.5ºC Lo Cambia Todo (+1.5ºC Changes Everything) project are making an impact on giant billboards in Madrid, as well as online.

Related Content:

Global Warming: A Free Course from UChicago Explains Climate Change

Climate Change Gets Strikingly Visualized by a Scottish Art Installation

A Century of Global Warming Visualized in a 35 Second Video

Perpetual Ocean: A Van Gogh-Like Visualization of our Ocean Currents

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, January 6 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domaincelebrates Cape-Coddities by Roger Livingston Scaife (1920). Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Neil Gaiman Talks Dreamily About Fountain Pens, Notebooks & His Writing Process in His Long Interview with Tim Ferriss

Last February, Neil Gaiman sat down for a 90-minute interview with author, entrepreneur and podcaster Tim Ferriss. At the 13:30 mark, the conversation turns to Gaiman’s writing process, and there begins a long and lovely detour into the world of fountain pens (the Pilot 823, Viscontis, and the New York Fountain Pen Hospital in NYC), notebooks (why he prefers Leuchtturm German notebooks to Moleskines), and how he writes his novels out by hand. It’s all carefully thought out:

Tim Ferriss: Are there any other rules or practices that you also hold sacred or important for your writing process?

Neil Gaiman: Some of them are just things for me. For example, most of the time, not always, I will do my first draft in fountain pen, because I actually enjoy the process of writing with a fountain pen. I like the feeling of fountain pen. I like uncapping it. I like the weight of it in my hand. I like that thing, so I’ll have a notebook, I’ll have a fountain pen, and I’ll write. If I’m doing anything long, if I’m working on a novel, for example, I will always have two fountain pens on the go, at least, with two different colored inks, at least, because that way I can see at a glance, how much work I did that day. I can just look down and go, “Look at that! Five pages in brown. How about that? Half a page in black. That was not a good day. Nine pages in blue, cool, what a great day.”

You can just get a sense of are you working, are you making forward progress? What’s actually happening. I also love that because it emphasizes for me that nobody is ever meant to read your first draft. Your first draft can go way off the rails, your first draft can absolutely go up in flames, it can — you can change the age, gender, number of a character, you can bring somebody dead back to life. Nobody ever needs to know anything that happens in your first draft. It is you telling the story to yourself.

Then, I’ll sit down and type. I’ll put it onto a computer, and as far as I’m concerned, the second draft is where I try and make it look like I knew what I was doing all along.

Tim Ferriss: Do you edit, then, as you’re looking or translating from the first draft on the page to the computer, or do you get it all down as is in the computer and then edit —

Neil Gaiman: No, that’s my editing process. I figure that’s my second draft is typing into the computer. Also, I love — backing up a bit here. When I was, what was I? 27, 28? In the days when we were still in typewriters and we were just a handful of people with word processors, which were clunky things with disks which didn’t hold very much and stuff, I edited an anthology and enjoyed editing my anthology.

Most of the stories that came in were about 3,000 words long. Move forward in time, not much, five, six, seven years. Mid ‘90s, everybody is now on computer, and I edited another short story anthology. The stories that were coming in tended to be somewhere between six- and 9,000 words long. They didn’t really have much more story than the 3,000 word ones, and I realized that what was happening is it’s a computer‑y thing, is if you’re typing, putting stuff down is work. If you’ve got a computer, adding stuff is not work. Choosing is work. It expands a bit, like a gas. If you have two things you could say, you say both of them. If you have the stuff you want to add, you add it, and I thought, “Okay, I have to not do that, because otherwise my stuff is going to balloon and it will become gaseous and thin.”

What I love, if I’ve written something on a computer, and I decide to lose a chunk, it feels like I’ve lost work. I delete a page and a half, I feel like there’s a page and half that just went away. That was a page and a half’s worth of work I’ve just lost. If I’ve been writing in a notebook and I’m typing it up, I can look at something and go, “Oh, I don’t need this page and a half.” I leave it out, I just saved myself work, and it feels like I’m treating myself.

I’m just trying to always have in my head the idea that maybe I’m somehow, on some cosmic level, paying somebody by the word in order to be allowed to write, but if they’re there, they should matter, they should mean something. It’s always important to me.

Tim Ferriss: You mentioned distraction earlier and your dangerously adorable son, which I certainly agree with. I had read somewhere, actually, before I get to that, this might seem like a very, very mundane question, but what type of notebooks do you prefer? Are they large legal pads or are they leather bound? What type of notebooks?

Neil Gaiman: When they came out, I really liked — I’ve used a whole bunch of different ones. I bought big drawing ones, which actually turned out to be a bit too big, though I liked how much I could see on the page. Those are the ones I wrote Stardust and American Gods in, big size, but they weren’t terribly portable. I went over to the Moleskines, and I loved them when they first came out, and then they dropped their paper quality. Dropping paper quality doesn’t matter, unless you’re writing in fountain pen, because all of a sudden it’s bleeding through, and all of a sudden you’re writing on one page, leaving a page blank because it’s bled through and then writing on the next page.

Joe Hill, about six or seven years ago, Joe Hill, the wonderful horror fantasy writer, suggested the Leuchtturm to me. My usual notebook right now is a Leuchtturm, because I really like the way you can paginate stuff in them and the thickness of the paper, and they’re just like Moleskines, but the Porsche of Moleskines. They’re just better.

I also have been writing, I wrote The Graveyard Book and I’m writing the current novel in these beautiful books that I bought in a stationery shop in Venice, built into a bridge. Somewhere in Venice there’s a little stationery shop on a bridge, and they have these beautiful leather-bound blank books that just look like hardback books, but they’re blank pages. I wrote The Graveyard Book in one of those. I bought four of them, and now I’m using the next one on the next novel, and it may well go into another one. I’m not sure.

Then, at home, I say at home, my house in Wisconsin, which is where my stuff is, I’ve got my — we live in Woodstock, but I have an entire life’s worth of stuff still sitting in my house in Wisconsin, and it’s become archives. It’s actually kind of fabulous having a house that is an archive, but waiting for me in that house is a book that I bought for myself about 25 years ago, and before I die, I plan to write a novel in it. It’s an accounts book from the mid-19th century. It’s 500 pages long. Every page is numbered. It’s lined with accounts lines, but really faint so it would be nice to write a book in it, and it is engineered so that every single page lies flat.

It’s huge and it’s heavy and it just looks like a book that Dickens or somebody would’ve written a novel in and I’ve just been waiting until I have an idea that is huge and weird and Dickensian enough, and whether or not I actually get to write it in dip pen, I’m not sure, but I definitely want to write it in an old Victorian, something slightly copper plating. One of those old flex nib pens that they stopped making when carbon paper came in, just so I can get that spidery Victorian handwriting.

Tim Ferriss: I’m just imagining you putting pen to the first page. When you finish the first page and what that will feel like. That’s going to be a good day.

Neil Gaiman: It will be either a good day or an incredibly bad day. When you get to the end of the first page, it’s “Oh no! I had this pristine — ” it is the thing that I tell young writers, and by young writers, a young writer can be any age. You just have to be starting out, which is anything you do can be fixed. What you cannot fix is the perfection of a blank page. What you cannot fix is that pristine, unsullied whiteness of a screen or a page with nothing on it, because there’s nothing there to fix.

Tim Ferriss: You mentioned a word, and it might be that I’m a little slow moving because I’m from Long Island, but Leuchtturm? What is that word?

Neil Gaiman: L‑E-I-C‑H, I think it’s T‑U-R‑M, and then 1917, I think is — their Twitter handle is definitely Leuchtturm1917.

Tim Ferriss: Leuchtturm, and I’ll put that in the show notes for folks, so you’ll be able to find it. Since you gave me — I’m not intending to turn this episode into a shopping list, but I’ve never used fountain pens.

Neil Gaiman: Really?

Tim Ferriss: I have not. My assistant, my dear assistant does. She loves using fountain pens. She enjoys the act. I’ve had a few sloppy false starts and then been rather impatient, but if I wanted to give it a shot, are there any particular fountain pens or criteria that you would use in picking a good pen?

Neil Gaiman: The biggest criteria I would use in picking, if you have the choice, is go somewhere like New York’s Fountain Pen Hospital.

Tim Ferriss: Is that a real place?

Neil Gaiman: It’s a real place. It’s called The Fountain Pen Hospital. They sell lots of new pens, they recondition old pens, they look after pens for you. And try them out, because the lovely thing about fountain pens is they are personal. You go, “No, no, no.” And then you find the one. I tend to suggest to people who are just nervously — “I’ve never used a fountain pen, what should I do?” I will point them at Lamy, L‑A-M‑Y, who have some fabulous starter pens, and they’re not very expensive, and they’re good. They do a pen called The Safari, but they have a bunch of good starter pens, and they’re just nice to get into the idea of, “Do I like doing this?”

Let’s see, what am I using right now? What have I got in here? This one here is a Pilot. It’s a Namiki, and it’s a flexing nib ever so slightly when you put down weight on it, the nib will spread. It’s a beautiful, beautiful pen. That one’s a Pilot. I think this one here is the Namiki. It’s really weird because Namiki is Pilot, so I don’t quite understand that.

Tim Ferriss: Maybe it’s a Toyota/Lexus thing?

Neil Gaiman: I think it is. It’s that kinda thing. This one here is called a Falcon, and again, you put a little bit of weight on it, and the line will just spread and thicken, which is part of the fun of fountain pens. I’ll go and play. There’s a lovely Italian one. I’ve got my agent, I did a thing some years ago when I realized that I was losing a lot of actual writing time to signing foreign contracts.

Tim Ferriss: This is for books?

Neil Gaiman: This is for books, or occasionally for stories or things being reprinted around the world. The contracts would come in and there would be big sheaves of them because they get printed all around the world, and foreign contracts, a lot of them you have to sign a lot. You have to do a lot of initialing and I would sit there going, “I have just spent 90 minutes signing a pile of contracts, and I love that I got to sign it, but —” I contacted my agent. I said, “Can I give you power of attorney? Would you mind? Would you just sign these things for me?”

She was like, “Absolutely!” Great. I got her — she’d never used a fountain pen and I got her a fountain pen. I actually went to The New York Fountain Pen Hospital with her, and did the thing of showing her pens, “What do you like?” I got her a Visconti, which are just these lovely Italian pens. Mostly I love, there’s a slightly fetishistic bit of having bottles of beautifully colored ink. When you start talking to fountain pen people, they really — they pretend to be interested in what pen you like, but they don’t care, because they’ve found their own pens that they love.

They say, “What do you use?”

I use Pilot 823s for signing. Actually now, I’ve got a Pilot 823, ’cause it’s just a fantastic signing pen. It’s a workhorse, it keeps going, and I got one in 2012 and it was my signing pen. I signed through Ocean at the End of the Lane. Before the book had come out, I had already pre-signed, written my signature 20,000 times with this pen.

Tim Ferriss: I have some footage of you icing your hand after said signings.

Neil Gaiman: That was a signing tour that I really got into icing my hand and wrist and arm. I did the numbers, and as far as I can tell, I’ve signed about one and a half million signatures with that pen, which remained, and I had to send it off to Pilot at one point, not because the nib was in trouble, because the plunger mechanism was starting to stick, and they fixed it for me and sent it back. Then my three-year-old son found a place behind a cast iron fireplace in our house in Woodstock where if you just insert your father’s Pilot 823 pen, which you have found on the table, just to see if it would go in there, you can actually guarantee that without disassembling the house, we actually have to take the entire house apart to uninstall a cast iron fireplace from 1913 to get at the pen. That pen now has been given as a sacrifice to the house gods, so I need to get a new one.

Tim Ferriss: Its strikes me, at least it seems as we’re talking that many of the decisions you’ve made, the tools you’ve found and enlisted, act to make not writing unappealing, or at least boring after five minutes, and to enhance the act of writing to make it something that is enjoyable. I don’t know if that’s true.

Neil Gaiman: That is true, but they also exist for another reason, which is kind of weird, which is to try and trivialize what I’m doing and not make it important and freighted down with weight, because that paralyzes me. When I started writing I had a typewriter. It was a manual typewriter. When I sold my first book, I had the money to buy an electric typewriter.

Tim Ferriss: What was that first book?

Neil Gaiman: Gosh. I actually don’t remember whether I bought the electric typewriter with the money from a book called Ghastly Beyond Belief, a book of science fiction and fantasy quotations I did with Kim Newman, or whether it was for the Duran Duran biography that I did. Either way, I was just 23. What I would do back then is I would do my rough draft on scrap paper, single spaced so that it couldn’t be used, and also so that I could get as many words on. Paper was expensive. I could always do that. I remember the joy of getting my first computer, and just the idea that I wasn’t making paper dirty. Nothing mattered until I pressed print, and that was absolutely and utterly liberating.

And then, a decade on, picking up a notebook, it was for Stardust, which I’d decided that I wanted the rhythms of Stardust to be very antiquated rhythms, and I thought there’s probably a difference to the way that one writes with a fountain pen. 17 century writing, 17th, 18th century writing, you notice tends to go in very, very long sentences and long paragraphs. My theory about this is that one reason why you get this is because you’’re using dip pens, and if you pause, they dry up. You just have to keep going. It forces you to do a kind of writing where you’re going for a very long sentence and you’re going to go for a long paragraph and you’re going to keep moving in this thing, and you’re thinking ahead.

If you’re writing on a computer, you’ll think of the sort of thing that you mean, and then write that down and look at it and then fiddle with it and get it to be the thing that you mean. If you’re writing in fountain pen, if you do that, you just wind up with a page covered with crossings out, so it’s actually so much easier to just think a little bit more. You slow up a bit, but you’re thinking the sentence through to the end, and then you start writing.

You write that, and then you pause and then you write the next one. At least that was the way that I hypothesized that I might be writing, and I wanted Stardust to feel like it had been written in the late 1920s. I thought to do that I should probably get myself a fountain pen and a book, so that was how I started writing that. Again, what I loved was suddenly feeling liberated. Saying, “Ah, I’m not actually making words that are not going down in phosphor on a computer screen.”

Watch the full interview above. Stream it as a podcast. Or read the complete transcript here.

Related Content:

18 Stories & Novels by Neil Gaiman Online: Free Texts & Readings by Neil Himself

Where Do Great Ideas Come From? Neil Gaiman Explains

Neil Gaiman Teaches the Art of Storytelling in His New Online Course

Amanda Palmer Animates & Narrates Husband Neil Gaiman’s Unconscious Musings

Read More...Plants Emit High-Pitched Sounds When They Get Cut, or Stressed by Drought, a New Study Shows

Image via Wikimedia Commons

Are plants sentient? We know they sense their environments to a significant degree; like animals, they can “see” light, as a New Scientist feature explains. They “live in a very tactile world,” have a sense of smell, respond to sound, and use taste to “sense danger and drought and even to recognize relatives.” We’ve previously highlighted research here on how trees talk to each other with chemical signals and form social bonds and families. The idea sets the imagination running and might even cause a little paranoia. What are they saying? Are they talking about us?

Maybe we deserve to feel a little uneasy around plant life, given how ruthlessly our consumer economies exploit the natural world. Now imagine we could hear the sounds plants make when they’re stressed out. In addition to releasing volatile chemicals and showing “altered phenotypes, including changes in color, smell, and shape,” write the authors of a new study published at bioRxiv, it’s possible that plants “emit airborne sounds [their emphasis] when stressed—similarly to many animals.”

The researchers who tested this hypothesis at Tel Aviv University “found that tomato and tobacco plants made sounds at frequencies humans cannot hear,” New Scientist reports. “Microphones placed 10 centimetres from the plants picked up sounds in the ultrasonic range of 20 to 100 kilohertz, which the team say insects and some mammals would be capable of hearing and responding to from as far as 5 metres away.”

The plants made these sounds when stressed by lack of water or when their stems were cut. Tomato plants stressed by drought made an average of 35 sounds per hour. Tobacco plants, on average, made 11. Unstressed plants, by contrast, “produced fewer than one sound per hour.” The scientists used machine learning to distinguish between different kinds of distress calls, as it were, and different kinds of plants, “correctly identifying in most cases whether the stress was caused by dryness or a cut,” and they conducted the experiments in both closed acoustic chambers and a greenhouse.

Plants do not, of course, have vocal cords or auditory systems. But they do experience a process known as “cavitation,” in which “air bubbles form, expand and explode in the xylem, causing vibrations,” the paper explains. These vibrations have been recorded in the past by direct, contact-based methods. This new study, which has yet to pass peer review, might be the first to show how plants might use sound to communicate with each other and with other living organisms, suggesting “a new modality of signaling.”

The possibilities for future research are fascinating. We might learn, for example, that “if plants emit sounds in response to a caterpillar attack, predators such as bats could use these sounds to detect attacked plants and prey on the herbivores, thus assisting the plant.” And just as trees are able to respond to each other’s distress when they’re connected in a forest, “plants could potentially hear their drought stressed or injured neighbors and react accordingly”—however that might be.

Much remains to be learned about the sensory lives of plants. Whether their active calls and responses to the stimuli around them are indicative of a kind of consciousness seems like a philosophical as much as a biological question. But “even if the emission of the sounds is entirely involuntary,” the researchers write (seeming to leave room for plant volition), it’s a phenomenon that counts as a form of communication: maybe even what we might someday call plant language, different from species to species and, perhaps, between individual plants themselves.

Related Content:

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...Watch a Hand-Drawn Animation of Neil Gaiman’s Poem “The Mushroom Hunters,” Narrated by Amanda Palmer

The arrival of a newborn son has inspired no few poets to compose works preserving the occasion. When Neil Gaiman wrote such a poem, he used its words to pay tribute to not just the creation of new life but to the scientific method as well. “Science, as you know, my little one, is the study / of the nature and behavior of the universe,” begins Gaiman’s “The Mushroom Hunters.” An important thing for a child to know, certainly, but Gaiman doesn’t hesitate to get into even more detail: “It’s based on observation, on experiment, and measurement / and the formulation of laws to describe the facts revealed.” Go slightly over the head of a newborn as all this may, any parent of an older but still young child knows what question naturally comes next: “Why?”

As if in anticipation of that inevitable expression of curiosity, Gaiman harks back to “the old times,” when “men came already fitted with brains / designed to follow flesh-beasts at a run,” and with any luck to come back with a slain antelope for dinner. The women, “who did not need to run down prey / had brains that spotted landmarks and made paths between them,” taking special note of the spots where they could find mushrooms. It was these mushroom hunters who used “the first tool of all,” a sling to hold the baby but also to “put the berries and the mushrooms in / the roots and the good leaves, the seeds and the crawlers. / Then a flint pestle to smash, to crush, to grind or break.” But how to know which of the mushrooms — to say nothing of the berries, roots, and leaves — will kill you, which will “show you gods,” and which will “feed the hunger in our bellies?”

“Observe everything.” That’s what Gaiman’s poem recommends, and what it memorializes these mushroom hunters for having done: observing the conditions under which mushrooms aren’t deadly to eat, observing childbirth to “discover how to bring babies safely into the world,” observing everything around them in order to create “the tools we make to build our lives / our clothes, our food, our path home…” In Gaiman’s poetic view, the observations and formulations made by these early mushroom-hunting women to serve only the imperative of survival lead straight (if over a long distance), to the modern scientific enterprise, with its continued gathering of facts, as well as its constant proposal and revision of laws to describe the patterns in those facts.

You can see “The Mushroom Hunters” brought to life in the video above, a hand-drawn animation by Creative Connection scored by the composer Jherek Bischoff (previously heard in the David Bowie tribute Strung Out in Heaven). You can read the poem at Brain Pickings, whose creator Maria Popova hosts “The Universe in Verse,” an annual “charitable celebration of science through poetry” where “The Mushroom Hunters” made its debut in 2017. There it was read aloud by the musician Amanda Palmer, Gaiman’s wife and the mother of the aforementioned son, and so it is in this more recent animated video. Young Ash will surely grow up faced with few obstacles to the appreciation of science, and even less so to the kind of imagination that science requires. As for all the other children in the world — well, it certainly wouldn’t hurt to show them the mushroom hunters at work.

This reading will be added to our collection, 1,000 Free Audio Books: Download Great Books for Free.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

Watch Neil Gaiman & Amanda Palmer’s Haunting, Animated Take on Leonard Cohen’s “Democracy”

Amanda Palmer Animates & Narrates Husband Neil Gaiman’s Unconscious Musings

Watch Lovebirds Amanda Palmer and Neil Gaiman Sing “Makin’ Whoopee!” Live

Neil Gaiman’s Dark Christmas Poem Animated

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities and culture. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer, the video series The City in Cinema, and the crowdfunded journalism project Where Is the City of the Future? Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...You Can Sleep in an Edward Hopper Painting at the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts: Is This the Next New Museum Trend?

Let’s pretend our Fairy Art Mother is granting one wish—to spend the night inside the painting of your choice.

What painting will we each choose, and why?

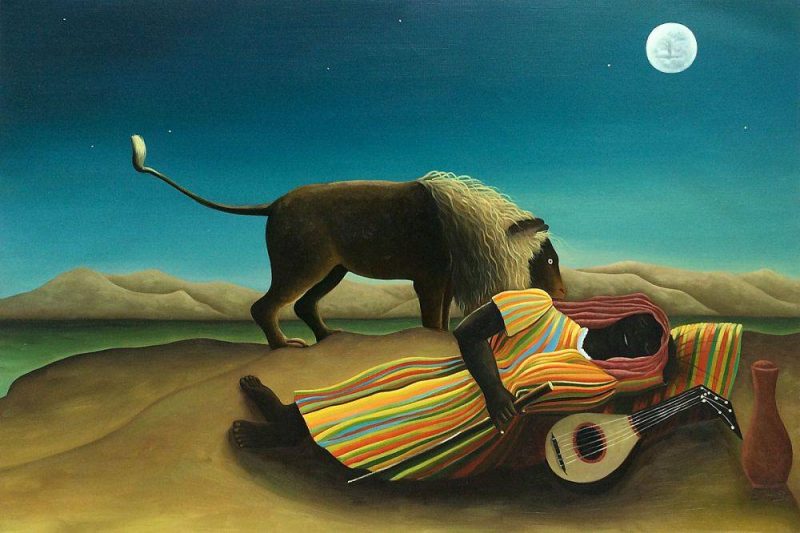

Will you sleep out in the open, undisturbed by lions, a la Rousseau’s The Sleeping Gypsy?

Or experience the voluptuous dreams of Frederic Leighton’s Flaming June?

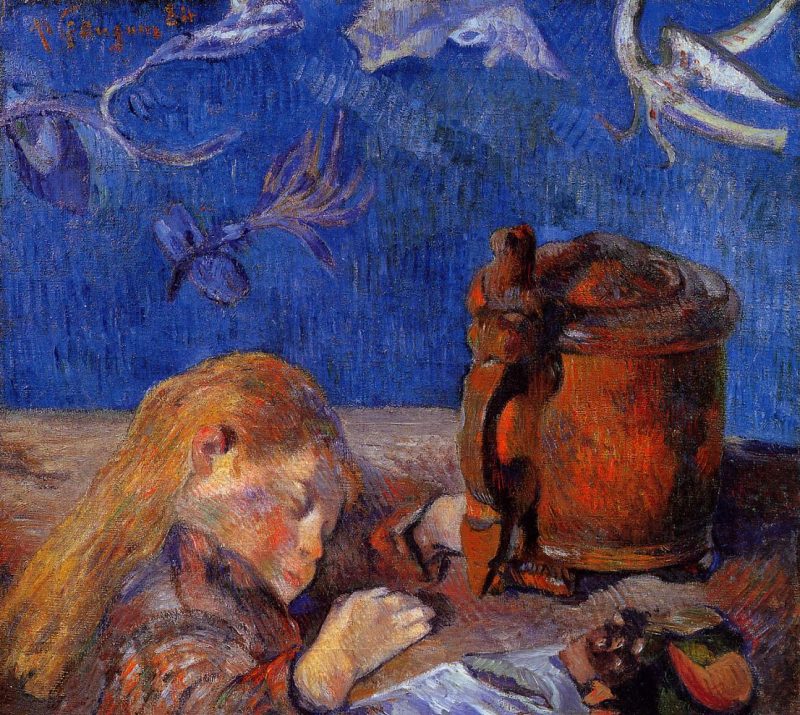

Paul Gauguin’s portrait of his son, Clovis presents a tantalizing prospect for those of us who haven’t slept like a baby in decades…

The Nightmare by Herny Fuseli should chime with Gothic sensibilities…

And it’s a fairly safe bet that some of us will select Edward Hopper’s Western Motel, at the top of this post, if only because we heard the Virginia Museum of Fine Arts was accepting double occupancy bookings for an extremely faithful facsimile, as part of its Edward Hopper and the American Hotel exhibition.

Alas, if unsurprisingly, the Hopper Hotel Experience, with mini golf and a curated tour, sold out quickly, with prices ranging from $150 to $500 for an off-hours stay.

Ticket-holding visitors can still peer in at the room any time the exhibit is open to the public, but it’s after hours when the Instagramming kicks into high gear.

What guest could resist the temptation to strike a pose amid the vintage luggage and (bluetooth-enabled) wood paneled radio, filling in for the 1957 painting’s lone figure, an iconic Hopper woman in a burgundy dress?

The Art Institute of Chicago notes that she is singular among Hopper’s subjects, in that she appears to be gazing directly at the viewer.

But as per the Yale University Art Gallery, from which Western Motel is on loan:

The woman staring across the room does not seem to see us; the pensiveness of her stare and her tense posture accentuate the sense of some impending event. She appears to be waiting: the luggage is packed, the room is devoid of personal objects, the bed is made, and a car is parked outside the window.

Hopefully, those lucky enough to have secured a booking will have perfected the pose in the mirror at home prior to arrival. This “motel” is a bit of a stage set, in that guests must leave the painting to access the public bathroom that constitutes the facilities.

(No word on whether the theme extends to a paper “sanitized for your protection” band across the toilet, but there’s no shower and a security officer is stationed outside the room for the duration of each stay.)

The popularity of this once-in-a-lifetime exhibit tie-in may spark other museums to follow suit.

The Art Institute of Chicago started the trend in 2016 with a painstaking recreation of Vincent Van Gogh’s room at Arles, which it listed on Air BnB for $10/night.

Think of all the fun we could have if the bedrooms of art history opened to us…

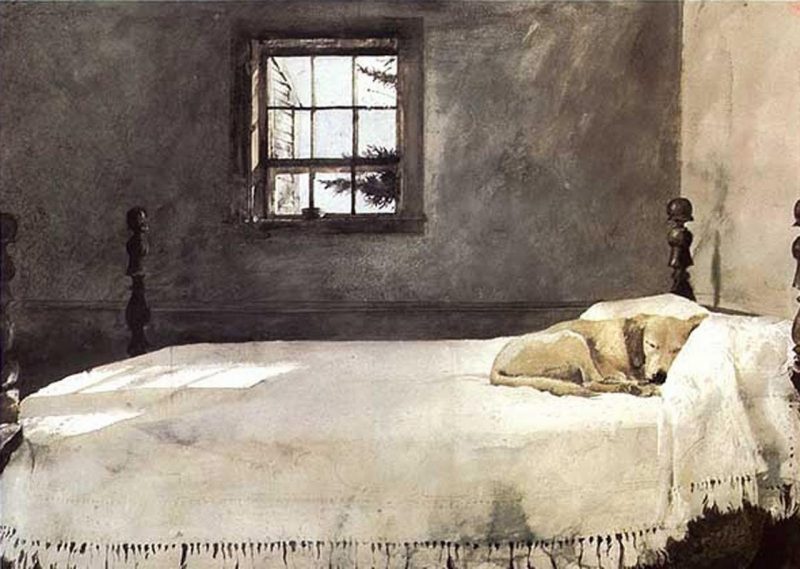

Dog lovers could get cozy in Andrew Wyeth’s Master Bedroom.

Delacroix’s The Death of Sardanapalus (1827) would require something more than double occupancy for proper Instagramming.

Piero della Francesca’s The Dream of Constantine might elicit impressive messages from the sub-conscience…

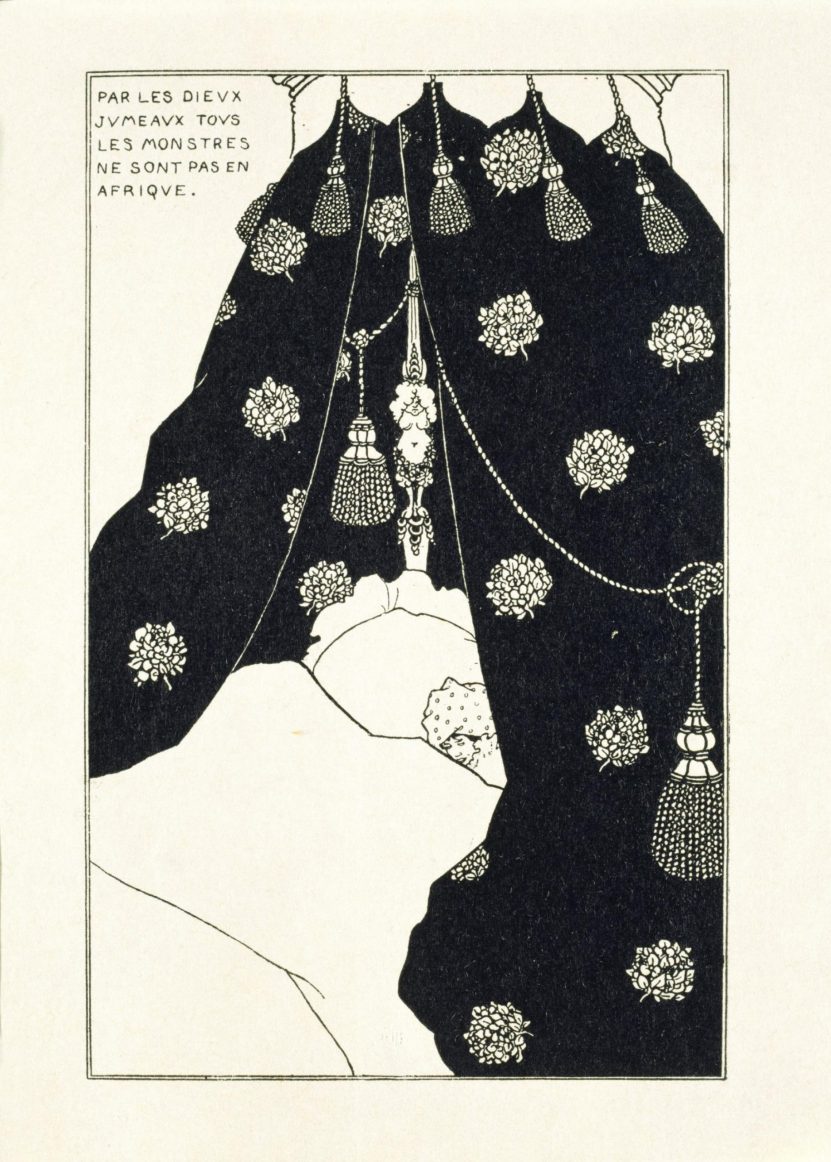

Tuberculosis nothwithstanding, Aubrey Beardsley’s Self Portrait in Bed is rife with possibilities.

Or skip the cultural foreplay and head straight for the NSFW pleasures of The French Bed, a la Rembrandt’s etching.

Edward Hopper and the American Hotel will be traveling to the Indianapolis Museum of Art at Newfields in June 2020.

Related Content:

Take a Journey Inside Vincent Van Gogh’s Paintings with a New Digital Exhibition

How Edward Hopper “Storyboarded” His Iconic Painting Nighthawks

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, December 9 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates Dennison’s Christmas Book (1921). Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...The Seven Road-Tested Habits of Effective Artists

Fifteen years ago, a young construction worker named Andrew Price went in search of free 3d software to help him achieve his goal of rendering a 3D car.

He stumbled onto Blender, a just-the-ticket open source software that helps users with every aspect of 3D creation—modeling, rigging, animation, simulation, rendering, compositing, and motion tracking.

Price describes his early learning style as “playing it by ear,” sampling tutorials, some of which he couldn’t be bothered to complete.

Desire for freelance gigs led him to forge a new identity, that of a Blender Guru, whose tutorials, podcasts, and articles would help other new users get the hang of the software.

But it wasn’t declaring himself an expert that ultimately improved his artistic skills. It was holding his own feet over the fire by placing a bet with his younger cousin, who stood to gain $1000 if Price failed to rack up 1,000 “likes” by posting 2D drawings to ArtStation within a 6‑month period.

(If he succeeded—which he did, 3 days before his self-imposed deadline—his cousin owed him nothing. Loss aversion proved to be a more powerful motivator than any carrot on a stick…)

In order to snag the requisite likes, Price found that he needed to revise some habits and commit to a more robust daily practice, a journey he detailed in a presentation at the 2016 Blender Conference.

Price confesses that the challenge taught him much about drawing and painting, but even more about having an effective artistic practice. His seven rules apply to any number of creative forms:

Andrew Price’s Rules for an Effective Artist Practice:

- Practice Daily

A number of prolific artists have subscribed to this belief over the years, including novelist (and mother!) JK Rowling, comedian Jerry Seinfeld, autobiographical performer Mike Birbligia, and memoirist David Sedaris.

If you feel too fried to uphold your end of the bargain, pretend to go easy on yourself with a little trick Price picked up from music producer Rick Rubin: Do the absolute minimum. You’ll likely find that performing the minimum positions you to do much more than that. Your resistance is not so much to the doing as it is to the embarking.

- Quantity over Perfectionism Masquerading as Quality

This harkens back to Rule Number One. Who are we to say which of our works will be judged worthy. Just keep putting it out there—remember it’s all practice, and law of averages favors those whose output is, like Picasso’s, prodigious. Don’t stand in the way of progress by splitting a single work’s endless hairs.

- Steal Without Ripping Off

Immerse yourself in the creative brilliance of those you admire. Then profit off your own improved efforts, a practice advocated by the likes of musician David Bowie, computer visionary Steve Jobs, and artist/social commentator Banksy.

- Educate Yourself

As a stand-alone, that old chestnut about practice making perfect is not sufficient to the task. Whether you seek out online tutorials, as Price did, enroll in a class, or designate a mentor, a conscientious commitment to study your craft will help you to better master it.

- Give yourself a break

Banging your head against the wall is not good for your brain. Price celebrates author Stephen King’s practice of giving the first draft of a new novel six weeks to marinate. Your break may be shorter. Three days may be ample to juice you up creatively. Just make sure it’s in your calendar to get back to it.

- Seek Feedback

Filmmaker Taika Waititi, rapper Kanye West, and the big gorillas at Pixar are not threatened by others’ opinions. Seek them out. You may learn something.

- Create What You Want To

Passion projects are the key to creative longevity and pleasurable process. Don’t cater to a fickle public, or the shifting sands of fashion. Pursue the sorts of things that interest you.

Implicit in Price’s seven commandments is the notion that something may have to budge—your nightly cocktails, the number of hours spent on social media, that extra half hour in bed after the alarm goes off… Don’t neglect your familial or civic obligations, but neither should you shortchange your art. Life’s too short.

Read the transcript of Andrew Price’s Blender Conference presentation here.

Related Content:

The Daily Habits of Famous Writers: Franz Kafka, Haruki Murakami, Stephen King & More

The Daily Habits of Highly Productive Philosophers: Nietzsche, Marx & Immanuel Kant

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, December 9 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates Dennison’s Christmas Book (1921). Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...The First High-Resolution Map of America’s Food Supply Chain: How It All Really Gets from Farm to Table

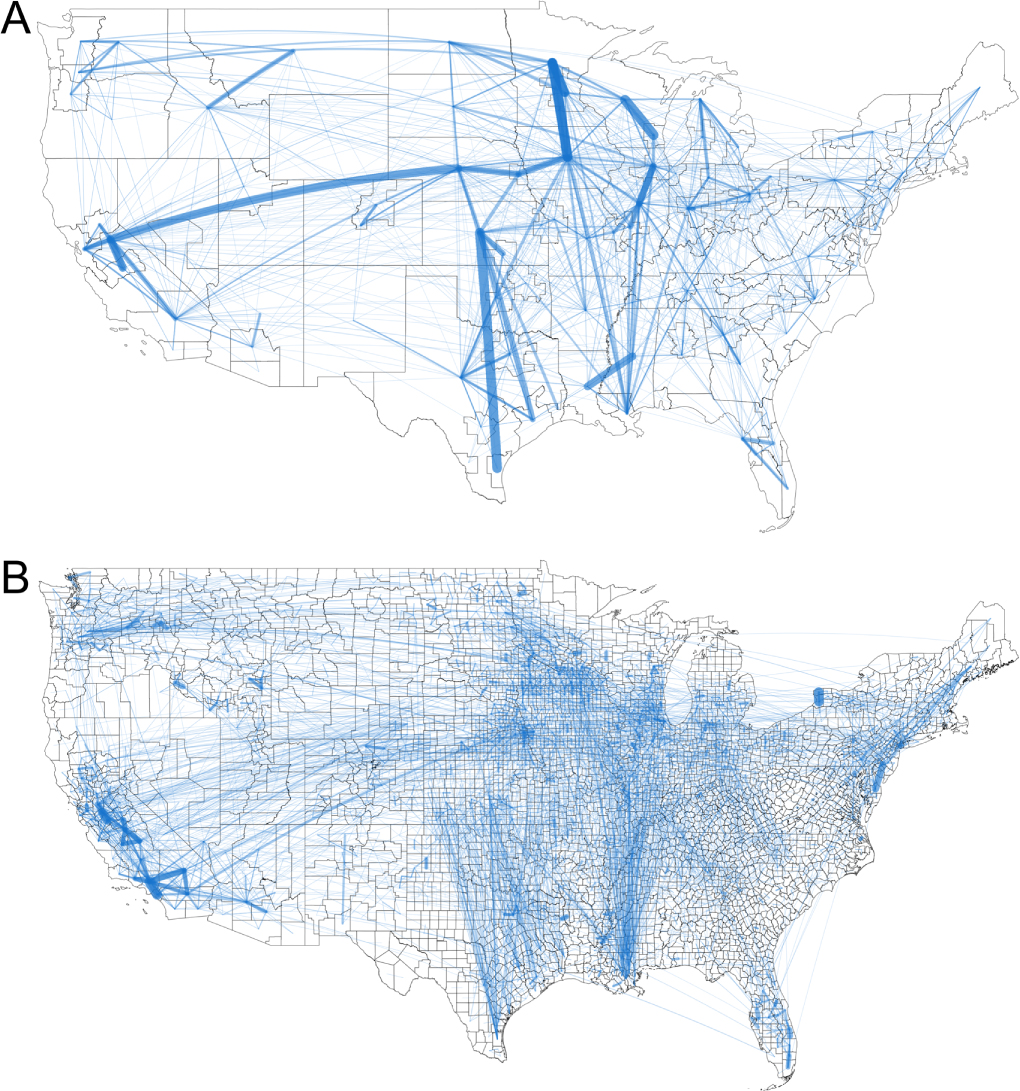

The phrase “farm to table” has enjoyed vogue status in American dining long enough to be facing displacement by an even trendier successor, “farm to fork.” These labels reflect a new awareness — or an aspiration to awareness — of where, exactly, the food Americans eat comes from. A vast and fertile land, the United States produces a great deal of its own food, but given the distance of most of its population centers from most of its agricultural centers, it also has to move nearly as great a deal of food over long domestic distances. Here we have the very first high-resolution map of that food supply chain, created by researchers at the University of Illinois studying “food flows between counties in the United States.”

“Our map is a comprehensive snapshot of all food flows between counties in the U.S. – grains, fruits and vegetables, animal feed, and processed food items,” writes Assistant Professor of Civil and Environmental Engineering Megan Konar in an explanatory post at The Conversation. (The top version shows the total tons of food moved, and the bottom one is broken down to the county scale.)

“All Americans, from urban to rural are connected through the food system. Consumers all rely on distant producers; agricultural processing plants; food storage like grain silos and grocery stores; and food transportation systems.” The map visualizes such journeys as that of a shipment of corn, which “starts at a farm in Illinois, travels to a grain elevator in Iowa before heading to a feedlot in Kansas, and then travels in animal products being sent to grocery stores in Chicago.”

Konar and her collaborators’ research arrives at a few surprising conclusions, such as that Los Angeles county is both the largest shipper and receiver of food in the U.S. Not only that, but almost all of the nine counties “most central to the overall structure of the food supply network” are in California. This may surprise anyone who has laid eyes on the sublimely huge agricultural landscapes of the Midwest “Cornbelt.” But as Konar notes, “Our estimates are for 2012, an extreme drought year in the Cornbelt. So, in another year, the network may look different.” And of the grain produced in the Midwest, much “is transported to the Port of New Orleans for export. This primarily occurs via the waterways of the Ohio and Mississippi Rivers.”

Konar also warns of troubling frailties: “The infrastructure along these waterways—such as locks 52 and 53—are critical, but have not been overhauled since their construction in 1929,” and if they were to fail, “commodity transport and supply chains would be completely disrupted.” The analytical minds at Hacker News have been discussing the implications of the research shown on this map, including whether the U.S. food supply chain is really, as one commenter put it, “very brittle and contains many weak points.” The American Society of Civil Engineers, as Konar tells Food & Wine, has given the country’s civil engineering infrastructure a grade of D+, which at least implies considerable room for improvement. But against what from some angles look like long odds, food keeps getting from American farms to American tables — and American forks, American mouths, American stomachs, and so on.

Related Content:

Download 91,000 Historic Maps from the Massive David Rumsey Map Collection

View and Download Nearly 60,000 Maps from the U.S. Geological Survey (USGS)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...How to Find Silence in a Noisy World

“Take a walk at night,” wrote avant-garde composer Pauline Oliveros in her 1974 “Sonic Meditations,” a set of instructions for what she called deep listening. “Walk so silently that the bottom of your feet become ears.” Listening to silence opens up rich new worlds of sound. It can be a life-changing experience.

“It’s hard to imagine that a sound can transform someone’s life, but it happened to me,” says acoustic ecologist Gordon Hempton in the short 360-degree documentary above, “How to Find Silence in a Noisy World.” Hempton learned to walk silently while carrying a microphone, documenting his listening journey through remote places like the Hoh Rainforest in Washington state, considered one of the quietest places in North America.

“By holding a microphone, I became a better listener. I learned that the microphone doesn’t listen for what’s important, it doesn’t judge, it doesn’t interfere.” The microphone, that is, has no ego. Recorded and amplified, the silence of the Hoh becomes cacophony, or a symphony, depending on how we describe it. Maybe any description gets in the way of listening. “Just listen,” says Hempton. “Silence is the poetics of space. What it means to be in a place… Silence isn’t the absence of something, but the presence of everything

If silence is full of sound, why might we crave it when we’re stressed? Because we are bombarded by noise pollution, “sounds that have nothing to do with the natural acoustic system.” These sounds have been encroaching on places like the Hoh Rainforest for many decades, and Hempton has documented their incursion over the past 30 years, building a collection of over 100 recordings “equipped with a 3‑D microphone system that replicates human hearing,” notes Brain Pickings.

“Emanating from his collection… is the idea that ‘there is a fundamental frequency for each habitat’—a tonal quality that shapes the sense of place and quality of presence.” Hempton’s work complements the nature recordings of Bernie Krause, former musician turned renowned expert on natural sound, whose theory of biophony describes how natural sounds work together to fill in the spectrum, each one establishing its own specific bandwidth so as not to drown out the others.

Natural sounds create a kind of self-regulating harmony. In order to fully inhabit the space we’re in, we must be able to hear them. But as the recordings made by Hempton and Krause show us, humans have a unique ability to feel ourselves deeply immersed in other places, too, by listening to recordings of their silences. Hempton implies that recordings may soon be all we have left.

“Silence,” he says, “is on the verge of extinction. There is not one place left on planet Earth that is set aside and off limits to noise pollution.” It interferes with the cycles of mating animals, disrupts call and response patterns ecosystems use to coordinate themselves. Silence is part of a global biofeedback system, telling us to quiet down, slow down, and become part of all that’s happening around us. We ignore it to our great detriment.

via Brain Pickings

Related Content:

Free: Download the Sublime Sights & Sounds of Yellowstone National Park

10 Hours of Ambient Arctic Sounds Will Help You Relax, Meditate, Study & Sleep

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...