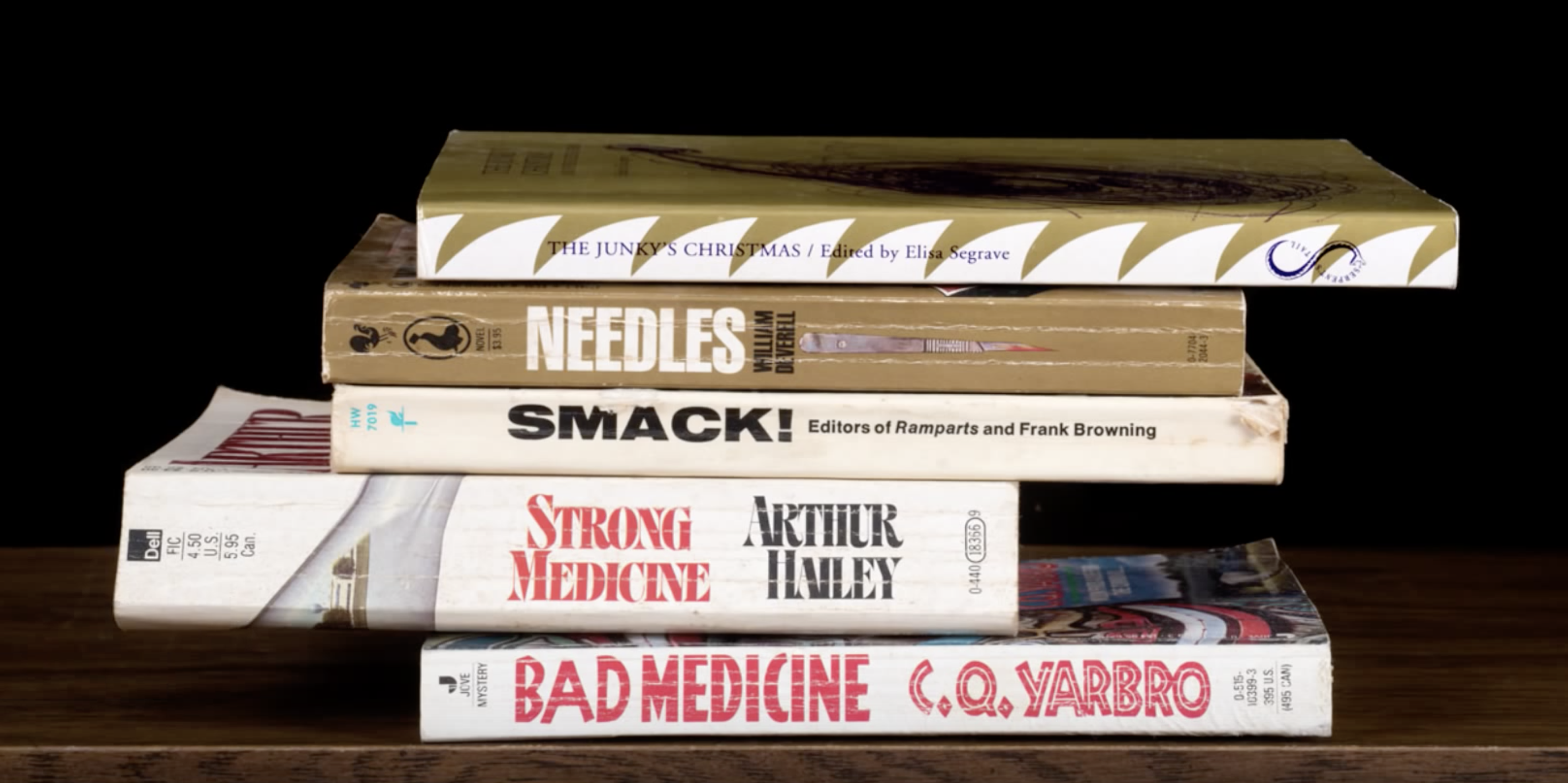

Every recording medium works as a metonym for its era: the term “LP” conjures up associations with a broad musical period of classic rock ‘n’ roll, soul, doo-wop, R&B, funk, jazz, disco etc.; we talk of the “CD era,” dominated by dance music and hip-hop; the 45 makes us think of jukeboxes, diners, and sock-hops; and the cassette, well… at least one subgenre of music, what John Peel called “shambling,” jangly, lo-fi pop, came to be known by the name “C86,” the title of an NME compilation, short for “Cassette, 1986.” (Readers of the magazine had to clip coupons and send money by postal mail to receive a copy of the tape.)

Soon, however, fewer and fewer people will remember the age of the 78rpm record, the preferred vehicle for the music of the early 20th century. From classical and opera to blues, bluegrass, swing, ragtime, gospel, Hawaiian, and holiday novelties the 78 epitomizes the sounds of its heyday as much as any of the media mentioned above.

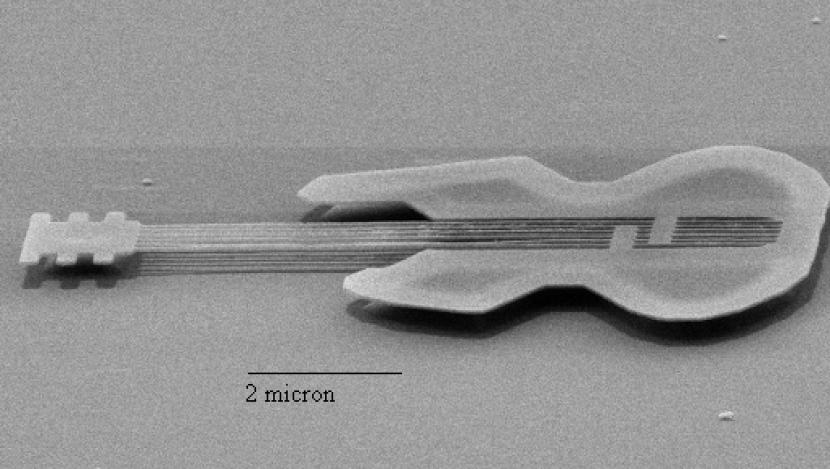

While cassettes recently made a nostalgic comeback, and turntables are found in every big box store, we’re generally not equipped to play back 78s. These are brittle records made from shellac, a resin secreted by beetles. They were often played on appliances that doubled as quality parlor furniture.

Thanks now to the Internet Archive, that stalwart of digital cataloguing and curation, we can play twenty five thousand 78s and immerse ourselves in the early 20th century, whether for research purposes or pure enjoyment. Previous efforts at preservation have “restored or remastered… commercially viable recordings” on LP or CD, writes The Great 78 Project, the archive’s volunteer program to digitize musical history. The current effort seeks to go beyond popularity and collect everything, from the rarest and strangest to the already historic. “I want to know what the early 20th century sounded like,” writes Internet Archive founder Brewster Kahle, “Midwest, different countries, different social classes, different immigrant communities and their loves and fears.”

You can hear several selections here, and thousands more at this archive of 78s uploaded by audio-visual preservation company, George Blood, L.P. Other 78rpm archives from volunteer collectors and the ARChive of Contemporary Music are being digitized and uploaded as well. You’ll note the recordings are often submerged in crackle and hiss, and generally lack bass and treble (most playback systems of the time could not reproduce the lower and higher ends of the audible spectrum). “We have preserved the often very prominent surface noise and imperfections,” the Archive writes, “and included files generated by different sizes and shapes of stylus to facilitate different kinds of analysis.” Different playback systems could produce markedly different sounds, and the recordings were not always strictly 78rpm.

These conditions of the transfer ensure that we roughly hear what the first audiences heard, though the records’ age and our penchant for 7 speaker audio systems introduce some new variables. None of these recordings were even made in stereo. The 78 period, notes Yale Library, lasted between 1898 and the late 1950s, when the 33 1/2 rpm long-playing record fully edged out the older model. For approximately fifty years, these records carried recorded music, sound, and speech into homes around the world. “What is this?” Kahle asks of this formidable digitization project. “A reference collection? A collector’s dream? A discovery radio station? The soundtrack of the early 20th century?” All of the above. To learn more about The Great 78 Project, including the technical details of the transfer and how you can carefully package up and mail in your own 78rpm records, visit their Preservation page.

Related Content:

BBC Launches World Music Archive

DC’s Legendary Punk Label Dischord Records Makes Its Entire Music Catalog Free to Stream Online

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness