Fitting, I suppose, that the only creative meeting of the minds between two of the twentieth century’s best-known film directors took place on a project about the problem of nonhuman intelligence and the dangerous excesses of human ingenuity. For both Stanley Kubrick and Steven Spielberg, these were conflicts rich with inherent dramatic possibility. One of the many important differences between their approaches, however, is a stark one. As many critics of AI: Artificial Intelligence—the film Kubrick had in development since the 70s, then handed off to Spielberg before he died—have pointed out, Kubrick mined conflict for philosophical insights that can leave viewers intriguingly puzzled, if emotionally chilled; Spielberg pushes his drama for maximum emotional impact, which either warms audiences’ hearts or turns their stomachs, depending on their disposition.

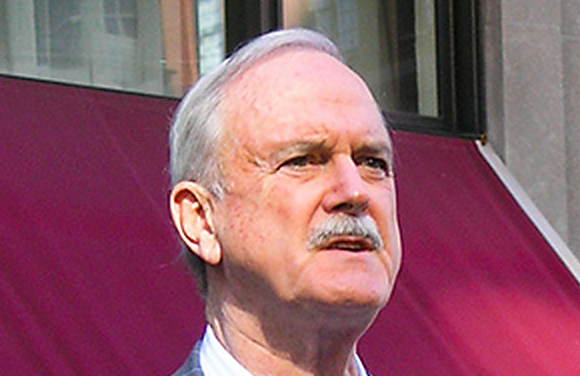

In the latter camp, we can firmly place Monty Python alumnus and cult director Terry Gilliam. In the short clip at the top of the post, Gilliam explicates “the main difference” as he sees it between Spielberg and Kubrick. Spielberg’s films are “comforting,” they “give you answers, always, the films are… answers, and I don’t they’re very clever answers.” Kubrick’s movies, on the other hand, always leave us with unanswerable questions—riddles that linger indefinitely and that no one viewer can satisfactorily solve. So says Gilliam, an infamously quixotic director whose pursuit of a vision uniquely his own has always trumped any commercial appeal his work might have. Most successful films, he argues, “tie things up in neat little bows.” For Gilliam, this is a cardinal sin: “the Kubricks of this world, and the great filmmakers, make you go home and think about it.” Certainly every fan of Kubrick will admit as much—as will those who don’t like his films, often for the very same reasons.

To make his point, Gilliam quotes Kubrick himself, who issued an incisive critique of Spielberg’s Nazi drama Schindler’s List, saying that the movie “is about success. The Holocaust was about failure”—the “complete failure,” Gilliam adds, “of civilization.” Not a subject one can, or should, even attempt to spin positively, one would think. As an example of a Kubrick film that leaves us with an epistemological and emotional vortex, Gilliam cites the artificial intelligence picture the great director did finish, 2001: A Space Odyssey. To see in action how these two directors’ approaches greatly diverge, watch the endings of both Schindler’s List and 2001, above. Of course the genre and subject matter couldn’t be more different—but that aside, you’ll note that neither could Kubrick and Spielberg’s visual languages and cinematic attitudes, in any of their films.

Despite this vast divide—between Spielberg’s “neat little bows” and Kubrick’s headtrips—it might be argued that their one collaboration, albeit a posthumous one for Kubrick, shows them working more closely together than seems possible. Or so argues Noel Murray in a fascinating critical take on AI, a film that perhaps deserves greater appreciation as an “unnerving,” existentialist, and Kubrick-ian turn for Spielberg, that master of happy endings.

Related Content:

Terry Gilliam Reveals the Secrets of Monty Python Animations: A 1974 How-To Guide

Stanley Kubrick’s Rare 1965 Interview with The New Yorker

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness