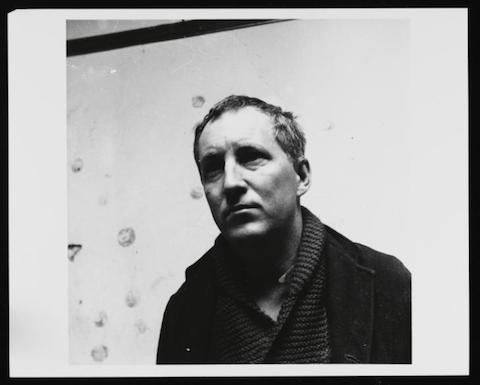

Photograph of Nigel Henderson via Nigel Henderson Estate

If you’re like me, one of the first items on your itinerary when you hit a new city is the art museums. Of course one, two, even three or four visits to the world’s major collections can’t begin to exhaust the wealth of painting, sculpture, photography, and more contained within. Rotating and special exhibits make taking it all in even less feasible. That’s why we’re so grateful for the digital archives that institutions like the Getty, LA County Museum of Art, the Metropolitan Museum of Art, the National Gallery, and the British Library make available free online. Now another museum, Britain’s Tate Modern, gets into the digital archive arena with around 70,000 digitized works of art in their online gallery.

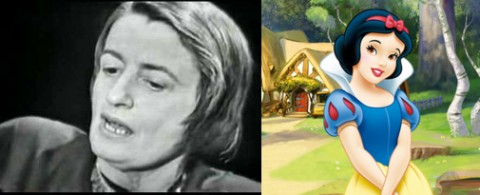

“Sketch of the bus stop” from the estate of Josef Herman

But wait, there’s more. Much more. A separate digital archive—the Tate’s Archives & Access project—offers up a trove of materials you’re unlikely to encounter much, if at all, in their physical spaces. That’s because this collection digitizes little-seen “artists’ materials, including photographs, sketchbooks, diaries, letters and objects, documenting the lives and working processes of British born and émigré artists, from 1900 to the present.” These include, writes The Guardian, “the love letters of painter Paul Nash, the detailed sculpture records of Barbra Hepworth, and 3,000 photographs by Nigel Henderson, providing a behind-the-scenes backstage look at London’s 1950s jazz scene.” Thus far, the Tate has uploaded about 6,000 items, “including 52 collections relating to 79 artists.” At the Tate archive, you’ll find photographs like that of painter and photographer Nigel Henderson (see top of the post) and also paintings by the highly regarded Polish-British realist, Josef Herman (right above).

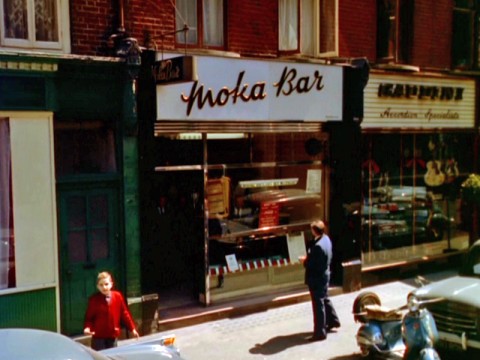

“Squared-up drawings of soldiers” via The estate of David Jones

You’ll find preliminary sketches like the 1920–21 Squared-up drawings of soldiers by painter and poet David Jones, above, one of 109 sketches and two sketchbooks available by the same artist. You’ll find letters like that below, written by sculptor Kenneth Armitage to his wife Joan Moore in 1951—one of hundreds. These are but the tiniest sampling of what is now “but a drop in the ocean,” The Guardian writes, “given the more than 1 million items in the [physical] archive.” Archive head Adrian Glew calls the collection “a national archival treasure” that is also “for the enrichment of the whole world.”

![Letter from Kenneth Armitage to Joan Moore [1951] by Kenneth Armitage 1916-2002](https://cdn8.openculture.com/wp-content/uploads/2014/12/Kenneth-Armitage-Letter.jpg)

Letter from Kenneth Armitage to Joan Moore via the The Kenneth Armitage Foundation

The remainder of the digitized Archives & Access collection—52, 000 items in total—should be available by the summer of 2015. While viewing art and artifacts online is certainly no substitute for seeing them in person, it’s better than never seeing them at all. In any case, millions of pieces are only viewable by curators and specialists and never make their way to gallery floors. But with the appearance and expansion of free online archives like the Tate’s, that situation will shift dramatically, opening up national treasures to independent scholars and ordinary art lovers the world over.

Related Content:

The Metropolitan Museum of Art Puts 400,000 High-Res Images Online & Makes Them Free to Use

The National Gallery Makes 25,000 Images of Artwork Freely Available Online

LA County Museum Makes 20,000 Artistic Images Available for Free Download

Josh Jones is a writer and musician based in Durham, NC. Follow him at @jdmagness