Image via Wikimedia Commons

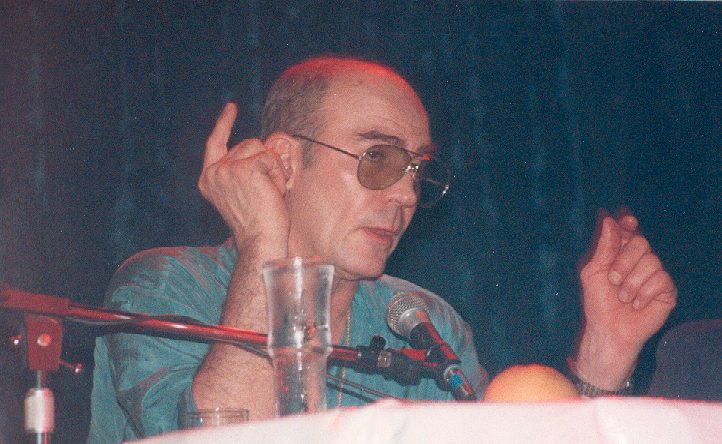

Most readers know Hunter S. Thompson for his 1971 book Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas: A Savage Journey to the Heart of the American Dream. But in over 45 years of writing, this prolific observer of the American scene wrote voluminously, often hilariously, and usually with deceptively clear-eyed vitriol on sports, politics, media, and other viciously addictive pursuits. (“I hate to advocate drugs, alcohol, violence, or insanity to anyone,” he famously said, “but they’ve always worked for me.”) His distinctive style, often imitated but never replicated, all but forced the coining of the term “gonzo” journalism. But what could define it? One clue comes in Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas itself, when Thompson reflects on his experience in the city, ostensibly as a reporter: “What was the story? Nobody had bothered to say. So we would have to drum it up on our own. Free Enterprise. The American Dream. Horatio Alger gone mad on drugs in Las Vegas. Do it now: pure Gonzo journalism.”

You’ll find out more in the Paris Review’s interview with Thompson, in which he recounts once feeling that “journalism was just a ticket to ride out, that I was basically meant for higher things. Novels.” Sitting down to begin his proper literary career, Thompson took a quick job writing up the Hell’s Angels, which let him get over “the idea that journalism was a lower calling. Journalism is fun because it offers immediate work. You get hired and at least you can cover the f&cking City Hall. It’s exciting.” And then came the real epiphany, after he went to cover the Kentucky Derby for Scanlan’s: “Most depressing days of my life. I’d lie in my tub at the Royalton. I thought I had failed completely as a journalist. Finally, in desperation and embarrassment, I began to rip the pages out of my notebook and give them to a copyboy to take to a fax machine down the street. When I left I was a broken man, failed totally, and convinced I’d be exposed when the stuff came out.”

Indeed, the exposure came, but not in the way he expected. Below, we’ve collected ten of Thompson’s articles freely available online, from those early pieces on the Hell’s Angels and the Kentucky Derby to others on the 1972 Presidential race, the Honolulu Marathon, Richard Nixon, and wee-hour conversations with Bill Murray. But don’t take these subjects too literally; Thompson always had a way of finding something even more interesting in exactly the opposite direction from whatever he’d initially meant to write about. And that, perhaps, reveals more about the gonzo method than anything else.

“The Motorcycle Gangs: Losers and Outsiders” (The Nation, 1965) The article that would become the basis for Thompson’s first book, Hell’s Angels: The Strange and Terrible Saga of the Outlaw Motorcycle Gangs. “When you get in an argument with a group of outlaw motorcyclists, you can generally count your chances of emerging unmaimed by the number of heavy-handed allies you can muster in the time it takes to smash a beer bottle. In this league, sportsmanship is for old liberals and young fools.”

Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas (Rolling Stone, 1971) The Gonzo journalism classic first appeared as a two-part series in Rolling Stone magazine in November 1971, complete with illustrations from Ralph Steadman, before being published as a book in 1972. Rolling Stone has posted the original version on its web site.

“Fear and Loathing on the Campaign Trail in ’72″ (Rolling Stone, 1973) Excerpts from Thompson’s book of nearly the same name, an examination of Democratic Party candidate George McGovern’s unsuccessful bid for the Presidency that McGovern’s campaign manager Frank Mankiewicz called “the least factual, most accurate account” in print. “My own theory, which sounds like madness, is that McGovern would have been better off running against Nixon with the same kind of neo-‘radical’ campaign he ran in the primaries. Not radical in the left/right sense, but radical in a sense that he was coming on with a new… a different type of politician… a person who actually would grab the system by the ears and shake it.”

“The Curse of Lono” (Playboy, 1983) Thompson and Steadman’s assignment from Running magazine to cover the Honololu marathon turns into a characteristically “terrible misadventure,” this one even involving the old Hawaiian gods. “It was not easy for me, either, to accept the fact that I was born 1700 years ago in an ocean-going canoe somewhere off the Kona Coast of Hawaii, a prince of royal Polynesian blood, and lived my first life as King Lono, ruler of all the islands, god of excess, undefeated boxer. How’s that for roots?”

“He Was a Crook” (Rolling Stone, 1994) Thompson’s obituary of, and personal history of his hatred for, President Richard M. Nixon. “Some people will say that words like scum and rotten are wrong for Objective Journalism — which is true, but they miss the point. It was the built-in blind spots of the Objective rules and dogma that allowed Nixon to slither into the White House in the first place.

“Doomed Love at the Taco Stand” (Time, 2001) Thompson’s adventures in California, to which he has returned for the production of Terry Gilliam’s film adaptation of Fear and Loathing in Las Vegas starring Johnny Depp. “I had to settle for half of Depp’s trailer, along with his C4 Porsche and his wig, so I could look more like myself when I drove around Beverly Hills and stared at people when we rolled to a halt at stoplights on Rodeo Drive.”

“Fear & Loathing in America” (ESPN.com, 2001) In the immediate aftermath of 9/11, Thompson looks out onto the grim and paranoid future he sees ahead. “This is going to be a very expensive war, and Victory is not guaranteed — for anyone, and certainly not for anyone as baffled as George W. Bush.”

“Prisoner of Denver” (Vanity Fair, 2004) A chronicle of Thompson’s (posthumously successful) involvement in the case of Lisl Auman, a young woman he believed wrongfully imprisoned for the murder of a police officer. “ ‘We’ is the most powerful word in politics. Today it’s Lisl Auman, but tomorrow it could be you, me, us.”

“Shotgun Golf with Bill Murray” (ESPN.com, 2005) Thompson’s final piece of writing, in which he runs an idea for a new sport —combining golf, Japanese multistory driving ranges, and the discharging of shotguns — by the comedy legend at 3:30 in the morning. “It was Bill Murray who taught me how to mortify your opponents in any sporting contest, honest or otherwise. He taught me my humiliating PGA fadeaway shot, which has earned me a lot of money… after that, I taught him how to swim, and then I introduced him to the shooting arts, and now he wins everything he touches.”

Related Content:

Hunter S. Thompson’s Harrowing, Chemical-Filled Daily Routine

Hunter S. Thompson Calls Tech Support, Unleashes a Tirade Full of Fear and Loathing (NSFW)

Johnny Depp Reads Letters from Hunter S. Thompson (NSFW)

Hunter S. Thompson Remembers Jimmy Carter’s Captivating Bob Dylan Speech (1974)

Colin Marshall hosts and produces Notebook on Cities and Culture and writes essays on cities, Asia, film, literature, and aesthetics. He’s at work on a book about Los Angeles, A Los Angeles Primer. Follow him on Twitter at @colinmarshall or on his brand new Facebook page.