A 5‑Hour, One-Take Cinematic Tour of Russia’s Hermitage Museum, Shot Entirely on an iPhone

In 2002, Russian filmmaker Alexander Sokurov made cinema history with Russian Ark, which dramatizes a wide swath of his homeland’s history in a single, unbroken 96-minute shot. What’s more, he and his collaborators shot it all in a single location, one both rich with historical resonance and not exactly wide-open to movie shoots: St Petersburg’s State Hermitage Museum, whose complex includes the former Winter Palace, official residence of Russia’s emperors from 1732 to until the 1917 revolution. What viewer could forget Russian Ark’s breathtaking final scene, which opens as the camera floats into the midst of a grand ball set in 1913 — taking place in the very hall it would have in 1913?

Now, at least in terms of duration, Apple has gone to the Hermitage and done Sokurov one better: its new advertisement for the iPhone 11 Pro is a five-hour journey through the entire museum, shot by filmmaker Axinya Gog in one continuous take — all, of course, on the phone itself. Like Russian Ark, it constitutes a cinematic achievement not possible before recent technological advances. Sokurov demonstrated the new possibilities of digital video camera that could capture film-like images; Gog demonstrates the new possibilities of a camera-phone with not only the battery life to shoot five straight hours of video, but at a resolution that looks at least as good as the cutting-edge digital video of 2002.

Just above appears the trailer for the ad, which hints that what the full production might lack in storytelling ambitions compared to a film like Russian Ark, it makes up for in not just duration but other human elements. Gog’s camera — or rather, iPhone — captures a Hermitage Museum without the usual crowds, striking enough in itself, but also with the addition of skilled dancers and musicians (even beyond those who recorded the video’s score). This in addition to no fewer than 588 works of art spread across 43 galleries, including paintings by Rembrandt, Raphael, Caravaggio, and Rubens. The deeper you go, the more you’ll realize that, even if you’ve spent serious time in the Hermitage yourself, you’ve never had this kind of aesthetic experience there before. It may sound excessive to say “watch to the end,” but if any five-hour video has ever merited that insistence, here it is.

via Colossal

Related Content:

The Romanovs’ Last Spectacular Ball Brought to Life in Color Photographs (1903)

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Spanish Flu: A Warning from History

Two years ago historians marked the 100th anniversary of the Spanish Flu, a worldwide pandemic that seemed to be disappearing down the memory hole. Not so fast, said historians, we need to remember the horror. Happy belated anniversary, said 2020, hold my beer. And so here we are. As I write this, the President wheezed through an Address to the Nation which calmed no fears and sent Dow futures tumbling. I scrolled down my news feed to see that Tom Hanks and his wife both have it. Our god is an amoral one, and its noodly appendages touch all.

So let’s put our current moment into perspective with this 10+ minute history on the Spanish Flu from Cambridge University. Here are the numbers: it killed 20 million people according to contemporary accounts. Later scientists and historians revised that number to somewhere between 50 to 100 million.

“This virus killed more people in the first 25 weeks than HIV/AIDS has killed in 25 years,” says historian of medicine Dr. Mary Dobson. And unlike our current COVID-19 strain, this strain of flu went after 20 to 40 year olds with a vengeance. The symptoms were graphic and unpleasant–people drowning in their own phlegm, blood shooting out of noses and ears, people dropping down dead in the street.

Where did it start? Certainly not in Spain–it gained that nickname because the first cases were recorded in the Spanish press. One theory is that it started in Kansas and found its way overseas, from barracks to the frontlines. It might has come from birds or pigs, but scientists still don’t know how it jumps from species to species and how it quickly evolves within humans to infect each other.

Right now, it seems like COVID-19 can subside if countries can work quickly, like in China. But history has a warning too. As Europe and America celebrated Armistice Day at the end of the war, the flu seemed to be going away too. Instead it came roaring back in a second wave, deadlier than the first.

Some famous folks who got the virus but survived included movie stars Lillian Gish and Mary Pickford, right at the height of their fame; President Woodrow Wilson, who was so out of it (though recovering) that some historians blame the weaknesses in the Treaty of Versailles on him. Artist Edvard Munch contracted it (which seems fitting, considering his obsessions) and painted several self-portraits during his illness. Raymond Chandler, Walt Disney, Greta Garbo, Franz Kafka, Georgia O’Keeffe, and Katherine Anne Porter all survived.

Others weren’t so lucky: painter of sensuous, gold leaf paintings Gustav Klimt died from it, as did poet and proto-surrealist Guillaume Apollinaire, and artist Egon Schiele. (And so did Donald Trump’s grandpa).

The Spanish Flu never really went away. There were still cases in the ‘50s, but we humans evolved with it and it became a seasonal type of flu like many others. Flu viruses constantly evolve and mutate, and that’s why it is very difficult to create vaccines that can stop them.

If you’ve read this far, one last thing: GO WASH YOUR HANDS AND STOP TOUCHING YOUR FACE!

Related Content:

Ted Mills is a freelance writer on the arts who currently hosts the artist interview-based FunkZone Podcast and is the producer of KCRW’s Curious Coast. You can also follow him on Twitter at @tedmills, read his other arts writing at tedmills.com and/or watch his films here.

Read More...Watch the Spectacular Hieronymus Bosch Parade, Which Floats Through the Garden of Earthly Delights Painter’s Hometown Every Year

Whether painting scenes of paradise, damnation, or somewhere in between, Hieronymus Bosch realized elaborately grotesque visions that fascinate us more than 500 years later. But no matter how long we gaze upon his work, especially his large-format altarpiece triptychs, most of us wouldn’t want to spend our lives in his world. But a group of dedicated Bosch fans has made it possible to live in it for three days a year, when the annual Bosch Parade floats down the Dommel River. Last year that small waterway hosted “a story in motion, presented on 14 separate tableaux. They shape a universal tale of power and counterforce, battle and rapprochement, chaos and hope. From the chaos after the battle a new order shall emerge.”

All images © Bosch Parade, Ben Niehuis

In practical terms, writes Colossal’s Grace Ebert, that meant “a musical performance played on a partially submerged piano and a scene with two people straddling enormous horns,” as well as a dozen other water-based vignettes that passed through the Dutch town of ‘s‑Hertogenbosch, Bosch’s birthplace and later his namesake.

Everything that rolled down the Dommel was designed by a group of artists selected, according to the parade’s web site, “on the basis of their complementary characteristics, the various disciplines they represent and their clear match with the Bosch Parade artistic ‘DNA’ in the way they work and perform.” As you can see in the 2019 Bosch Parade’s program, the artists’ creations draw on 15th-century conceptions of life, art, technology, and the human body while also taking place unmistakably in the 21st.

Though Bosch’s paintings look alive even in their motionlessness, to appreciate a parade requires seeing it in action. Hence the videos here of the 2015 Bosch Parade: at the top of the post is a short teaser; just above is a longer compilation of some of the event’s most Boschian moments, which puts the painter’s images side-by-side with the floats they inspired. Viewers will recognize elements of The Garden of Earthly Delights, Bosch’s single best-known work, but also of The Haywain Triptych, The Seven Deadly Sins and the Four Last Things, and The Temptations of St. Anthony. As art history buffs know, some of those paintings may or may not have been painted by Bosch himself, but by one of his followers or contemporary imitators.

But to the extent that all these images can inspire modern-day painters, sculptors, musicians, dancers, and spectacle-makers, they enrich the Boschian reality — a reality of water and fire, bodies and body parts, men and monsters, contraptions and projections, and even video games and the internet — that comes to life every summer in ‘s‑Hertogenbosch. Or rather, most every summer: the next Bosch Parade is scheduled not for June of this year but June of 2021. But when that time comes around around it will last for four days, from the 17th through the 20th. That information comes from the parade’s Twitter account, which in the run-up to the event will presumably also post answers to all the most important questions — such as whether next year will feature any live buttock music.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Living Paintings: 13 Caravaggio Works of Art Performed by Real-Life Actors

Flashmob Recreates Rembrandt’s The Night Watch in a Dutch Shopping Mall

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Electronic Musician Shows How He Uses His Prosthetic Arm to Control a Music Synthesizer with His Thoughts

The techno-futurist prophets of the late 20th century, from J.G. Ballard to William Gibson to Donna Haraway, were right, it turns out, about the intimate physical unions we would form with our machines. Haraway, professor emeritus of the History of Consciousness and Feminist Studies at the University of California, Santa Cruz, proclaimed herself a cyborg back in 1985. Whether readers took her ideas as metaphor or proleptic social and scientific fact hardly matters in hindsight. Her voice was predictive of the everyday biometrics and mechanics that lay just around the bend.

It can seem we are a long way, culturally, from the decade when Haraway’s work became required reading in “undergraduate curriculum at countless universities.” But as Hari Kunzru wrote in 1997, “in terms of the general shift from thinking of individuals as isolated from the ‘world’ to thinking of them as nodes on networks, the 1990s may well be remembered as the beginning of the cyborg era.” Three decades later, networked implants that automate medical data tracking and analysis and regulate dosages have become big business, and millions feed their vitals daily into fitness trackers and mobile devices and upload them to servers worldwide.

So, fine, we are all cyborgs now, but the usual use of that word tends to put us in mind of a more dramatic melding of human and machine. Here too, we find the cyborg has arrived, in the form of prosthetic limbs that can be controlled by the brain. Psychologist, DJ, and electronic musician Bertolt Meyer has such a prosthesis, as he demonstrates in the video above. Born without a lower left arm, he received a robotic replacement that he can move by sending signals to the muscles that would control a natural limb. He can rotate his hand 360 degrees and use it for all sorts of tasks.

Problem is, the technology has not quite caught up with Meyer’s need for speed and precision in manipulating the tiny controls of his modular synthesizers. So Meyer, his artist husband Daniel, and synth builder Chrisi of KOMA Elektronik set to work on bypassing manual control altogether, with a prosthetic device that attaches to Meyer’s arm where the hand would be, and works as a controller for his synthesizer. He can change parameters using “the signals from my body that normally control the hand,” he writes on his YouTube page. “For me, this feels like controlling the synth with my thoughts.”

Meyer walks us through the process of building his first prototypes in an Inspector Gadget-meets-Kraftwerk display of analogue ingenuity. We might find ourselves wondering: if a handful of musicians, artists, and audio engineers can turn a prosthetic robotic arm into a modular synth controller that transmits brainwaves, what kind of cybernetic enhancements—musical and otherwise—might be coming soon from major research laboratories?

Whatever the state of cyborg technology outside Meyer’s garage, his brilliant invention shows us one thing: the human organism can adapt to being plugged into the unlikeliest of machines. Showing us how he uses the SynLimb to control a filter in one of his synthesizer banks, Meyer says, “I don’t even have to think about it. I just do it. It’s zero effort because I’m so used to producing this muscle signal.”

Advancements in biomechanical technology have given disabled individuals a significant amount of restored function. And as generally happens with major upgrades to accessibility devices, they also show us how we might all become even more closely integrated with machines in the near future.

via Boing Boing

Related Content:

Neurosymphony: A High-Resolution Look into the Brain, Set to the Music of Brain Waves

Twerking, Moonwalking AI Robots–They’re Now Here

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

Read More...A Medical Student Creates Intricate Anatomical Embroideries of the Brain, Heart, Lungs & More

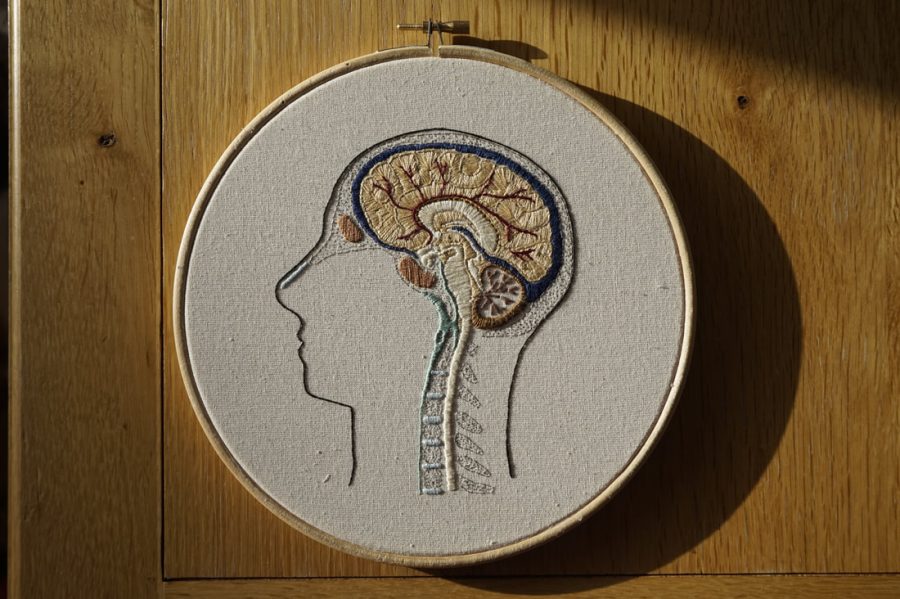

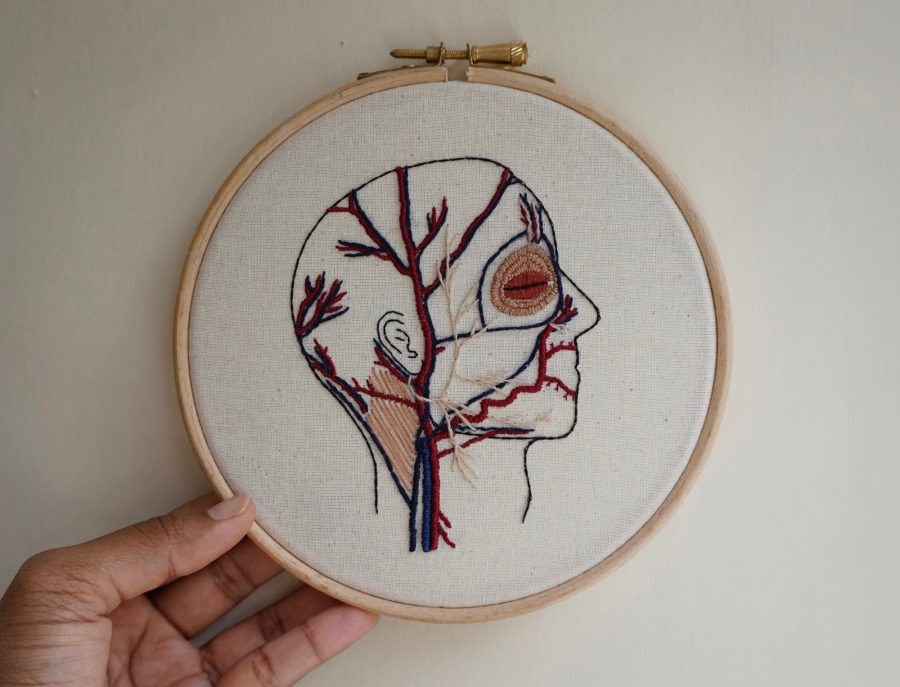

My first thought upon seeing the delicate, anatomy-based work of the 23-year-old embroidery artist and medical student Emmi Khan was that the Girl Scouts must have expanded the categories of skills eligible for merit badges.

(If memory serves, there was one for embroidery, but it certainly didn’t look like a cross-sectioned brain, or a sinus cavity.)

Closer inspection revealed that the circular views of Khan’s embroideries are not quite as tiny as the round badges stitched to high achieving Girl Scouts’ sashes, but rather still framed in the wooden hoops that are an essential tool of this artist’s trade.

Methods both scientific and artistic are a source of fascination for Khan, who began taking needlework inspiration from anatomy as an undergrad studying biomedical sciences. As she writes on her Moleculart website:

Science has particular methods: it is fundamentally objective, controlled, empirical. Similarly, art has particular methods: there is an emphasis on subjectivity and exploration, but there is also an element of regulation regarding how art is created… e.g. what type of needle to use to embroider or how to prime a canvas.

The procedures and techniques adopted by scientists and artists may be very different. Ultimately, however, they both have a common aim. Artists and scientists both want to 1) make sense of the vastness around them in new ways, and 2) present and communicate it to others through their own vision.

A glimpse at the flowers, intricate stitches, and other dainties that populate her Pinterest boards offers a further peek into Khan’s methods, and might prompt some readers to pick up a needle themselves, even those with no immediate plans to embroider a karyotype or The Circle of Willis, the circular anastomosis of arteries at the base of the brain.

The Cardiff-based medical student delights in embellishing her threaded observations of internal organs with the occasional decorative element—sunflowers, posies, and the like…

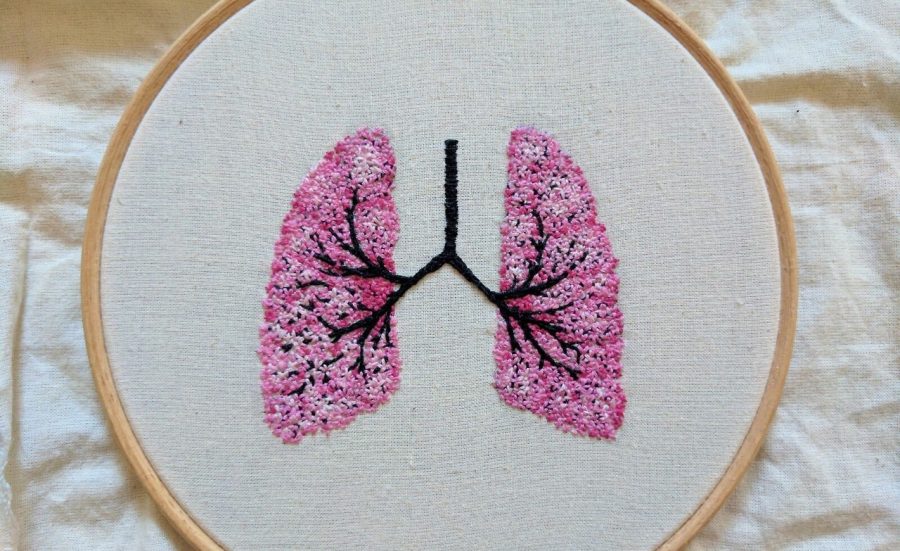

She makes herself available on social media to answer questions on subjects ranging from embroidery tips to her relationship to science as a devout Muslim, and to share works in progress, like a set of lungs that embody the Four Seasons, commissioned by a customer in the States.

To see more of Emmi Khan’s work, including a downloadable anatomical floral heart embroidery pattern, visit Moleculart, her Instagram page, or her Etsy shop.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Behold an Anatomically Correct Replica of the Human Brain, Knitted by a Psychiatrist

An Artist Crochets a Life-Size, Anatomically-Correct Skeleton, Complete with Organs

Watch Nina Paley’s “Embroidermation,” a New, Stunningly Labor-Intensive Form of Animation

Ayun Halliday is an author, illustrator, theater maker and Chief Primatologist of the East Village Inky zine. Join her in NYC on Monday, February 3 when her monthly book-based variety show, Necromancers of the Public Domain celebrates New York: The Nation’s Metropolis (1921). Follow her @AyunHalliday.

Read More...Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast #26 Discusses Alan Moore’s Watchmen Comic and the HBO Show with Cornell Psychology Professor David Pizarro

Perhaps the most lauded graphic novel has been sequelized for HBO, and amazingly, it turned out pretty darn well (with a 96% Rotten Tomatoes rating!).

Your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt are joined by the Cornell’s David Pizarro, host of the popular Very Bad Wizards podcast. We consider Alan Moore’s 1986 graphic novel, the 2009 Zack Snyder film, and of course mostly the recently completed (we hope) show by Damon Lindelof, the creator of Lost and The Leftovers.

How does Moore’s idiosyncratic writing style translate to the screen? Did the show make best use of its nine hours? Are there other stories in this alternate history that should still be told, perhaps to reflect on other recurrent social ills or crises of whatever moment might be depicted? Was Lindelof really the guy to tell this story about race, and does making the show about racism (which is bad!) undermine Moore’s rejection of (morally) black-and-white heroes and villains?

Some of the articles we used to warm up for this discussion included:

- “Some Watchmen Fans Are Mad that HBO’s Version Is Political. But Watchmen Has Always Been Political” by Alex Abad-Santos

- “How HBO’s ‘Watchmen’ Can Avoid the Misogynistic Missteps of Its Past” by Rosie Knight

- “The Right-Wing Troll Backlash Against HBO’s Watchmen Is Hilariously Stupid” by Matt Miller

- “How ‘Watchmen’s’ Misunderstanding of Vietnam Undercuts its Vision of Racism” by Viet Thanh Nguyen

- “Why We Don’t Want to Watch Watchmen Season 2” by David Opie

- “When Sex Scenes Go Wrong: Zack Snyder’s Watchmen“ by Jim Vorel

You might want to also check out HBO’s Watchmen page, which includes extra essays and the official podcast with Damon Lindelof commenting on the episodes.

Follow Dave @peez. Hear him on The Partially Examined Life, undoubtedly the apex of his professional career.

This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Read More...A Map of the Disney Entertainment Empire Reveals the Deep Connections Between Its Movies, Its Merchandise, Disneyland & More (1967)

We all remember the first Disney movie we ever saw. In most of our childhoods, one Disney movie led to another, which stoked in us the desire for Disney toys, Disney games, Disney comics, Disney music, and so on. If we were lucky, we might also take a trip to Disneyland or one of its descendants elsewhere in the world. Many of us spent the bulk of our youngest years as happy residents of the Disney entertainment empire; some of us, into adulthood or even old age, remain there still.

Die-hard Disney fans appreciate that the world of Disney — comprising not just films and theme parks but television shows, printed matter, attractions on the internet, and merchandise of nearly every kind — is too vast ever to comprehend, let alone fully explore.

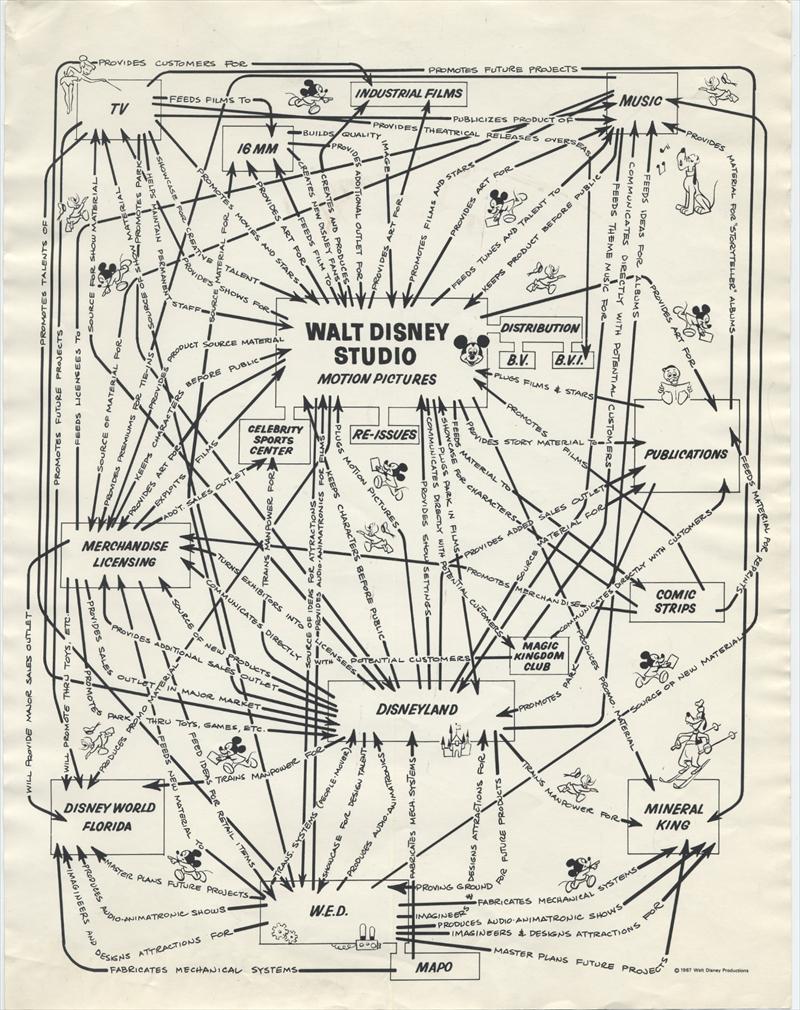

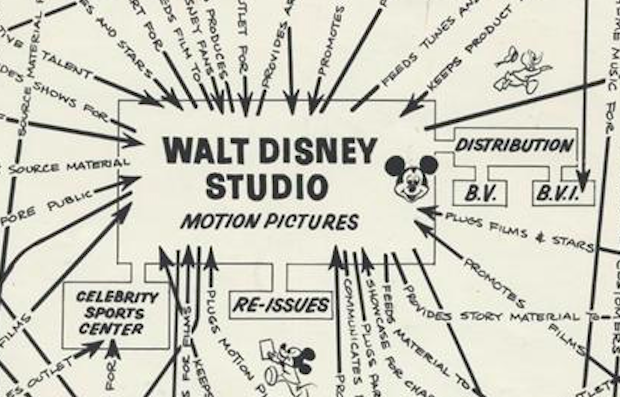

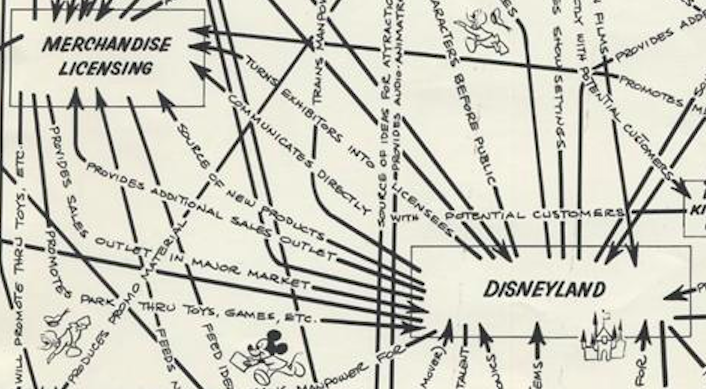

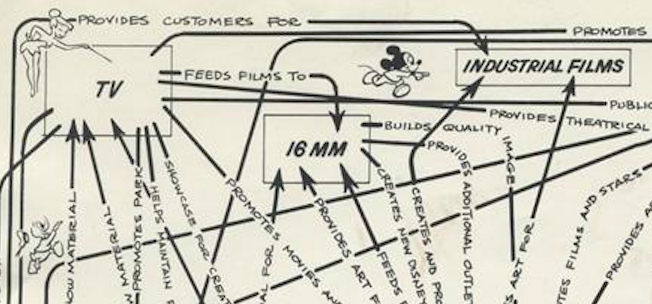

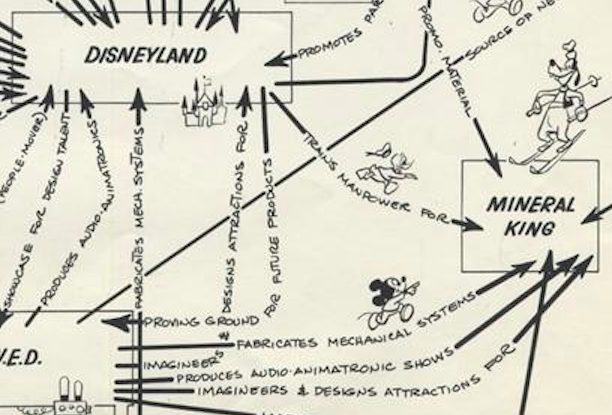

It was already big half a century ago, but not too big to grasp. You can see the whole of the operation laid out in this organizational synergy diagram created by Walt Disney Productions in 1967. Depicting “the many and varied synergistic relationships between the divisions of Walt Disney Productions,” the information graphic reveals the links between each division.

Along the arrowheaded lines indicating the flows of manpower, material, and intellectual property, “short textual descriptions show what each division supplies and contributes to the others.” The motion picture division “feeds tunes and talent” to the music division, for example, which “promotes premiums for tie-ins” to the merchandise licensing department, which “feeds ideas for retail items” to WED Enterprises (the holding company founded by Walt Disney in 1950), which produces “audio-animatronics” for Disneyland.

Some of the nexuses on the diagram will be as familiar as Mickey Mouse, Goofy, Tinkerbell, and the characters cavorting here and there around it. Others will be less so: the 16-millimeter films division, for instance, which would eventually be replaced by a colossal home-video division (itself surely being eaten into, now, by streaming). The Celebrity Sports Center, an indoor entertainment complex outside Denver, closed in 1994. MAPO refers to a theme-park animatronics unit formed in the 1960s with the profits of Mary Poppins (hence its name) and dissolved in 2012. And as for Mineral King, a proposed ski resort in California’s Sequoia National Park, it was never even built.

“The ski resort was one of several ambitious projects that Walt Disney spearheaded in the years before his death in 1966,” writes Nathan Masters at Gizmodo. But as the size of the Mineral King plans grew, wilderness-activist opposition intensified. After years of opposition by the Sierra Club, as well as the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act 1970 and the National Parks and Recreation Act of 1978, corporate interest in the project finally fizzled out. Though that would no doubt have come as a disappointment to Walt Disney himself, he might also have known to keep the failure in perspective. As he once said of the empire bearing his name, “I only hope that we never lose sight of one thing — that it was all started by a mouse.”

h/t Eli and via Howard Lowery

Related Content:

Disneyland 1957: A Little Stroll Down Memory Lane

How Walt Disney Cartoons Are Made: 1939 Documentary Gives an Inside Look

Walt Disney Presents the Super Cartoon Camera

Disney’s 12 Timeless Principles of Animation

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...Sportscaster Dave Revsine (Big 10 Network) Joins Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast to Discuss the Role of Sports in Pop Culture

How is spectator sports different from other types of entertainment? Dave Revsine (lead studio host for the Big Ten Network and former ESPN anchor) joins your hosts Mark Linsenmayer, Erica Spyres, and Brian Hirt to discuss the various sources of appeal, team identification, existing in a sports-filled world as a non-fan, watching vs. playing, human interest stories, sports films, and more.

Some of the articles we looked at to prepare included:

- “Why Do We Care About Sports So Much” by Christine Emba

- “The Science Behind Our Love of March Madness” by Marco Iacoboni

- “Trying to Understand 50% of America: Sports Fans” by Carolyn Canetti

- “5 Reasons People Hate Sports — That Sports Fans Secretly Understand” by Logan Rhoades

- “The Art of Telling Human Interest Stories at the Olympics” from The Frame

- “10 Great Sports Movies For Non-Sports Fans” by Jason Bailey (there are several other articles out there on this if you want to search for them)

- “The Non-Football Fan’s Guide to Enjoying the Super Bowl” by Dan Steinberg

The first two links above were part of a series of 2016 editorials in the Washington Post coinciding with March Madness. As the whole series is definitely worth a look, just follow the links at the bottom of those articles.

Dave wrote a book you might want to look at called The Opening Kickoff: The Tumultuous Birth of a Football Nation. Follow him on Twitter @BTNDaveRevsine.

This episode includes bonus discussion that you can only hear by supporting the podcast at patreon.com/prettymuchpop. This podcast is part of the Partially Examined Life podcast network.

Pretty Much Pop: A Culture Podcast is the first podcast curated by Open Culture. Browse all Pretty Much Pop posts or start with the first episode.

Revisiting Band Aid’s Cringe-Inducing 1984 Single, “Do They Know It’s Christmas?”

We all know, don’t we, that the 1984 charity hit “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” qualifies as possibly the worst Christmas song ever recorded? Does that go too far? The song’s writer, Bob Geldof, went even further, once saying, “I am responsible for two of the worst songs in history. One is ‘Do They Know It’s Christmas?’ and the other one is ‘We Are the World.’”

There’s no objective measure for such a thing, but I’m not inclined to disagree, with due respect for the millions Geldof, co-organizer and co-producer Midge Ure, and British celebrity supergroup Band Aid raised to feed victims of famine in Ethiopia in the mid-80s. Revisiting the lyrics now, I’m shocked to find they’re even more ridiculous and cringe-inducing than I remembered.

We can quickly dispense with the absurdity of the title. As an exasperated Spotify employee helpfully pointed out recently in a series of annotations, “the people of Ethiopia probably did know it was Christmas—it’s one of the oldest Christian nations in the world” with a majority Christian population.

The song’s aid recipients are referred to as “the other ones” who live in “a world of dread and fear.” Listeners are enjoined to “thank God it’s them instead of you.” And two years after Toto’s “Africa,” Band Aid manages to deliver the clumsiest, most ill-informed stanza perhaps ever written about the continent:

And there won’t be snow in Africa

This Christmas time

The greatest gift they’ll get this year is life

Where nothing ever grows

No rain or rivers flow

Do they know it’s Christmas time at all?

Troublingly, the song “peddles myths about the cause of the famine,” writes Greg Evans at The Independent, “suggesting it was down to a drought, rather than the corrupt government misusing international aid.”

But it’s Christmas, as you probably know, so let’s not be too hard on “Do They Know It’s Christmas?” The artists who participated, including George Michael, Bono, Boy George, Sting, and many others had a significant impact on the entertainment industry’s role in international aid, for good and ill. The song was re-recorded three times, in 1989, 2004, and 2014, and it has become, believe it or not, “the second bestselling single in Britain’s history,” Laura June points out at The Outline.

Evans notes that “a reported £200m was raised via sales of the single which went towards the relief fund and it later went on to inspire the iconic Live Aid concert in July 1985, which raised a further £150m.” (Some of that money, it was later discovered, inadvertently made it into the hands of Ethiopia’s corrupt government.) Other benefit events, like Farm Aid in the U.S., would follow Geldof and Urge’s lead, and the model proved to be an enduring way for artists to support causes they cared about.

See the unbearably earnest original video at the top of the post and, just above, a thirty-minute making of film with a who’s who of mid-1980s British pop royalty learning to sing “let them know it’s Christmas time again” together.

Related Content:

Stream a Playlist of 68 Punk Rock Christmas Songs: The Ramones, The Damned, Bad Religion & More

Hear Paul McCartney’s Experimental Christmas Mixtape: A Rare & Forgotten Recording from 1965

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness

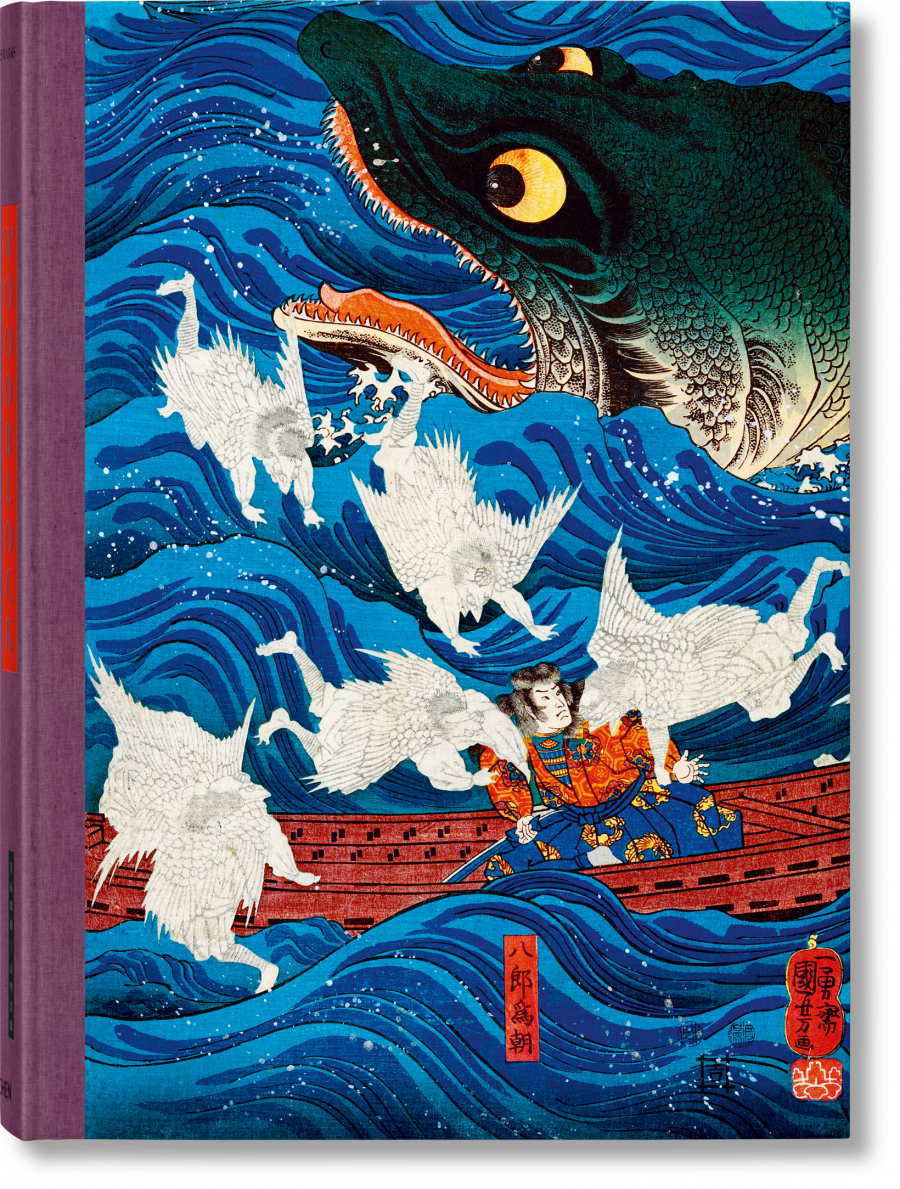

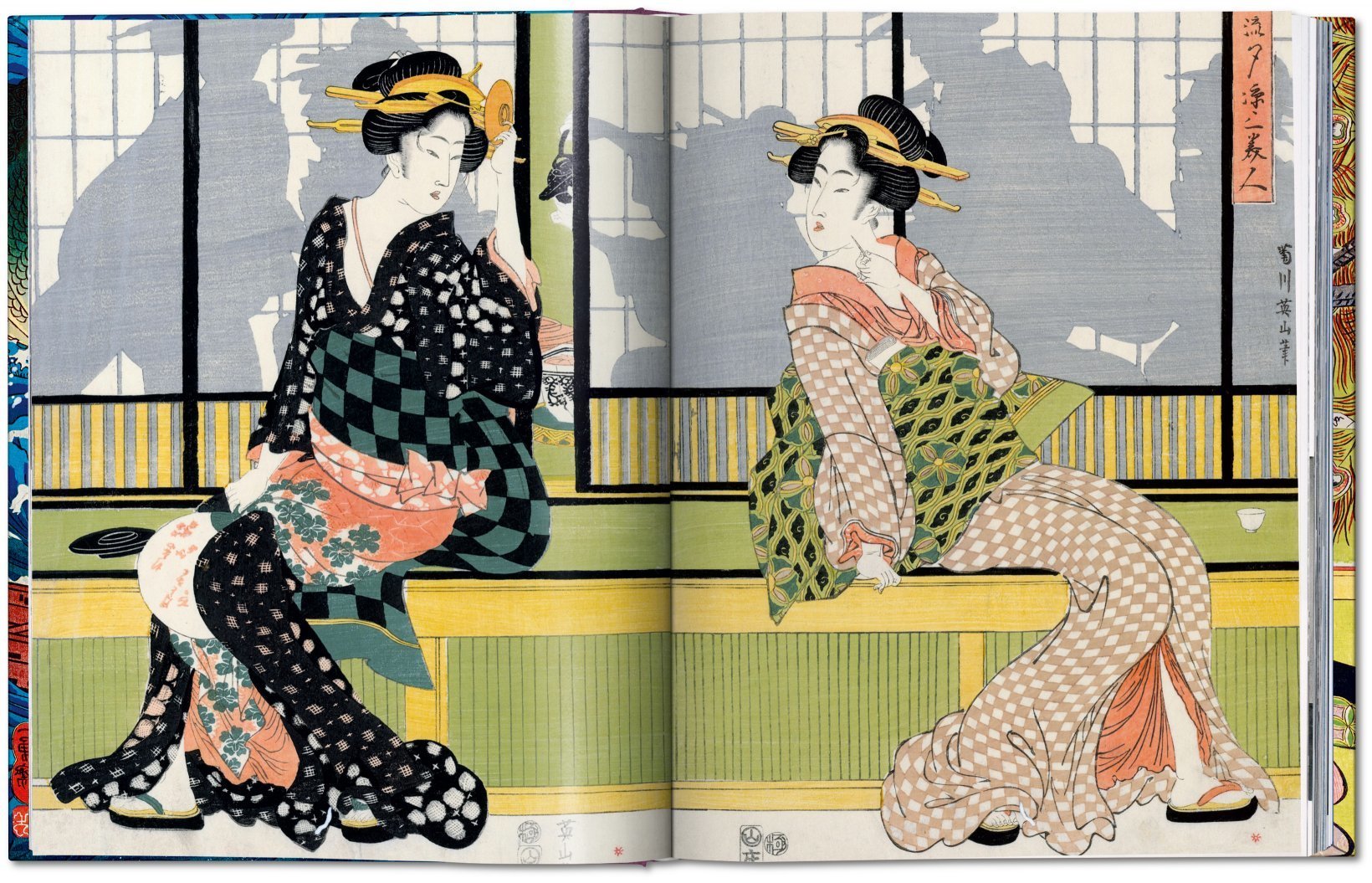

Read More...A Beautiful New Book of Japanese Woodblock Prints: A Visual History of 200 Japanese Masterpieces Created Between 1680 and 1938

Japanese woodblock prints, especially in the style known in Japanese as ukiyo‑e, or “pictures of the floating world,” portray the social, natural, and supernatural realms in a way no other art form ever has. They also repay the attention you give them, one reason we here on Open Culture have tried to share with you every opportunity to download them — from the archive at Ukiyo‑e.org, for example, or at the Library of Congress — and build your own digital collection.

But appreciating Japanese woodblock prints on a screen is one thing, and appreciating them in large-scale reproductions on paper is quite another. At least that’s one implicit premise of the book Japanese Woodblock Prints (1680–1938), newly published by Taschen.

As a publisher, Taschen has made its formidable name in part by collecting between two covers the lesser-known work of famous artists of the recent past: Andy Warhol’s hand-illustrated books, for example, or Salvador Dalí’s cookbook and tarot deck.

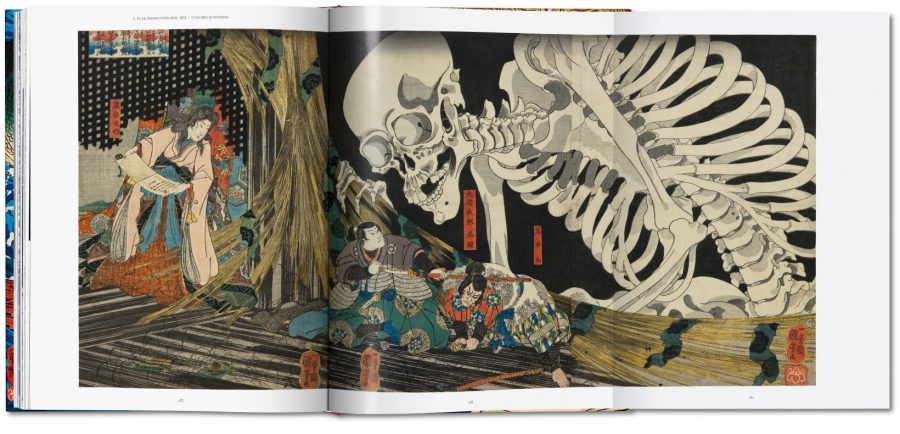

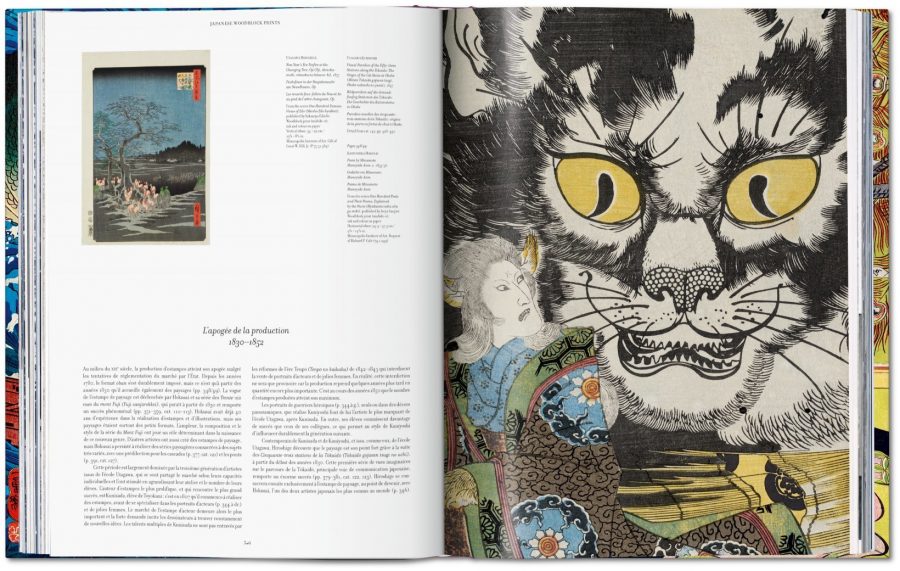

Never an outfit to fear accusations of immodesty, Taschen’s projects also include “XXL books” like a 500-page, 14-pound volume on Jean-Michel Basquiat. Surpassing even that book in length by more than 200 pages, Japanese Woodblock Prints contains, according to Taschen’s official site, an artistic reality where “breathtaking landscapes exist alongside blush-inducing erotica; where demons and otherworldly creatures torment the living; and where sumo wrestlers, kabuki actors, and courtesans are rock stars.”

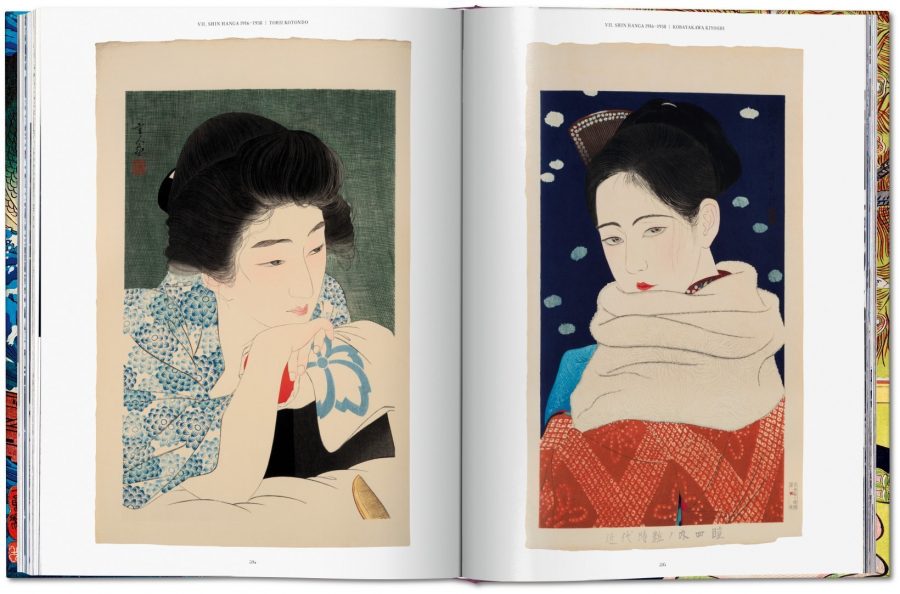

“For this tome, Taschen spent three years reproducing woodblock prints from museums and private collections from around the world,” writes Colossal’s Andrew Lasane. “Written by Andreas Marks, head of the Japanese and Korean Art Department at the Minneapolis Institute of Art, the book is divided chronologically into seven chapters beginning with the 17th century early masters and concluding with the Shin-hanga movement.” (That last is a late 19th- and early 20th-century woodblock style, in which we once featured renderings of Hayao Miyazaki’s characters.)

No matter our temporal and cultural distance from the Japanese masters of ukiyo‑e, we’ve nearly all been captivated by their work at one time or another, most often when we run across pieces of it online. With Japanese Woodblock Prints, Taschen means to get those of us who prefer print even more captivated — and at the same time, to teach us more than a little about the cultural and historical context of all these landscapes, cityscapes, monsters, beauties, and historical figures at which we marvel.

If you want to pick up a copy of this artistic work, you can make a purchas on Amazon.

via Colossal

Related Content:

Enter a Digital Archive of 213,000+ Beautiful Japanese Woodblock Prints

Download 2,500 Beautiful Woodblock Prints and Drawings by Japanese Masters (1600–1915)

Download Hundreds of 19th-Century Japanese Woodblock Prints by Masters of the Tradition

Based in Seoul, Colin Marshall writes and broadcasts on cities, language, and culture. His projects include the book The Stateless City: a Walk through 21st-Century Los Angeles and the video series The City in Cinema. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on Facebook.

Read More...