Click here to view the image in a larger format.

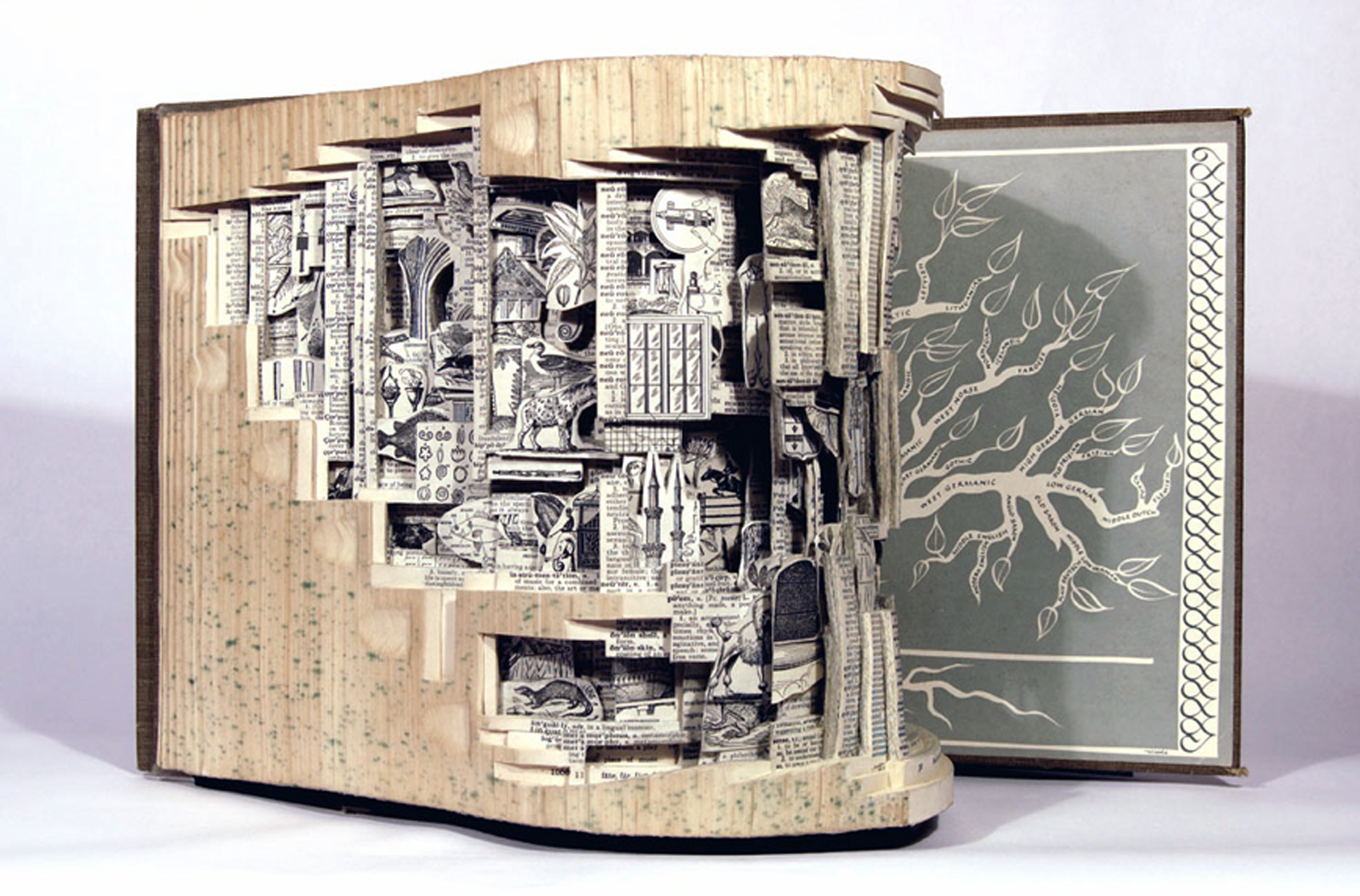

In 1931, Caltech invited Albert Einstein to spend some time on their campus, with the hopes that he might eventually join their faculty. While in Southern California, he met Charlie Chaplin, took a photo with an Einstein puppet, enjoyed the mild winter, ruffled a few conservative feathers, then eventually left town. On the train ride back across the country, he visited the Hopi House, near the Grand Canyon, where he posed for a picture with members of the Hopi tribe. The website Hanksville.org revisits the classic photograph (apparently taken by Eugene O. Goldbeck) that documented his short visit:

There are several striking things about this photograph that deserve mention. It is clear that the headdress that has been placed on Professor Einstein’s head and the pipe he has been given to hold have no relationship to the Indians in this photograph. These Indians are Hopis from the relatively nearby Hopi pueblos while the headdress and pipe belong to the Plains Indian culture.… The Hopis in this picture were employees of the Fred Harvey Company who demonstrated their arts there and, no doubt, posed for many other pictures with tourists.

Besides Albert Einstein and his wife, there are 3 adult Hopis and one Hopi child in the photograph. Einstein is holding the hand of a young Hopi girl in a very natural manner; she is clutching something tightly in her other hand and is quite intent upon something outside the frame. Prof. Einstein’s attraction to children is seen in several other unofficial photographs. He loved children and felt quite comfortable with them. The two men on the left side of the photograph were there to facilitate the Einsteins’ trip. The man on the left is J. B. Duffy, General Passenger Agent of the ATSF (the famous Atichson, Tokepa and Santa Fe Railroad); the other man is Herman Schweizer, Head of Fred Harvey Curio, normally stationed in Albuquerque. He may have spoken German and was therefore present because Prof. Einstein was not completely comfortable yet with English.

According to the Einstein Almanac, the Hopi “gave Einstein a peace pipe, recognizing his pacifism, and dubbed him the ‘Great Relative.’ ” You can see the pipe on display in the photo.

As one website observed, what’s perhaps most notable about the historic image is this: It captures layers of commodification/fetishization. Here stands the most fetishized intellectual of the 20th century posing with one of the most fetishized peoples. Or maybe that’s just overthinking things.

Note: Some sources date the classic photo back to 1922, but that seems less plausible. The Harry Ransom Center provides an image available for download here.

Follow us on Facebook, Twitter and Google Plus and share intelligent media with your friends. Or better yet, sign up for our daily email and get a daily dose of Open Culture in your inbox.

Related Content:

Listen as Albert Einstein Calls for Peace and Social Justice in 1945

Albert Einstein Holding an Albert Einstein Puppet (Circa 1931)

“Do Scientists Pray?”: A Young Girl Asks Albert Einstein in 1936. Einstein Then Responds.

Einstein for the Masses: Yale Presents a Primer on the Great Physicist’s Thinking

The Musical Mind of Albert Einstein: Great Physicist, Amateur Violinist and Devotee of Mozart

Free Physics Courses in our Collection of 1100 Free Online Courses